The Things I’ll Never Forget

I’ll never forget the older kids making fun of me for showing up to church wearing those old red, white and blue Harlem Globetrotters wristbands. I’d turn up to the Sunday service wearing those things with a polo shirt like I was Sweet Lou Dunbar. All the older guys would be looking at me from the pews just shaking their heads like, “Barry, what in the world, man?”

See, my mother was one of those incredible ladies who used to go to church twice on Sundays. Once was never enough. She needed to talk to Jesus after dinner, too. My friend lived at the top of one of the few hills in Wichita, so me and my brother used to run up there after dinner and play tackle football in our church clothes. We would pray that my mother’s old car wouldn’t be able to make it up that hill to come get us. We knew that if we made it past five o’ clock without hearing her muffler, then we were safe. That was just about the best feeling in the world.

Sometimes she would get clever and send one of my younger siblings up the hill to come collect us, and we used to just run.

Clear as day, I can still see my friend Kerry Gooch drawing up plays in the dirt. If you love football, then you never forget that feeling. You remember what it feels like to be the young kid with all the older guys, just wanting that ball in your hands, running to daylight. Doesn’t matter where you are. A backyard. A parking lot. That feeling is ... pure.

In my mind, I was Terry Metcalf. Never Earl Campbell or Larry Czonka. Terry was smaller, like me. There was something about the spins, the jukes, being light on his feet. The creativity. The imagination. He was an artist.

I was always outside, because when you have 10 brothers and sisters, what else are you gonna do? When I think about my house, I just see … bodies, man. Every time my mother had another baby, the hospital used to send this vanilla sheet cake to the house as a little homecoming gift. I remember all my brothers and sisters being so excited — for the new baby, but also for the cake. Because that icing was the good icing. That cake used to last about three minutes in our house. I mean devoured.

I remember I begged my dad to get me some Juicemobiles. The young fellas will not understand what I’m talking about, but O.J. was bigger than life back then. When he came out with the Juicemobiles, that was like the Jordans of our day. I played my first peewee football game in gym shoes, and I did good enough to convince my dad to buy — well, let’s call it an investment in some Juicemobiles.

My dad worked on a roof for most of his life. Well, he did everything, actually. He was the neighborhood handyman. If it could break, he could fix it. I mean, real blue-collar. He lived for two things: his friends, and the Oklahoma Sooners. He was older than old-school. I used to work with him in the summers, and one day we stopped for lunch at his buddy’s restaurant, and his buddy started complaining about “all these athlete role models.” And my father slammed his fist on the table and he said, “Role models? I’m my kids’ damn role model!!!”

He was the reason I never spiked the football. I remember Tony Dorsett scored a touchdown on Monday Night Football and he did some kind of celebration. He probably just put his arms in the air or something. So in my next peewee football game, I went out and tried to imitate whatever Tony had done. After the game, I got into my dad’s car and he said, “Oh, you think that’s cute? If I ever see you mimicking those guys on TV.…” And that was it. After that, I started just handing the ball to the ref.

My dad was such a crazy Sooners fan. When I chose Oklahoma State on Signing Day, the head coach came to our house to say hello to the whole family, and I can still see my father standing in the doorway, turning back to Coach and saying, “Well, I think he’s making a huge mistake,” and just heading out the door! I don’t think I saw him for a week. Mind you, I wasn’t even recruited by the Sooners. Me going to a rival just offended his sensibilities that much. I remember looking over at my mom, and she was just sitting on the sofa smiling, because I’m sure she was just thinking, “Hey, I got 11 kids, so if you’re getting a free education, you go wherever you want, Barry.”

I don’t know why I’m remembering this now, but when I was maybe 13 years old, I was just walking around the streets with a couple of buddies. We weren’t even up to anything bad. We would just stroll the neighborhood. This is in Wichita, mind you. And my mom found out about it from somebody and she said, “Barry. You’re not just going to be walking around with these guys, you understand? I don’t want to hear stories about you walking ever again.” There’s a good lesson there, but I can’t quite explain it.

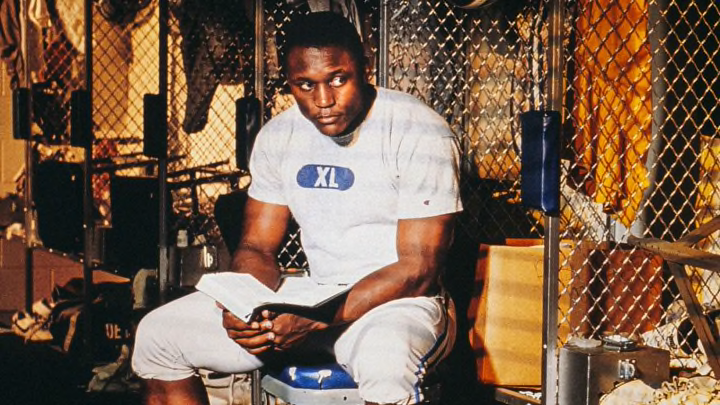

I used to almost fall asleep on the bench during games. For me, it was almost like meditation. If I had a secret, it’s that I always tried to be as relaxed and as clear-minded as possible. I remember my running backs coach at OSU used to keep a cup of water on his desk during our film sessions. Whenever I’d nod off, he’d sprinkle me. People used to laugh, but for me, I needed the quiet in my mind. It was almost like a Zen state, I guess. Even when I was on the bench in the middle of an NFL game, I felt very still.

Bedlam, 1988. I was in the running for the Heisman when the Sooners came to Stillwater. I remember my dad and all his buddies came down from Wichita, and he told me, “Son, I hope you have a great game. But I was a Sooners fan long before you got to Oklahoma State, and I’ll be one long after you leave.” After they won the game, I heard that he got to go into the Sooners locker room and Barry Switzer gave him a hug.

Honesty. That was my father. In life, you meet a lot of diplomats. You meet a lot of people who tell you what you want to hear. But I always thought my father had the best life, even though he worked his hands to the bone, because he was always 100% himself — and people loved him for it. I loved him for it. After I won the Heisman trophy, we kept it in a glass case at his buddy’s restaurant in Wichita. Right next to a Sooners helmet. That was us.

You want to talk about “I’ll never forget”? Man, I remember we were playing the Cowboys on Monday Night Football. This is 1994. Emmitt, Troy, Michael. National television. I’m running back to the huddle and I look over and see my dad standing right there on the sideline. He’s smiling from ear to ear. But he’s not on the Lions’ sideline. No, no, no. He’s on the Cowboys’ sideline with his old buddy Barry Switzer. He was probably giving Barry tips! Thankfully, I got them back that night. I think I had 190-some yards, and we won in overtime. That was a feeling.

If there’s one run that I’ll take to my grave, I think it’s the run against the Patriots in ’94. The triple cutback on the defensive back. Just making him spin around like that, it was something that I used to daydream about when I was a kid. You know, back in grade school, they asked everybody to write down that they wanted to be when they grew up. I wrote carpenter because of my dad. But I used to secretly daydream that I was an NFL running back. I would have these outrageous fantasies of me running wild, doing crazy cuts and jukes, making people miss. And that run against New England is probably the closest I ever got to living out my imagination.

I think the meaning of life probably has something to do with being at peace. I probably picked that up from my mother. When I sent that fax to the local newspaper announcing that I was retiring from the game, I was completely at peace. I knew that I was never going to find anything in my life that would match football. But that was O.K. I was 30 years old and I knew it was my time. I had lived beyond my wildest dreams. How could I ask for more?

The most inspiring memory from my life has nothing to do with football. You’re playing a kids’ game out there. That’s nothing incredible. What’s incredible is my mother, after having 11 children, working a job at night and finishing her nursing degree during the day. How do you do all that and still go to church twice on Sundays?

I can still see her in our kitchen, making us breakfast in the morning after she just got home from work. Kids running everywhere. Legs, arms, bodies. A bundle of chaos. I can see her trying to corral somebody with one hand, making toast with the other hand. Whatever my legacy may be, whatever comes to mind when people think of the name Barry Sanders, I wish that they would think of her, too. She made all the sacrifices so that I could live out my outrageous daydreams — so that I could run free.

Man, I can still hear my friend Kerry Gooch whispering, “Alright, this is where you’re gonna go, Barry.” Drawing up the plays in the dirt with his finger. Just praying that her car wouldn’t make it up that hill. Just praying that we could keep playing football all night. Forever. Until the end of time.