How We Ball in NYC

It all starts with Pearl Washington.

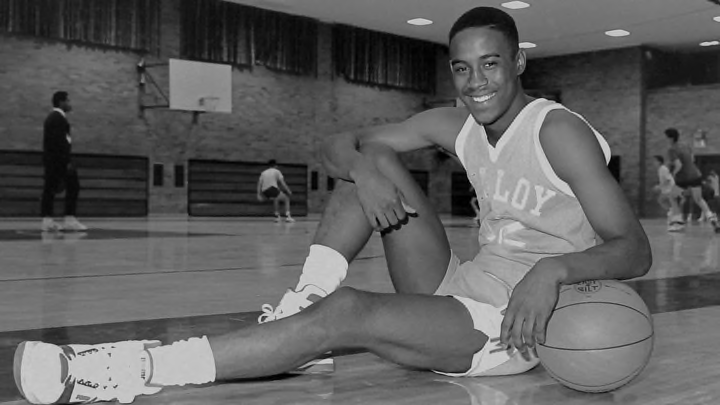

If you ask me, Pearl was the guy who really perfected the whole New York City-basketball-with-attitude image we think of nowadays when we talk about great players from New York. And he was also the one who made the New York City Point Guard — with uppercase letters — a thing. Pearl may not have been the original model — Bob Cousy, Lenny Wilkens, Tiny Archibald and a bunch of other guys preceded him — but he locked down the brand. He’s the archetype.

Growing up in the 1980s, everyone I knew who played ball in NYC wanted to be Pearl Washington.

I did, too. But more than anything else, I wanted to have his swag.

Pearl wasn’t the best shooter, and he wasn’t going to dunk on you or anything like that, but let me tell you: He was a baaaad man. His craftiness on the court, his passing ability, his ballhandling skills, they were all exceptional. When I watched tapes of him playing up at Syracuse, though, what stood out most was that Pearl carried himself differently than every other player on the court.

There was this cockiness — or arrogance, or whatever you want to call it — to how he played the game. It was always like: Nobody’s stealing this ball from me. I’m about to do these cats. It’s about to be on. But the thing is, he didn’t verbalize any of that stuff. He said all of it, and more, with his body language — with the subtle tilt of his head, or a raised eyebrow, or even with the way he would lift his arm to call out a play after crossing half-court.

Pearl was the guy — an embodiment of New York City on the basketball court. And he gave players like me, who followed after him, the blueprint.

By watching Pearl, we learned how to beat an opponent before he even stepped on the court. I mean, some dude from the middle of Arkansas, or from some small town, who hadn’t run into guys like us — walkin’ tall and talkin’ and just being real confident — that dude didn’t stand a chance. He’d be like, Wow, this kid must be gooood. And right there, he was dead in the water. Done. It was over.

Pearl showed us how to do that. He gave us that. He taught me and the guys from my generation how to be New York City ballers. It was like a gift, and you better damn sure believe that we ran with it.

***

In New York City, we eat, sleep and breathe basketball.

It’s not like that everywhere. Places like L.A. or Detroit or Atlanta, they have some nice players. But they don’t eat, sleep and breathe basketball. They might say they do. But it’s different where I come from.

New York is the mecca. We hoop at the playgrounds from sunup to sundown.

And it’s serious.

I mean, I played at Rucker Park in 1983 when I was 13 years old. And even at that age, I schooled people. It was either that or get called a punk and be laughed off the court. Basketball heads in New York don’t care if you’re a kid — it’s strictly show and prove, no matter how old you are. So you either get good fast, or you do something else.

Since I didn’t want to do something else, my summers were all about basketball. I played AAU ball for Riverside Church up in Harlem, and then for the New York Gauchos. It would be three or four games every day. And in the ’80s, you sometimes had to be creative to get to a court. I lived in the LeFrak City projects in Queens, but our games were all over the city — in all five boroughs. Even though our teams usually had a van, if guys couldn’t fit in the ride — or if you got to the meeting spot too late — you’d have to jump on the train and meet up with the team at the court. We’d be hustlin’ from Queens into Manhattan, then over to Brooklyn, then back into Manhattan, or out to Long Island, all in the same day. It was crazy.

And back then, I didn’t have any money. None of us did, really. So we’d have to jump the subway turnstiles. Or we’d use one token and squeeze two guys through. A few times we got caught, and I had to plead with the cops. I’d be like, “Listen, man, we’re trying to play ball. We’re not criminals. We’re just some broke-ass kids trying to get to a game.” They’d give us the business, but eventually they’d let us go. They understood.

Of course, once we got to the spot, there would be other challenges. Most of the time, we were playing on blacktop asphalt, and it wasn’t always pretty. For starters, summers in New York City are hot! So you had to be careful about all sorts of things — dehydration, heat stroke and some other weird problems you’d never imagine. For instance, when I was growing up, Chuck Taylors were really popular, and those shoes don’t have much cushioning to them. Since they have these flimsy rubber soles, my feet would be burnin’ up because the tar on the blacktops got so hot. Some days, I had to wear two or three pairs of socks just to keep my feet from frying. So it’s 100° out, and I’m doubling up on socks.

And before the games, sometimes you’d have to sweep off the court because there’d be broken glass everywhere. The night before — late night, 2 or 3 in the morning — you’d have people selling drugs or fighting or doing all sorts of things on those courts, and then our games would start at 8 or 9 a.m.

It was real grimy.

When the games started, you’d be getting thrown down. You’d be getting tripped up. No fouls called. And if you called a foul, everyone on the other team was calling you soft. You were arguing, you might be fighting on the court. In New York City, basketball is a contact sport.

After enough of that, you couldn’t help but build up a certain toughness. And if you were a point guard, like me, you’d also gradually cultivate a level of showmanship. Here again, you didn’t have much choice.

You needed to wow people and make heads turn, or risk getting laughed out of the park. It wasn’t enough to be able to get up and down the court in the blink of an eye, you’d have to impress people with how you did it. As a New York City point guard, accumulating oohs and aahs was imperative. It would be all about crossing dudes over, or going behind your back, or between the other player’s legs, or firing a no-look pass from half-court, or throwing up an alley-oop behind your neck and having someone dunk it — all that stuff was like currency for a point guard in the city.

And this wasn’t just in the summer, either. It was all year round. Basketball in New York City never stops. We’d be out there in the park with hoodies on. If it rained, we’d play through it. If it got too wet, we’d take it to a gym. But wherever we could play, we’d play — the conditions didn’t really matter.

A lot of people from other cities don’t realize that New York courts are all different sizes. Some gyms are really small, some have low ceilings, others have almost no space between the baseline and the gym wall.

Even some outdoor courts are the wrong size. One of the most famous courts in the city is West 4th Street in the Village, “The Cage.” That place is tiny! As soon as you turn around after a rebound, you’re at half-court. I hated playing there because there wasn’t any room to move, so it always got super physical. I’m not soft or nothin’, but you could really get hurt out there on a small court.

Fights were more common at West 4th, but they happened everywhere. I was pretty lucky coming up, because guys never really bothered me too much.

Actually, let me put that another way. I wasn’t “lucky.” I had people — big, strong people — who took care of me and made sure that no one messed with me on or off the court.

When I was a teenager playing ball in New York, you had to be badass if you wanted to go to other boroughs and play. If you lived in Queens, and were just a guy, you couldn’t really just go to Manhattan or to Brooklyn or to Long Island and play in different neighborhoods, because you could get yourself into a ton of beef. Everyone who played ball in the city knew that. I mean, you might show up, and they’d have you runnin’ out of the neighborhood.

So you had to stay in your own ’hood unless you were that guy — someone who had made a name for himself.

But, even then, it could still get dicey. When I was coming up and everyone throughout the city knew who I was, I still had to bring my buddies with me to games in other boroughs. If people tried to start some mess with me, I always had backup around — I called them my enforcers. These were guys who had gotten into a little bit of trouble and were more into the street life. But I knew them from way back, and we were cool. Those dudes didn’t play around. They were scary, and they would do anything for me. No questions asked.

I mean, that’s about as New York as it gets right there.

***

Pearl Washington may have perfected the New York City Point Guard persona, but he didn’t have a trademark on New York swag.

In fact, there was a whole lineage of point guards I looked up to when I was putting in my time on playgrounds throughout the city. Kenny Smith, Mark Jackson, Boo Harvey, Kenny Patterson, Rod Strickland, Kenny Hutchinson, all those guys came before me and were making noise when I was a kid.

I looked up to all those dudes, and I tried to incorporate the best parts of each of their games into how I played.

Kenny Smith, for instance, was a wonderful mentor to me. He taught me so much about basketball as a kid, and I always paid close attention when Kenny was on the court. He was a great shooter, but what made him exceptional is that he could jump out of the gymnasium — he could really sky. Kenny was dunker, and back then, at the point guard position, no one was really dunking like that. I mean a point guard, with jets, who was dunking on people? It was a sight to see.

Now, Mark Jackson, he was unique in a different way. He was bigger than most point guards, and he used his body really well, but his vision was off the charts. He passed the hell out of the ball. I would always watch him and pay attention to his passing. And, of course, Mark had a huge amount of New York City swagger, which I loved.

All of the best guys during that era — Mark, Kenny, Boo, Chris Mullin, all of them — had a certain flair, a supreme level of swag, that made them special. They were New York through and through, and it was unmistakable. I loved watching those guys do their thing in the ’80s and rep for our city.

The funny thing, though, is that the player I actually modeled my game after the most, Nate Archibald, was someone who came before all those guys and was crossing people over when I was still in diapers. Some people called him “Tiny,” but in New York we knew him as “Skate” — Nate the Skate. That was my idol, right there. He’s a guy from the South Bronx, DeWitt Clinton High School, who became a playground legend. Nate was a star in the NBA by the time I was coming up, and because he was so quick to the hoop, and right around my size, and left-handed like me, I tried to play just like him.

It was a high bar, of course, but I did my best to follow Nate’s lead. And it worked out pretty well for me.

After I went on to Georgia Tech and got drafted by the Nets in ’91, the point guard scene in New York started to really heat up again, and the most talented player to rise up during that era was Stephon Marbury from out in Coney Island, Brooklyn. That guy could shoot, he could handle the ball, he could jump, and he was super explosive. He had it all. And, for me, the really cool thing was that Stephon, as a youngster, was kind of like I was with Nate.

He modeled much of his game after mine, and one of the main reasons why he wanted to go to Georgia Tech was because I went there.

Stephon looked up to me, and he’s been so kind and open in acknowledging that throughout the years. He’s always been quick to tell me what I meant to him and how much I did for him. That’s been really special for me.

Back in the day, he even went so far as to copy my hairstyle — I used to wear a part in the middle of my hair, and then a little while later Stephon started doing it. When you look back at all his high school pictures, he’s got that part down the middle of his head. And I remember him telling me that when he was in high school, he and God Shammgod used to battle on the court to see who would be crowned Kenny Anderson. They’d fight it out, and the winner got to claim the title of being KA.

Can you imagine?

That kind of stuff, thinking back, really makes me proud. I mean, it was cool at the time, and I appreciated it. But now that I’m a little older, it’s really touching.

Memories like those remind me of how fortunate I am to be part of such a special group of individuals who rose up from the playgrounds of New York City to take the basketball world by storm. New York made each of us the players that we were. In return, we showed our gratitude by playing with passion, toughness and style each time we stepped on the court.

And every time we did, there was absolutely no mistaking where we were from.

*

Kenny is currently working on a feature-length documentary titled Mr. Chibbs, which explores his life both on and off the court. You can check out the film’s website and help support it by visiting its Kickstarter page.