The Game

The game comes with a lot of pressure. That’s a given. That’s expected. That’s known.

That’s the game.

But for as many teams and guys that you play against, you always have the narrow view that what you’re going through is more difficult than what they’re going through. Your problems are what matter. You’re the one feeling the most pressure.

Coming into the 1994 World Cup, I was completely focused on what my team had to do, what my role was. Everything else was on mute.

But that changed the day before our second game of the group stage, against Colombia. We had just tied against Switzerland 1–1 on June 18 in Detroit. Colombia, meanwhile, was coming off a 3–1 upset loss to Romania — a result that nobody had expected. Sitting down with our team in our L.A. hotel when I opened up a Spanish-language newspaper. One of the reporters covering the tournament had left it behind. I had a pretty decent grasp of Spanish, so I could more or less make my way through the stories about the Colombian team. But then I skimmed over a few lines that couldn’t have meant what I thought they did.

I called over my teammate, Tab Ramos, who had been born in Uruguay and spoke Spanish fluently, to help translate.

Amenazas de muerte y secuestros.

“Death threats and kidnappings,” he told me.

Wait, what? Death threats and kidnappings aren’t exactly things you expect to read about in soccer coverage. But there they were, in black and white. In that moment, my eyes opened to what was going on in our opponent’s home country.

That was when I knew there was more being attached to these games to these games than just winning and losing. Quite often, people talk about soccer as if it were a matter of life and death. It’s usually a metaphor. But for these players, this tournament really was a matter of life and death.

For us as Americans, it couldn’t have been more different.

From the start, we were excited, having fun. We knew the home fans — 1994 was the first time that the U.S. had ever hosted the World Cup — were going to cheer for us. But how could we get them to really believe in us? That was our biggest challenge. We wanted to help grow the game on our home soil.

And yeah, we had a chip on our shoulder. We wanted to prove that we could compete against the best. Looking at our group: Switzerland, Romania and Colombia, we thought that just maybe there was a situation where we could finish with four points and advance to the knockout stage. But we needed to get a result. Maybe we can get a win against Switzerland. Maybe we could go head-to-head with Romania. But Colombia? That was going to be hard — they were one of the favorites to win the whole thing.

The night before Switzerland, I just had to get focused. We had landed in Detroit a couple days earlier, as they were rolling out sod and natural grass — yes, grass — over the artificial turf in the Silverdome. Not the best surface, it was pretty slippery and only added to our anxiety. I had been playing professionally in England (first for Sheffield Wednesday and then for Derby County), and I had a turn-everything-off approach, which kind of conflicted with the approach of my roommate, goalkeeper Tony Meola, who wanted to put the TV on and zone out and help him fall asleep. Which I was O.K. with, except that night, of all nights — the night before our very first World Cup match — O.J. was on the run in the white Ford Bronco. Tony was glued.

“Tony. Dude. Turn. It. Off.”

We watched for a bit, then managed to shut it down.

When we got to the dome the next day, the fans were in red, white and blue — faces painted, signs everywhere, wearing jerseys. Full out. The only problem was, it was a cauldron inside. They were trying to get the air conditioning going, but the circulation was really poor. It was so humid. The heat was suffocating the entire time, but we fought through it and got the draw. Our first World Cup point. And we thought, We’ll take it.

As we were grabbing some food in the locker room after the game, our media guys started getting word of the other match in our group, Colombia vs. Romania, which was being played at the same time as ours.

“Fellas, Colombia lost 3–1.”

“What? Did somebody get that score right? Check it again.”

“3–1.”

Holy. Shit. The door just opened for us. We had an opportunity. On the plane to Los Angeles, I sat with Earnie Stewart, Tab and Tony and we started running through plans. Tab, being from Uruguay, knew quite a bit about Colombia’s background, their characteristics, their many strengths, their lack of weaknesses. So we were just going through everything how they could have lost their opener and conceded three goals.

At our DoubleTree hotel, the strategizing continued. How could we shut them down? Would they continue to build out of the back? What was the mentality of their goalkeeper right now? What mistakes did he make in the first game? Colombia was a great passing team, very organized, and it’s players were very skilled. So how were we going to compete against that? Tactically, how were we going to work things out? Coach Bora would address all that, but our mentality and approach had to be right. The focus to defend properly as a collective had to be sharp.

And then, I picked up that newspaper.

When I looked back at Tab after he said those words — death threats, kidnappings — I saw that his face showed none of the disbelief that I felt. Neither did Hugo Pérez, Marcelo Balboa or Fernando Clavijo, guys who had ties to Central and South America.

“This has been going on for awhile,” Tab said.

It’s not like me and the other guys were totally ignorant to world issues. But the guys on the team who had been born and raised in the U.S. were all taken aback. There was a real pressure on Colombia and it threw us. I mean, Colombia went through qualifications and they killed it. They were destroying teams. They beat Argentina twice by a combined score of 7–1. They scored 13 goals and only allowed two while winning four of their six games. Everyone. All of a sudden, there were high expectations. Stories start flying off the handle, drug cartels are gambling, there’s going to be deaths if they don’t win, there’s going to be all this pressure on the players.

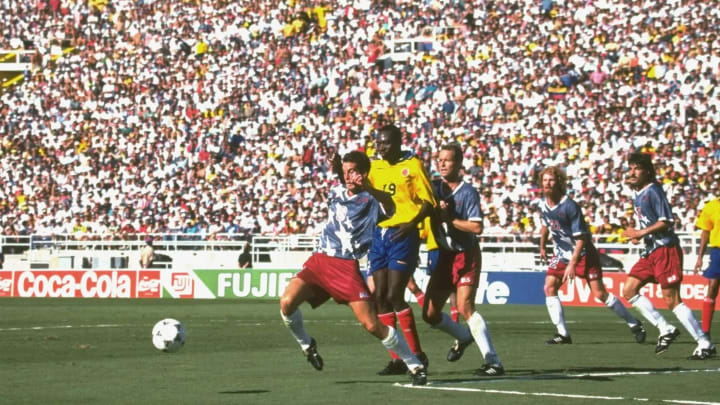

When we got to the Rose Bowl on June 22, it was everything the Silverdome hadn’t been. It was outdoors, obviously, and that alone brought this different feeling. There was tailgating — it was a hot, beautiful day. It was a huge celebration from the minute we stepped onto the pitch for warmups. And as we lined up, our national anthem played. Then Colombia’s started. And as much as I wanted to focus on the game in that moment, the human instinct took over. I was concerned. I cared about them because I knew that, just like me, they were athletes, and they were just there to play the game that they loved.

But at the same time, we’ve come here to play, compete and represent our country, too. We’ve got to do our job.

That’s the game, you tell yourself.

The whistle blows … there’s a roar … and once you kick the ball for the first time, it’s just you and the game. It’s you and the ball. And the ball doesn’t know your age, doesn’t know the pressure on you, doesn’t know your pressures in life It is a ball, and you must give the ball energy and control it to the best of your ability.

That’s all you can concentrate on.

You’re completely free, wide open. Anything is possible.

Colombia exploded out of the gate. They pressured us. Their speed and ball movement were on fire. And our only way to weather that storm was to fight and chase and squeeze and try to slow the game down. Marcelo cleared a ball off the goal line. Tony was getting pelted with shots. Lexi, Clavijo, and Calaguri were all working hard, diving and trying to block shots. We were all doing our part.

And then about 30 minutes in, the ball got switched out to me from Mike Sorber. I was running down the wing and my first instinct — from playing with my English clubs — was, Can I stretch the team out wide? Can I be positive and run at them? Can I get an early cross to Earnie? I saw him zipping into the box with an unbelievable run toward the back post. I hit it across as hard as I could.

I saw Colombia’s Andrés Escobar stretch his leg out to block it …

… the ball deflected hard …

… and it slowly trickled across the goal line.

It all happened so fast. When the ball left my foot, it was a matter of split seconds before Andrés redirected it. It was instantaneous. It was a goal. And I just immediately turned to our bench to celebrate. It was an own goal, it wasn’t like we scored it, but we created it, we put enough pressure on them to force them into that situation. So yeah, we celebrated. We’re 1–0 up. Against Colombia. In the World Cup.

Swarming in a huddle, we couldn’t see the reaction from the Colombian players. Of course, watching on the TV later, there’s the shot of Andrés on the ground, his face in his hands. Once we started jogging back to the circle, my thoughts are just, Focus, focus, focus. And then I turned and saw how how shocked they were. But that didn’t stop them. They continued to force the action. When I look back on it, I think about how that took an unbelievable amount of character. People thought they were poor team, having a disaster game — knowing nothing about what they were going through.

We put the ball in the net again in the second half. But even up until the 90th minute, Colombia kept going. They scored a goal. I remember being beside Carlos Valderrama in midfield, and he just has this look on his face. Stone cold determination.

And then the final whistle blew.

Our fans were throwing American flags onto the field. I went to get water near the bench. I looked across, and I could see Alvarez and some of the other Colombian players walking off with their heads down. You could see the anguish, the stress. You see that in every game, but I think after everything we had read, we just understood.

Four days later, we lost to Romania 1–0. But it didn’t matter. We had made it through our group. Colombia beat Switzerland 2–0, but was still going home.

That’s the game, you tell yourself.

On July 3, we arrived to training. We were playing Brazil in Palo Alto the next day, and as usual, there was a group of media ready to talk to us as we were heading out to practice. Before we took the pitch, a couple of people came up to me.

“You hear there’s been a shooting in Colombia? Escobar’s dead. He was shot.”

I just lost all color in my face. I went numb. I couldn’t fathom it. I couldn’t wrap my head around it. This man, against whom we had played only a couple of weeks before, had been shot dead in his own country. In Colombia, he was respected at the highest level, regarded as a gentleman of the game, a peacemaker, a good man both on and off the field. And he had been killed?

We played a sport. We loved a game. This wasn’t how it should be.

I just felt complete sadness. Your first thoughts go out to his family. The day itself became a blur, maybe it’s because you try to push it away, you don’t want to hear about it. And in the hotel that night, you try to just think about the game. But you can’t. You try to find answers. But you can’t.

And the next day. We still had to face Brazil. It’s the game, you tell yourself.

We lost, we were out of the tournament, and eventually the news started settling in. The questions came up. How do you feel about that? You were the one who crossed the ball. And I thought, Well, that’s just unfair. It was a moment in the game. I struck the ball. A cross. A kick. A deflection. It’s the game, you tell yourself. Teammates tell you not to blame yourself. It’s the game, they tell you.

But the truth is, you do feel connected to it, right or wrong.

And I’ve felt connected to it ever since. I’m thoughtful of the moment. Not as the cause of his death, but for better or worse, that experience changed me. It changed the way I viewed my career, it changed the way, quite honestly, that I viewed life. When I went to the 1994 World Cup, I was 27-year-old guy. What did I know? What was I aware of in the world?

When I first heard about Andrés’s death, I thought about the 1989 Hillsborough disaster,. Ninety-six people were crushed and died at a match held at Sheffield Wednesday’s stadium. I arrived at the club a year after that tragedy and had spoken to a lot of people about that day and what it meant. I didn’t really understand it then — the horrific nightmare they went through. The shock, the sadness, all those lives, all those families.

You never should go to a game and lose your life because of it.

What I take away from both Hillsborough and Andrés’s death is that it’s O.K. to talk about it. We need to talk about it. We need to remember the 96 who died at Hillsborough. We need to remember Andrés. Who they were as people. For me, after ’94, I began to look at the game with a wider perspective of things in the world. As athletes, we’re a small part of a bigger picture.

There’s so much more to the game than just the game, I tell myself.