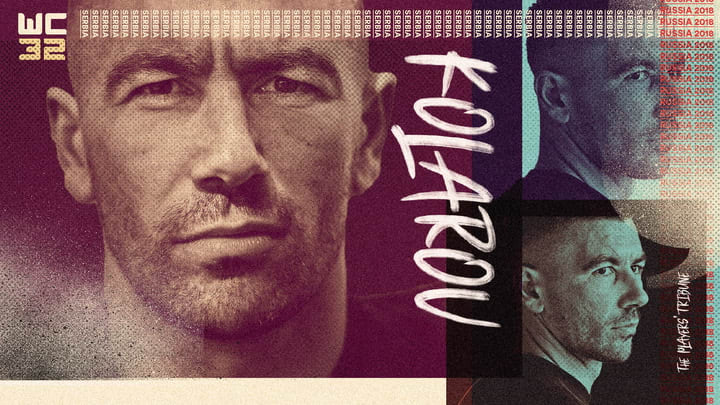

The Nights the Earth Would Shake

There’s a specific noise … I can still hear it today if I close my eyes. It wasn’t the air sirens we were used to hearing. It was different — a whine. More like something from a movie. Somehow, it sounded terrifying. My friends and I turned our bikes around and started riding back home really fast.

We were just a few blocks from our street when we heard a new noise, a big explosion, and we looked up into the sky … and saw the plane falling to the earth.

There was fire coming out of it. And black smoke. It passed through the clouds, then behind the trees, and then it was gone.

It was a military plane, shot down over Belgrade, not far from my home.

This was life in Serbia in the late ’90s.

I got home and sat in my room for a few hours, trying to comprehend what I had just seen. The war hadn’t been going on for long. When it started, actually, I was happy — because I didn’t understand at all. All I knew was that school was cancelled. I could spend more time with my friends or with a soccer ball at my feet.

I remember the night that the first bombs fell. I was 14. My brother, Nikola, and I were sitting with my mom in the living room. She was watching this Spanish soap opera — she never missed an episode. We had just the one TV, so we sat there with her, in silence, confused as to what we were watching. Then the gate outside our front door began to shake. Again, and again, and again. I had no idea what was happening. Later that night we heard on TV what was going on: Belgrade was being bombed.

We didn’t leave our home for the first two days. We tried to sleep through the echoes of explosions from a few miles away, the whizzing of planes overhead, the nightmares. I just remember a great deal of confusion around the whole situation, probably because I was so young. But nobody knew exactly what to do in our town. It was a small place in Vojvodina, everyone knew everyone. As time went on, the shops reopened and we tried to move on with our everyday lives. I mean, what else were we going to do? But it was just … strange. I missed school. I had too much free time, which I never thought I would say.

My dad was a shop assistant, and my mother worked for a small local company — so my brother and I had the house to ourselves. We spent our days in the yard, with a ball and our wooden gate — it was our net. It was a little flimsy, but there was this part … right in the upper-left corner, where if you could hit the ball there it would make this huge noise. That was hilarious to us, because if you really banged it, the neighbours would yell out the window, “Those damn kids are kicking the ball again!”

Every time I lined up a free kick, my goal was to get my neighbours to lean over the fence and yell at me.

That’s how I knew I really hit it well.

So over and over again … big run-up, left foot, nice, dipping free kick. Bang.

I wanted to be Siniša Mihajlović. He could bang them. He played in the midfield for Red Star, the big club in Belgrade. They were … legends — beyond legends. They won the European Cup, right before it became the Champions League, in 1991. I was just six years old, but that was such a huge moment for the sport in our part of the world. At the time, there was already a lot of political turmoil and confusion, and being in our city … it wasn’t easy. And to see that, in the biggest club tournament in the world, players like us, who grew up like we did, could have success — it was massive.

As my brother and I grew up, and as the war became a bigger part of our lives, we understood football was an opportunity we could not waste. We pushed each other, we battled. I was competitive, maybe too competitive. I remember one day we were home alone and we were arguing about who was stronger, like boys do. So we proposed this idea: We’ll each run from one side of the room, jump in the air — like we were going for a header — and see who knocks who over.

I mean, when I say it out loud now … it sounds dumb. But we were just teenagers! It was a rite of passage.

So we lined up on opposite sides of the room, like in one of those old John Wayne movies or something. Twelve paces! Then we ran at each other … and I just destroyed him. He went flying through the air, and as soon as he hit the ground he started yelling …

“Call Dad! Call Dad!”

“You’re fine, get up.”

“CALL DAD!”

Dad showed up, and we lied of course. We told him that Nikola just fell down. That didn’t work. My dad took him to the hospital and it turned out he had broken his collarbone.

It was interesting trying to explain to the nurses how it happened.

Those were the battles that made me tough.

In football, I just wanted to get better and better and better. I think, seeing what was possible in 1991 with Red Star, seeing my country falling into despair … I just wanted more. That desire never left me.

When I was playing with Čukarički in 2004, another team in Belgrade, there was one moment that I still think about today. I was playing with their junior team in Holland and we had this big, unexpected win. Right after, they promoted me and five other players up to the senior side during their push for promotion At our first training session, the team already had 23 players, so the coach wasn’t happy about having us as extras, so he made us run.

He said, “Go do five laps in the forest. Don’t come back until you’re done.”

These were long laps. I remember how hot it was, how tired we all were. After four laps, one of the guys suggested we just stop where we were, because nobody was even watching us. The others agreed, but I couldn’t understand doing that. I hadn’t come this far to not follow instructions. So I ran the last lap as hard as I could. I finished without anyone seeing. I almost fainted. I didn’t run that fifth lap to impress my teammates, or a coach — it was for me. That’s who I am.

If they ever make a movie about me, include that scene, please.

I moved to Lazio a few years later, in 2007. That was the first time I was able to support my family financially, which meant the world to me. I didn’t think of the transfer as a great success, or anything like that, I really just thought I was getting started. I had to fight my way from being a substitute to earning a big role with the team. I learned a lot in Rome and my time there coincided with call-ups to the National team. But I remembered a promise I had made to my mom when I was 12 years old. I told her then that one day I wanted to play in the Premier League in England. And I knew, no matter what, one day I would get there.

The opportunity came from Manchester. City were building something great, and the Premier League was a top, top league at the time. And more than anything, it was an opportunity to get better. That summer, before I agreed to move to Manchester, I played with Serbia at the World Cup in South Africa. I wouldn’t consider myself a selfish player, but for the first time I really felt like I was playing for so, so much more than the team, or myself.

I felt like a soldier, almost. I had a responsibility to the flag, to the kit, to the people back home. Because I know how proud we are. I know where that pride has come from. Serbs have been through more than people from most other countries can even imagine, so when we get a chance to show ourselves to the world … we’re going to do our best to be who we are: fighters.

The results didn’t go our way, but I’ll never forget that 1–0 win over Germany. That was reassurance that we are a footballing nation, that we belong.

That tournament, despite our going out in the group stage, gave me confidence going to Manchester.

I consider my time as a Citizen as one of the most beautiful periods of my life. Two Premier League titles, one FA Cup, two League Cups — I won’t forget those. And, of course, there was the best moment.

Everyone remembers where they were when they heard …

“Agüeroooooooooooooooooooooooooo!”

We’ll always have that.

Honestly, I still consider City my club. A few months ago, when City were close to the title, Edin Džeko and I were watching the Manchester United-West Brom game on our team bus on the way to our match. United lost, which is funny because West Brom were last in the table. ? And Manchester was blue, again. It was a nice moment for us. I will remember those fans forever, and the club holds a special place in my heart.

Now I’m back in Rome. And it feels a bit like 2010 again. I’m getting ready to go represent Serbia at another World Cup, with my wife, Vesna, and our two children in Italy watching. My parents are still in Serbia and they won’t be coming to Russia because, well, I don’t let them. My mom has been to four games in my life and I’ve lost every single one, so she’s banned. And my dad gets too nervous and has to smoke like five cigarettes during the game — he needs to be at home.

But I’ll be there, and Serbia will be there. I remember the pain of losing in the group stage eight years ago, I don’t want to feel that again. I have the armband now and I feel a responsibility to be the leader we need — the one I dreamed I could be.

I think we have a chance because we’re flying under the radar. You probably have no idea what to expect from us, right?

We like it that way. You probably don’t know how creative Sergej Milinković-Savić is, or how talented Dušan Tadić is, and that’s fine. We’ll do our best to show you. Because a chance like this for us to represent Serbia was a long time coming. A lot of the players on our team remember the war, remember the bombs, remember the sirens — we know what our country suffered to get here. And out of that conflict came great relief, great opportunity, and a great generation of footballers.

We were all a part of that, we all remember. And now we’re going to take our chance.