One in a Billion

I will never forget the lights. I remember walking out onto the pitch for the 2010 World Cup Final and being blown away by the flashes of cameras and mobile phones. There were 84,000 people in the stadium in South Africa. Imagine looking up into the night sky and seeing 84,000 flashes all at once. Like a dream.

There was a little girl holding my hand as we walked out of the tunnel. Before every match, a few lucky kids get selected to walk with the players to the pitch. My girl wasn’t rattled by the moment at all. She was all smiles. Me, I was so nervous that she was probably thinking, Why is this guy squeezing my hand so hard?

These kids were from all over the world, about seven years old. As they were playing the anthems, I was thinking about how many little kids grow up kicking the ball, dreaming of starting in a World Cup Final. One time I googled and found out there are two billion children in the world. How many love football? At least a billion, right? I was about to be one of 22 people on earth to get to start the World Cup Final. Why was I so lucky? Even now, the feeling overwhelms me.

I was not an easy kid. It’s just how I am. When I was seven years old, I was running around the house like crazy, probably jumping on the couches, when my mom handed me a sign-up sheet for something called “Ajax Talent Week.” She just wanted to get me out of the house for a while so I could run around and let out some energy.

Ajax is the top football club in the Netherlands. Every year, the club holds a tryout for their youth academy. It’s actually more of an open audition, where more than 1,000 kids show up for the tiny, tiny chance of being selected. You have a few minutes to show the scouts what you can do. You run, dribble, hop around some orange cones and hope to stand out. It started out being all for fun, but then I made the next round. And then the next round, and then the next. I ended up being one of 15 kids selected to the Ajax Academy. My parents aren’t big sports fans. I don’t think my mom understood what was happening. At seven, I don’t think I could even wrap my head around it myself.

For the American readers who are just getting passionate about “soccer,” let me explain how the academy system works. All the top teams in the world — Real Madrid, Bayern Munich, Manchester United — begin recruiting players before the kids start shaving. They bring them up living and breathing the team’s system. Look at Barcelona, which has one of the most legendary academies, La Masia. Half of their starting XI from last season came up through their academy system — Xavi, Iniesta, Busquets, Pique, and Messi.

The Ajax Academy is known as one of the best in the world. Growing up in that type of environment was not easy, especially for a kid like me. I would only go to school for half a day, and then a van would pick me up and bring me to the academy. You’re training constantly, perfecting every part of your body. First just the physical, getting stronger and fitter. Then technique with the ball, especially dribbling. You dribble so much that the ball becomes an extension of your body. Then most important of all, tactics. The famous Ajax system — the 4-3-3 — is beaten into you. Even if you’re only seven or eight, you’re learning this comprehensive philosophy every single day.

Here’s the thing, though: Even if you make the academy, you’re only about 10 percent of the way to your dream.

It’s a punishing life. At the end of every year, you get an evaluation. The trainers and coaches bring you in and talk about your progress, and every year, kids get sent off. You would see these little kids coming out of the room, crying their eyes out. Just like that, the dream was over. At Ajax, that’s the price of greatness. You’re expected to win every game, and you can never come in second. As a young kid, that was tough. It was never about the pleasure of the game. They only expect champions. The coaches would be yelling at you in the locker room, and there would always be kids who would simply break under the pressure.

I was never, ever the best player, always just surviving another year. But then puberty happened. When I was 13, I started rebelling. I didn’t accept criticism from anyone, and starting talking back to the coaches. I acted like a tough guy, saying that I wouldn’t care if they kicked me out of the academy. They called my bluff and sent me home. It probably should’ve been the end. Ajax is not only the best club in Holland but also the only professional club in Amsterdam. So when kids are sent away from the academy as teenagers, many give up and go party (not hard to do in Amsterdam) or try to make up for lost time at school. For me, football was all I wanted to do.

So I swallowed my pride and went to play for a smaller club called Haarlem — an hour bus ride from Amsterdam. Haarlem was much poorer — it actually doesn’t exist anymore because it went bankrupt — and less competitive. It was also a bit looser and more fun. You had to watch yourself around the lads. After training when you’d be dying of thirst, the vets would come up to you with a water bottle and offer you some refreshing lemonade.

Ah man, what could be better than an ice-cold lemonade?

The smart lads could usually tell by the temperature of the bottle what was up. It was yellow, but it was most certainly not lemonade.

Schoolboy pranks. Classic.

It was a bit rough at Haarlem, but I was having fun again. I loved going out there every day and laughing with the boys. At that moment, it was exactly what I needed. The strict professional environment with people shouting at you every day, that was not the way for me. I had to grow more mature as a player and as a person first before I could thrive in that sort of competitive atmosphere.

I started playing really well again, and my behavior got much better. After three years at Haarlem, Ajax wanted me back. Their biggest rival, Feyenoord, also wanted me, and they were willing to give me a contract, which Ajax didn’t want to do. I had to make a choice. I could’ve been stubborn and said, “Forget Ajax. They sent me away, I’m not going back.” But in my heart, I knew they were my club. I decided to go home.

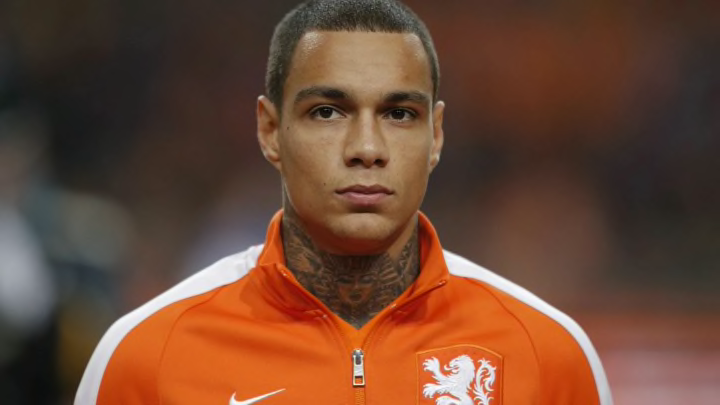

When I returned to the academy at 17, I was a different person. So much so that I was soon named captain. Two years later I was called up to the senior squad. I really thrived as a defender (my mom says I’m still the same skinny little guy who loves to run around) and my performance at Ajax earned me a spot on the Dutch National Team and a place in the starting XI at the 2010 World Cup Final.

But why me?

From the group of guys I started with at Ajax when I was seven, only three of us made it to the professional level. Three of us out of 1,000 kids who showed up for tryouts. I was never the best. Any year. There were so many players who were better than me, but I’m the one who made it. The past five years have been unbelievable. Two Dutch titles with Ajax and then three French titles with Paris Saint-Germain. (That’s a whole other story to share in the future). Just 10 years ago, I was playing in front of 3,000 people at Haarlem and not even thinking I was the best player. Now I’m playing on the world stage with PSG, and I’m still amazed when I’m recognized on the street. When will it stop feeling like a dream?

Whenever I run into little kids, they always ask me, “How do I become a footballer?” I am not sure how to answer that. Do I tell them to train every day? There are million of kids who can run fast and play for an hour. Do I tell them to always listen to the coaches? I didn’t always do this myself. The only honest answer I can give them is to always have fun. I think that’s the secret that gets lost now, with so many parents and coaches putting pressure on kids to perform like professionals at age eight, nine, ten.

So my only genuine advice is to remember that this is supposed to be fun. Oh, and one more thing: Do not pee in your teammate’s water bottle. That’s weak. It’s much more fun to find embarrassing photos of them on the internet and tape them to their locker, like we do at Paris Saint-Germain. Except for Zlatan. There are no embarrassing photos of Zlatan on the internet.