The Fight of Our Lives

I’m a racecar driver, so it goes with the territory that I do things fast. But as with anything in life, speed isn’t always a good thing. There are moments when you’d do whatever it takes just to slow the world down and stop time.

When I’m on the track, that’s the good fast. The fast that you sort of feel coursing through and that pushes you to punch it harder — to really see how fast you can fly. I used to think you couldn’t feel speed like that anywhere else.

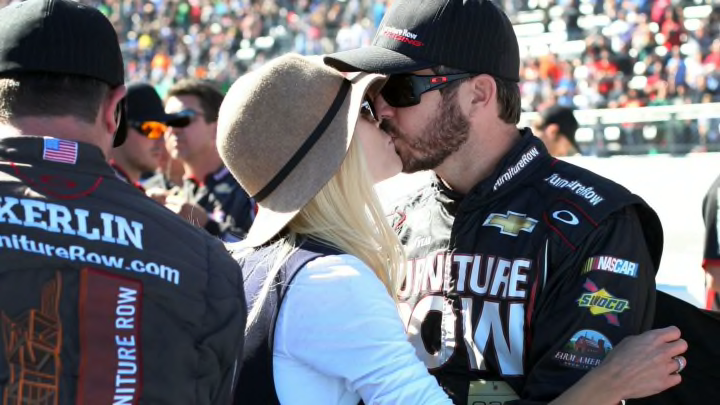

But when I met Sherry, well, that was the best fast. The fast where you can’t think about anything else.

We were first introduced at a racetrack (of course) over 10 years ago. Just a quick one-minute introduction during some dinner — she was buddies with my PR guy and she worked PR for another race team. I didn’t think much about it, until I saw Sherry again during a night out with a few friends, and we just hit it off.

I was totally into her, and at that moment, all I could think was, How can I make this girl like me?

I must have done something right, because from then on, we were doing everything together. With Sherry, it was just easy. Being with her was one of those things where you were all-in right from the start. You never really questioned it, you never really thought about it. You just did it because it felt right. We’d only been out a few times, and I remember thinking, What the heck’s going on here? Why is she all I can think about?

We spent as much time as possible with one another, and no more than six months later, we moved in together

The best fast.

And then there are the not-so-great fasts. The kind of fast that wallops you from nowhere and knocks the air out of your chest.

One of those moments came on Thursday, August 7th, 2014. It was an off day in the midst of the worst season of my NASCAR Sprint Cup Series career. When Sherry’s doctor asked me and our families to come to the hospital immediately, we knew something wasn’t right.

Sherry had gone in that day for a CT scan at our local hospital because she hadn’t been feeling well for months. For some reason, no one could diagnose what was causing the severe pain in her abdomen. She was caught up in the proverbial game of “patient pinball” — being bounced around from doctor to doctor with no definitive diagnosis.

Thirty minutes later, I got that call from the gastro surgeon telling me to come to the hospital. We thought she had gallbladder stones or an obstruction in her stomach that would require simple surgery. Sherry previously had ovarian cysts, and one had ruptured. But the OB-GYN wasn’t that concerned about it and didn’t try to diagnose the problem — not her fault, she was simply following normal protocol based on her symptoms.

So when Sherry’s mom, myself and one of our good family friends arrived, we all met with the doctor immediately. When we entered his office, it was obvious he was concerned.

Just a few seconds passed — no time at all — before hearing two words that changed our lives.

Ovarian cancer.

Hearing the word “cancer” catapults you to a place of hurt, sadness, despair and the unthinkable: mortality. I often tell people that it’s the club you never want to be a part of, and it seemed like our membership was fast-tracked for admission. Within the seconds it took for six syllables to land in the air, life would never be the same for Sherry and me.

From that moment on, my world went into a tailspin. I remember hearing Sherry’s mom crying, but, Sherry, typically, asked the doctor what the next steps were. Sherry grew up on the track and her father owned a racing team, so she was ready to move fast, too — and fight. Upset, but not crying, Sherry looked at the doctor and said, “How are we going to beat this, and what are my options?”

Sherry’s doctor explained that the cancer had spread throughout her pelvic area and abdomen. We were set up with an appointment to meet with a gynecological oncologist the following day. Surgery and treatment were not optional at this point — they were lifesaving. The reality was, if we didn’t get her help as soon as possible, her Stage 3 diagnosis would become worse.

It was time for us to move fast again.

Meanwhile, I’d been struggling on the track. I was 24th in points, the lowest in my career. It seemed like everything was falling around us. Sherry was diagnosed on Thursday, and I had NASCAR Sprint Cup practice the following day at Watkins Glen in New York. Practice was truly the last thing on my mind. I didn’t want to leave her. I couldn’t bear the thought of getting on that plane the next morning without her. Throughout my career, Sherry has always been at my side. Good or bad days on the track, Sherry is my biggest supporter.

Race days for us are really routine. We get up and I’ll usually have some meet-and-greets and appearances to do. Then we just sit in the trailer, hanging out and relaxing with our charcoal lab, Boden. It may seem simple and not so special, but those moments get me relaxed and ease my worries before a race.

But now it was my turn to be Sherry’s support system.

When we got home from the hospital that day, she fell into my arms, sobbing, “Why me?” As I held her in my arms, I couldn’t help but think the same thing. Sherry has always been kind and caring. We’d been working the last 10 years on support and research for pediatric cancer through building the Martin Truex Jr. Foundation. NASCAR is involved with a lot of charitable organizations, and through our work, we met a lot of children and families at the racetrack who were dealing with cancer. We decided to focus on that cause because we’d both had great childhoods — our families took good care of us and we never had to worry about anything. So when felt like it was good time for us to use what we had to help people, we were pulled in immediately.

When you first meet with these families, you’re sympathetic to what they’re going through, but you don’t really understand. But once it happens to you or your loved one — and you never think it will — there are no words to describe the heartache and fear that comes with the diagnosis.

I made the decision to return to the track the next day. After a long discussion with Sherry, her family and my business manager, we all agreed that I needed to go to practice. If I didn’t, the media would notice and my team would want to know why I wasn’t there. I’d been racing in this NASCAR Series for nine seasons, and I’d never missed a practice or a race. We just weren’t prepared to address the media about Sherry’s condition, and I knew it would be a huge distraction for both myself and the race team. So reluctantly, I headed to New York the next morning while Sherry remained in Charlotte with family to meet with her oncologist.

The following week was a whirlwind of doctors appointments and tests to determine the exact location of Sherry’s cancer and to schedule surgery. The surgery was performed on August 15, just a short week after we first heard those words. We arrived at the hospital at 5:30 a.m., and Sherry was prepped for what we thought was going to be a four-hour procedure. Instead, after seven hours of surgery, which included a radical hysterectomy and the removal of tumors all the way up to her spleen and appendix, the doctor was finally confident that he had removed all “visible” signs of cancer. It was only four months from the time Sherry had initially told me she was having abdominal pain, and the cancer had literally spread everywhere.

The next week was difficult, I didn’t want to leave Sherry at the hospital, but I had to get back in the racecar. My car owner, Barner Visser, offered to let me sit out the rest of the season and take care of Sherry. But Sherry and I never considered it.

We both needed to get back to our normal. And normal for us is racing.

I flew back and forth every day after practice, which was in Michigan that weekend, to our home in Charlotte to be with Sherry. After eight days in the hospital, Sherry came home. They gave her a three-week break to regain her strength before starting chemotherapy treatments.

No one can prepare you for chemotherapy or what it does to your body. Watching Sherry go through the grueling eight-hour chemotherapy sessions every couple of weeks for six months was almost unbearable. She lost her hair and lost 27 pounds from her healthy weight of 120 pounds. She could barely walk from the living room to the kitchen in our home. It was one of the darkest times in our lives. Sherry opted to do additional chemotherapy, once a month for a year, to prevent the cancer from returning. Ovarian cancer tends to respond well to chemotherapy initially, but it can return within a two-year time period. Her disease also has an 80-percent recurrence rate when diagnosed at Stage 3. So we knew we had to do whatever it took to keep this disease away for as long as possible, and we agreed that the monthly treatments were the best option.

These may seem like grim details to share, but for Sherry and I, raising awareness of what she went through is the most important thing we can do now.

Ovarian cancer is a complex and difficult type of cancer. The symptoms are vague and often mimic other illnesses or conditions that women commonly experience. That’s why ovarian cancer is so difficult to diagnose. Most women go to their doctors repeatedly and explain their symptoms, only to be misdiagnosed, just as Sherry was. What sticks out in my mind from our experience is that when the doctors first told us Sherry had ovarian cancer, we didn’t know anything about it. Both of us were like, “What is that? What does that mean? How could nobody tell us three months ago?” There’s not a lot of information out there for either women or doctors, and there needs to be a better understanding for what it is and what the symptoms are. There’s now also a simple test, OVA1, that provides doctors with earlier guidance on how to proceed with surgery

Our race days were never big or flashy, but not having Sherry there those months she was getting treatment was really difficult. Just sitting in the motor home didn’t feel right without her being there. I talked to her before every race, and I knew that she wanted me to be there, which eased my worries a little bit. And when I put my helmet on, everything else leaves my mind and I’m able to focus on what I need to do. But those times sitting around thinking by myself were definitely hard.

Sherry recently finished her chemotherapy treatment a couple of weeks ago, and it feels to me as if completing those 17 months of chemotherapy is the biggest accomplishment of both our lives. It’s great to see her doing the things she loves again and getting back to normal life. Having Sherry there by my side in Victory Lane for my win at Pocono — my first in three years — and at Homestead for the final race for the Championship was awesome.

Now we’re getting ready to head to Daytona to start the 2016 NASCAR season. I’m coming off my best-career finish ever, coming in fourth in the points standings for the 2015 season. I competed as one of four contenders for the NASCAR Sprint Cup Series Championship. This season, Sherry will be back traveling full-time with me (and like always, so will Boden).

Even more importantly, the MTJ Foundation rebranded to focus on both pediatric and ovarian cancer. We hope our funding and advocacy can provide much-needed resources while raising awareness about this terrible disease.

Since the Foundation started, we’ve been committed to helping children beat cancer. With the addition of ovarian cancer, we are raising awareness and asking women to be their own health advocates — to listen to their bodies and understand the symptoms of a pelvic mass and its relation to ovarian cancer. I never thought I would get a crash course in women’s anatomy and use my time in NASCAR talking about my girlfriend’s ovaries, but that’s life, and it’s what we’re doing. Honestly, there’s no way to really understand what cancer can do to someone or to a family unless you’ve lived through it and seen it firsthand.

So for us now, it’s personal. It’s changed our perspective and our understanding of what these people are going through, and it makes us want to work even harder. We hope to empower women with knowledge so they don’t have to suffer through painful surgery and chemotherapy treatments the way Sherry did. The Foundation will also provide resources for helping with medical bills and funding for improved and less-toxic treatment options.

We’ve only just begun this journey of educating men and women about the symptoms of this disease. Our goal is to change the way this disease is diagnosed. After everything we’ve gone through, we look at everything a lot differently now, and certainly racing is one of those things. When I drive through that tunnel at Daytona this week, I’ll think about Sherry. I’ll think about the good days and not take them for granted. But now I also know what to think about when the bad days come around.

Go fast and fight like hell.

For more information about the Martin Truex Jr Foundation and their work with pediatric and ovarian cancer, visit www.martintruexjrfoundation.org