What I Know

Let me tell you what I know about Lexington, Kentucky.

For much of my life, it’s been home. It’s where I really grew up, where I really learned who I was, where I really started to play basketball.

And if you’re going to ball, it’s gotta be in Lexington. It’s home to the Wildcats. It’s home to Big Blue Nation. Because here’s the other thing I know, there are no better fans than BBN. They’re loud, they’re crazy, they’re standing all 40 minutes. When you come into Rupp it’s you versus 23,000 fans. They’re relentless. They’re family.

Obviously, I’ve been around BBN for a while, but I only learned just how deep it runs when I was a freshman in high school and went to watch the national championship in 2012.

That weekend was crazy. It was nothing but positivity. Everyone was happy. We had thought about it all season. With each game and each win, we had thought about it: national championship. And here it all was, coming down to the last two minutes in the final game: Kansas had cut our 16-point lead to five. Even the toughest Wildcats fans had their head in their hands — they couldn’t watch. Because all season long, with each game and each win, they had thought about it, too: national championship.

Their screaming reverberates inside the Superdome: “Go Big Blue! Go Big Blue! Go Big Blue!”

Whistle blows. Time out. On cue, the band plays, “On! On! U of K.”

We hold on to the lead as the last few seconds run out. BBN is rumbling, roaring, losing its mind.

National championship.

That’s when I really felt the power of BBN. And as much as I could try to explain, it really was an indescribable moment.

The first person I saw was Darius Miller. I was just yelling, patting him on the back.

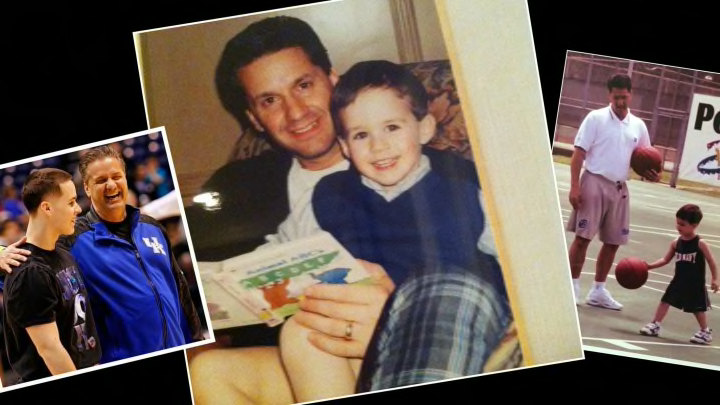

The second person I saw was my dad.

Through it all, he’s always been Dad to me. To many other guys and to BBN, of course, he was Coach Cal. We hugged and laughed and cried.

This may seem crazy, but after all that, I knew I had to leave Lexington. Leave my high school. Leave Big Blue Nation.

So two years later, I did.

A lot of people assume that because of my last name they know who I am. They want to tell me where they think it’s gotten me or why I’m here as a walk-on for Kentucky.

But, now, let me tell you what you may not know about me.

***

I’m the baby of our family. I’ve been going to basketball games since before I was born. When my mom was pregnant with me, she would load my two older sisters into the car and head to Continental Airlines Arena, where Dad was coaching the New Jersey Nets. That’s how it started, and since then, basketball games have always just been a part of my life. No defining moment, no big realization of who my dad was, or what he did — just the fact that I’ve always had a basketball in my hand.

After we moved to Memphis in 2000, I got into a more structured basketball routine. I started playing in church leagues and on AAU teams. I would shoot around on my own whenever and wherever I could, including in my bedroom, where I had one of those hoops that was fixed to the wall. In front of my Muhammad Ali and Michael Jordan posters, I’d horse around in my room, trying to shoot and dunk. I put a hole in the wall once trying to slam dunk. It was actually my mom who ended up fixing the basketball hoop — my dad’s a little hopeless when it comes to DIY home repair.

As I grew older in Memphis and then in Lexington, I became aware of my dad’s impact on the game. I also realized how badly I wanted to play. And what better way to learn than by watching players like Dajuan Wagner, Derrick Rose, DeMarcus Cousins and John Wall?

While other kids and their families had Christmas holidays or summer vacations, my family had March Madness. March in the Calipari household is a sacred time. We usually didn’t go to the conference tournaments. But the NCAA tournament? Now that we always made time for. Those first few years, I just thought it was fun. I’d get out of school (and have a ton of makeup work to do while I was gone). They were our family trips. We’d either go with the team or fly out to the locations on our own. I didn’t think too much about why we were there, or why I could take shots on the court during shootaround.

Of course, there were downsides. People will just talk to you, slamming Coach Cal, unaware “Coach” was actually “Dad” to my sisters and me. The first couple times that it happened I didn’t know how to handle it. I would start looking at them like, You know that’s my dad, right? or, You know you’re talking about my family, right?

But it is what it is. As I’ve matured, I understand that people are going to either hate him or love him, so I can’t really take it personally. People see him and think they know what he’s like. But to us, he’s our dad, who tells corny jokes and is obsessed with war documentaries.

Growing up around the team and the tournaments developed my love for basketball. It made me want to pursue it because I saw first-hand the opportunities it could give me in life, whether playing in college or, yes, even coaching at some point. But like so many kids who say they want to play basketball — even being around my dad and his teams — I didn’t really take into consideration how much time and dedication it would require. I soon realized I needed to step up my game. So when I went to Rupp, I was never really on my feet going crazy. I would observe, I would watch and I would try and learn from what was happening in the game. And then I’d try to apply it to my own games.

You probably think you have an idea of what it was like for me to have “Coach Cal” in the stands. But to be honest with you, he was actually kind of quiet. Seriously. He never really yelled or tried to coach me during my games — he already knew how that was with parents and his own players. It was after my games that we had our moments. If he saw something that needed to be fixed, he’d go through whatever change I needed in my game. But he’s a mellow guy.

Unless I was having my own outburst on the court.

During an AAU game in the summer before ninth grade, my attitude was getting really bad. My body language wasn’t great whenever I was reacting to what I thought were bad calls. And as the halftime buzzer sounded, I saw, out of the corner of my eye, Dad weaving through the parents in the bleachers, making his way toward me. Just that classic dad en-route-to-lay-down-the-law walk. The man was on a mission. And I knew it wasn’t good. He walked over, grabbed me and told me that if my attitude didn’t change, he was going to take me off the court in the middle of the game and take me home. That was probably the most I ever saw the Coach Cal side of him.

Even if my team was down by 20, I never copped an attitude like that again.

And the more I wanted to elevate my game, the more I knew I needed to leave Lexington. You’ve all seen this movie before: The son feels the need to forge his own path. A lot of people just think my basketball career has been handed to me because of my dad. They don’t see the late nights, the workouts, the extra hours I spend at the gym. They see his games at Rupp, but they don’t see that just a few miles away, I’m in front of the hoop at our home, trying to perfect my shot. They see the name on the back of my jersey, but they don’t see just how hard I’ve worked to put it there.

But you can’t be mad at people for what they don’t know.

Two years ago, I really started to think about leaving for prep school. Of course I knew I couldn’t just stroll into Dad’s office without a plan, so I consulted our second family: his coaching staff.

I talked with Kenny Payne, I talked to Rod Strickland and Coach Antigua, who are both now at South Florida. Strickland had gone to Oak Hill, so he knew what prep school life was like. They all thought it would be an opportunity for me to get better as both a person and a player. From a skill standpoint, I’d be playing against tougher competition, and it would help me to be more independent and to learn things on my own.

When I felt like I had done enough recon, I walked into his office and said, “What do you think about me going to prep school?”

“I think it could be good for you.”

He knew what I was trying to do and how I was trying to better myself. I know it was hard for him to let me go, but the fact that he knew I wanted to pursue a basketball career helped him understand that it was going to be fine. From there, he was still just Dad, with a little Coach Cal sprinkled in. We talked about why it would be good, why I would need to do it, what fit I would need, who I would need to play with and how the coaching should be. And once we figured that out, we visited a few schools to get a feel for what they were like. At The MacDuffie School in Granby, Mass., for the last two years, I’ve grown my game. I’ve studied players like Kyle Korver and — sorry, Dad — J.J. Redick. They’re very, very skilled shooters, and even though they’re not the most athletic guys, their footwork, their change of speed, is incredible. They have this ability to read screens and an IQ for the game.

It’s been hard not being around Lexington these past couple of seasons, not going to all the games like I used to. Before our games — his in Kentucky, mine in Massachusetts — we’d call each other and wish each other good luck and say I love you. It’s something my family has always done before every game, wherever we’ve lived. Plus, Dad and I have had plenty of time to catch up on the Elite Youth Basketball League circuit. He used to bring me out to Las Vegas for the EYBL summer tournaments when he was recruiting — call it another Calipari family tradition — but now, I’m competing in them. A lot of guys I’ve played against, he’s recruiting.

And last summer, I had the chance to play some pickup ball with his Kentucky team. It was the first year I was really able to hold my own. It showed me how much I needed to up my game, and the level of guys I’d be going up against if I wanted to play in college. Of course, wherever I went to play, there’d be talk. I knew I’d be held to a higher standard. So just before the SEC tournament in March, I had a break from school and another talk with my dad.

I told him that I was thinking about coming to play at Kentucky.

He asked if I knew what I would be getting myself into, how hard it would be — probably the hardest thing that I’d ever done. “The way you work now, you’ll have to take it to a completely different level, whether it’s workouts, watching film, classwork.” A week later, we made it official: I would be a walk-on at Kentucky. More than anything, the team has a staff I trust, a staff a grew up with. It’s Big Blue Nation. Like I said, they’re family.

***

So let me tell you what I know about Lexington, Kentucky.

It’s going to be home — again. I’ll get to see my mom more often. I’ll be back with Big Blue Nation. I’ll be at Rupp wearing my Kentucky blue with CALIPARI on the back, the name I worked hard to put there.

And after growing up around college basketball, what do I want the most when I’m finally there? It’s not the gear, or the flights, or anything like that. I want that Kris Jenkins moment. I want a buzzer beater. I want to think about it all season, with each game, with each win: national championship.

And the first person I want to see after we win is my dad.