Ali

When I was eight years old, an older white man with a big belly and tattoos on his arms approached me while I was hitting the heavy bag at the Boys Club. His name was Carter Morgan.

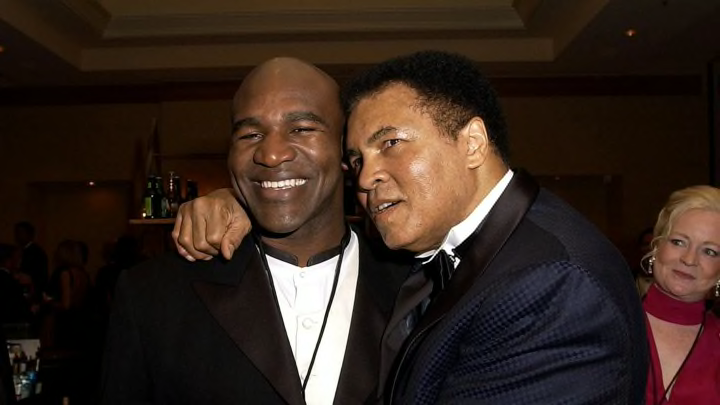

“You’re pretty good,” he said. “You could be the next Muhammad Ali.”

It was 1970, and Ali was still undefeated and preparing to return to boxing from a three-year exile to fight Jerry Quarry in Atlanta. Ali was the most charismatic figure in sports and he was on his way to being the greatest fighter and most revered athlete in the world.

For me, the rest is history. I became an Olympic medalist and the only undisputed and undefeated cruiserweight champion in history. I became the only four-time World Heavyweight Champion. I defeated legendary fighters like George Foreman, Mike Tyson and Larry Holmes. I established myself as one of the greatest ever.

But no matter what I accomplished — or what anyone accomplishes after me — there will never be another Muhammad Ali.

When I look back on my life and boxing career, one of the greatest nights of my life actually wasn’t even about me. It was about Ali.

*

I lost my first professional fight to Riddick Bowe in 1992. Along with it, I lost the World Heavyweight Title I won in 1990 against Buster Douglas and successfully defended against George Foreman, Bert Cooper and Larry Holmes. I was 28-0 before that unanimous decision loss to Riddick Bowe.

I got redemption a year later when I beat Bowe by majority decision to win back my World Heavyweight Title, but the rubber match in 1995 was one of the toughest tests in my life. I was suffering from Hepatitis A, and Bowe pushed me to the limit — as far as I’d ever been pushed physically in my life.

I lost by TKO for the first time in my career.

After the fight, I was hurting, both physically and mentally. But with the 100th anniversary of the Olympic Games set to take place in my hometown of Atlanta the following year, I wasn’t about to give up. In the post-fight press conference, a reporter asked me what my next move was gonna be, and I told him. I was gonna be the World Heavyweight Champion again and I was gonna carry the torch at the Atlanta Olympics.

All the reporters laughed, not just at my goal to be world champ again, but more about my goal of carrying the Olympic torch. People thought it was ridiculous.

Of those two goals, there was one I could control: becoming world champ again. But I couldn’t control carrying the Olympic torch. That would be decided by the U.S. Olympic Committee. As the games got closer, I hadn’t been offered to carry the torch, and I was not feeling good about my odds of being invited.

At midnight the night before the Opening Ceremonies, I was at my home in Atlanta when my phone rang. I thought, Who’s calling my house at midnight? It was Dr. Harvey Schiller, executive director of the U.S. Olympic Committee.

“Evander,” he said. “I have good news and bad news. The good news is, we’d like you to carry the Olympic torch into the stadium during the Opening Ceremonies.” At first I thought someone was playing a joke on me. I was so surprised I almost didn’t hear the bad news.

“The bad news is, you won’t be lighting the cauldron.”

I was ecstatic. I didn’t care that I wouldn’t be lighting the cauldron. Just to have the opportunity to carry the torch into the stadium was an honor, especially since I thought I had no chance because the ceremony was the following day and I hadn’t been invited.

I asked who would be lighting the cauldron, and he said, “Can’t tell you that. It’s a surprise.” He also told me that I couldn’t tell anyone — not even my family — that I would be carrying the torch. It was all part of the committee’s plan to host one of the most memorable Opening Ceremonies in history. They were keeping it a secret.

The next night, at the Opening Ceremonies, I was in the stands with my family, and I remember handing my son the video camera — remember, they don’t know I’m going to be carrying the torch into the stadium — and telling him to make sure he keeps it focused on the entrance where the person carrying the torch is going to come in.

When I left the stands to go down to carry the torch, I couldn’t tell my family where I was really going, so I told them I had to go down and talk to some people real quick. On my way down, I ran into some delegates from the state of Georgia, and they were still furious that I wasn’t carrying the torch. Some of them were very emotional, calling it disrespectful that I — an Olympic medalist and a person of color — would not carry the torch in my own hometown.

I tried to console them, and I wish I could have just told them I was going to carry the torch, but I couldn’t for two reasons: I wasn’t supposed to tell anyone, and I had to go carry the torch and I was running late!

When I finally got past them, I made my way down to the tunnel where I was gonna bring the torch into the stadium. There was a 15-foot ladder at the end of the tunnel, and after they lit my torch, I had to wait at the end of the tunnel at the base of the ladder and wait for the green light to climb up onto the stage above.

The tunnel was only about seven feet tall, and I noticed it had fire sprinklers on the ceiling, and here I was, standing 6-foot-2, holding the Olympic torch.

I told myself: Don’t hold it too high. If those sprinklers go off, you’ll climb onto the stage in front of a packed stadium and onto TV sets all over the world soaking wet. It’ll be a huge embarrassment and you’ll forever be the guy who extinguished the Olympic flame.

I could feel the flame against my face as I waited at the end of the tunnel holding the torch directly out in front of me, terrified of the sprinklers.

Finally, I got the green light and climbed the ladder — with one hand because I was holding the torch in the other — and emerged onto the the stage.

That torch started in Olympia, Greece, like it always does, and was carried by a chain of athletes over 16,000 miles to get to Atlanta, and until that moment, everybody thought I was being left out. But when I stepped out onto that platform and they showed me on the big screen holding the torch, the crowd went crazy.

I joined Greek hurdler Voula Patoulidou and we jogged around the stadium track, and together, we used our torch to light the torch of Olympic swimmer Janet Evans for the final leg of the relay.

Janet Evans proceeded toward the main stage, where she would hand it off to the mystery athlete who would light the Olympic cauldron.

When she got to the top of the ramp and stepped onto the stage, the surprise Dr. Schiller couldn’t tell me on that midnight phone call the night before was revealed, as Muhammad Ali emerged.

As Janet Evans lit Ali’s torch, a video played on the big screen displaying all Ali had done as an athlete and a humanitarian. It showed what he stood for and that he used his fame to bring attention to the greater causes that could help mankind. And as everyone in that stadium re-lived Ali’s life and career on that screen, I was reminded of Carter Morgan.

You’re pretty good. You could be the next Muhammad Ali.

Ever since those words came out of his mouth, I modeled myself after Muhammad Ali, both inside the ring and out. I didn’t just want to be the boxer Ali was, I wanted to be the man he was. For over 25 years I had studied Ali’s every move, from his jab and footwork to his philanthropy and resolve to stand up for what he believed in.

I wanted to be the one to light the Olympic cauldron, but when I saw Ali emerge on stage — arms shaking and fighting the Parkinson’s that was taking over his body — all I could think was, They chose the right man. I wouldn’t have had it any other way.

I got to represent my country, my sport, my family and my community in my hometown on the biggest sports stage in the world. It was one of the greatest nights of my life, and it was a night that wasn’t even about me. It was about Muhammad Ali.

As it should have been.