The Streak

Looking back, the night I broke the consecutive games record unfolded in front of my eyes like a movie. For years, I didn’t want to see any of the replays of the game. I didn’t want to see any different angles. I just wanted to remember it through my own personal camera lens.

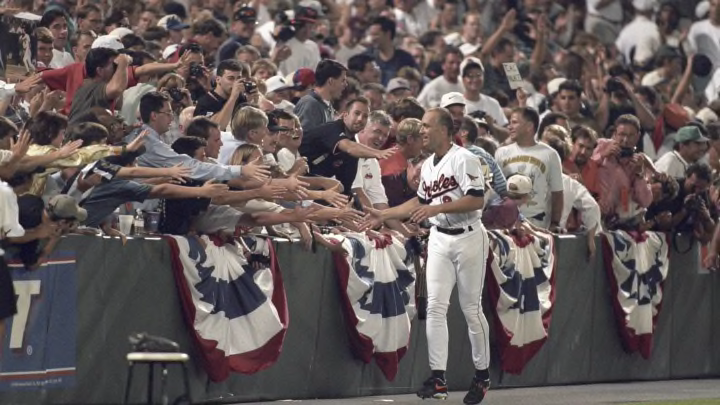

The game became official when we were batting in the bottom of the fifth inning. At that point, everybody stood up and cheered. I acknowledged it as much as I could, but I started to get a little embarrassed the longer it went on. We were in the middle of the game, so I thought the interruption wasn’t fair to the pitchers and the other guys who were playing. After one of the curtain calls, when I tried to go back into the dugout, Rafael Palmeiro said, “Ok, you’re going to have to take a lap around this ballpark or we’ll never be able to start this game again.”

I laughed it off, but when I walked back out of the dugout to wave again, he and Bobby Bonilla pushed me down the line. I figured, “Ok, let’s try this to see if we can get the game started.” Once I started down the line, though, the celebration became a lot more personal. I recognized all these people by face, recognized them by name. These figures who had been there for me since the beginning were here tonight to watch me play. By the time I got around the left field bleachers, it didn’t really matter to me whether the game would start again.

I remember my dad was in the skybox, and I looked at him a couple times and gave him a sign. I felt like I was expressing all these emotional things that were never really said growing up. There were a million emotions being shared between us through just a look.

I always say that catching the last out of the World Series was the best professional moment of my career and the night of 2,131 was the best human moment.

It meant a lot to me that he was there because it all really started with my dad — baseball, the Orioles, everything.

My dad was involved with the organization his entire career. He didn’t get to fulfill his dream as a player in the big leagues — he got hurt in the minors — but he used his deep knowledge of the game to become a coach. And he was a great one. I remember a specific speech my dad used to give everybody during Spring Training. He would say, “Welcome to the greatest organization in baseball. If you make it through our Spring, you will play in the big leagues. Might not be with us, but you will play in the big leagues.”

That’s what I grew up with. The Orioles were a well-respected, well-run organization. My dad felt a special pride in the team, so my entire family grew up with a special pride in it as well. When I entered the draft right out of high school, I got a lot of attention from other teams. There were a lot of scouts telling me that I was going to be the first overall pick, and the Orioles were drafting in the 20s. I had mentally prepared myself to go to another organization, but in the moment of truth, I really wanted to be drafted by the Orioles. When it actually ended up happening, I couldn’t have been happier.

I got called up by the team for the first time in 1981, after the strike ended. We were playing against the Royals and Earl Weaver yelled for me to pinch-run for Singey (Ken Singleton) at second base. I ran out onto the field, and my adrenaline was just pumping like crazy. Wearing that Orioles uniform and walking onto the field at Memorial Stadium was a dream come true. I took a lead off and Royals second baseman Frank White tried to pick me off the very first play. I got back safely at second base. Frank caught the ball and tagged and said, “Just checking kid.”

My career started with a bang. We were pretty good in my very first year. We made it to the brink of the playoffs and lost to the Milwaukee Brewers on the last day of the regular season. The next year, we learned from that and won the World Series. In ’84, we were still really good, but the Tigers were better — they started out that year 35-5. In ’85 and ‘86, we were very competitive, but then we started to lose some talent. As the season progressed, we went into a major rebuilding mode. At the end of the ’86 season, Earl stepped away from baseball and my dad got the opportunity to take over as manager of the Orioles.

We struggled through ’87, my dad’s first year, and then went 0-6 to start ’88. I didn’t think the slow start was the end of the world because we had been in a lot of those games and could easily have been 3-3 if we had gotten a couple of hits at the right time. But the talent just wasn’t there.

I’ll never forget driving to the stadium and hearing on the radio that my dad had been fired. When I got there, Frank Robinson called me and Billy, my brother, who also was on the team at the time, and told us he had taken over as manager. We were both pretty angry because we thought dad had been betrayed. After all our family had given to the franchise, we felt like he had never really been given the opportunity to succeed.

I really believe my dad’s firing threw the team into turmoil. We lost 15 more in a row and were getting national attention for all the wrong reasons. In hindsight, it was probably a good thing for the organization, because they had to face the reality of the state of the team. Still, that was the toughest stretch of my career. I was constantly part of trade rumors, and there seemed to be a new one every day. I was sure that would be my last year with the Orioles, and for the first time, I actually wanted to play somewhere else.

But as the season progressed, I started to play better, and the negative emotions died down. I began to consider things differently. Looking past the business decisions that were made, I realized that the Orioles were my home, and the only team I ever wanted to play for. I never looked back from there.

In 1989, I passed Steve Garvey and moved into third place with 1,208 consecutive games played. That was really the first time my streak started to get national attention. I tried not to think about it as much as possible. One of the ways I went about that was by intentionally trying not to learn much about Lou Gehrig. Don’t get me wrong, I love reading about the heroes of baseball’s past, but I never wanted to learn about Gehrig’s streak. It was almost a way of protecting myself — I assumed he was just playing and loved to play, so I never wanted to learn his motivations beyond that. I didn’t think anything good could come from me trying to be someone else. My only job as a baseball player was to come to the ballpark ready to play, and if the manager thought I was one of the nine guys who could help the team win that day, he would put me in the lineup. I never told any of my managers, “I’m going after Gehrig’s record, so put me in the lineup.” I just wanted to play.

The only time the streak ever really weighed me down was when I was slumping or the team was slumping. If I was slumping, a whole bunch of critics would line up to call me selfish. It’s always hard to be in that position and think that maybe you’re hurting the team by staying in. Still, I had the philosophy that the selfish player is the one who, when things are going bad, takes himself out of the lineup. Selfish is when your team is facing the game’s best pitcher, and you’re 0-20, and you say, “Okay, somebody else go out and deal with this.”

I remember this one time in Boston, we played like 15 innings on a Saturday night and we had to come back for a Sunday day game. I remember feeling physically beaten down, and we were going to be facing Roger Clemens hours later. It was especially hard to hit against Roger during the day because he was tall enough that from the plate it looked like he was throwing it out of the crowd in center field. If it was light out, you didn’t really stand a chance of seeing the ball. I was already in a slump, and I remember thinking, “Man, it would be really easy just to say, ‘I’ve been playing all these games, somebody else go out and try to meet that challenge.’ ” That’s a cop-out, though, and it’s not how I was raised to approach the game or my life as a whole.

Around game 1,800, all the critics suddenly turned positive and said I had to break the record for the sake of baseball. That’s a lot of pressure, because I internalize a lot of stuff. I would go back and think about things, and there were a lot of times that I thought, Well, maybe it would be better if I take myself out of the lineup. Maybe it’s better if I look out for myself and handpick off days. I would always come to the same conclusion, though. Each day I came to the ballpark to meet a challenge, and whatever the challenge was, I was willing. Because I was willing and because I was durable, the managers kept scribbling me into the lineup.

When I came within a full season of breaking the record, the pressure started to really build and continued to spike up until the last week or two before I broke it. Everybody was making preparations, and there was so much anticipation. It felt like there was a finish line.

Reflecting on it all these years later, I realize that the streak was never about the streak. It was about giving all I could for the team I loved. When the banners on the B&O Warehouse changed from 2,130 to 2,131, I could picture my whole career with the Orioles — my whole life with the Orioles, really.

When I looked up and saw my dad in the skybox, I saw him delivering those Spring Training speeches when I was little. It felt like I was home.