Story of My Life

Born: 1972

When I think about my childhood, one thing comes to mind: Love. We didn’t have much money, but we had love in our house. The neighborhood where I grew up in Detroit was pretty rough. Our house was tiny. Man, everybody’s house was tiny. In the kitchen, there was no space to move. I look back on it now and I realize how tight the conditions were. But when you’re a kid, you don’t think anything of it. I’d say it was crude but effective.

1978

If you met me when I was six, I was a chubby, mischievous kid. My saving grace was that my mom was a bowling teacher and she taught me and my two older brothers to play when we were really young. Bowling kept us busy, and most importantly, inside. On the weekends, we traveled all over the state to bowling tournaments, and it kept us out of the streets. Our parents did a great job of shielding us from the reality of our neighborhood.

1981

That mentality extended to my education. My dad worked two jobs and my mom worked full-time so that they could afford to send me to this private Lutheran school starting in the fourth grade. They were doing their best to keep me out of trouble. Only problem was, I had this itch…

1982

When I was 10 years old, I got a whuppin’ that changed my life. It wasn’t from the streets, it was from my mother. See, I wanted to go play down at the arcade, but I was broke as a joke. I saw my mom’s purse sitting out on the kitchen table and I couldn’t help myself. In my mind, I “borrowed” 20 bucks.

Alright, I stole it.

Back then 20 bucks got you a whole ton of games. So I went down to the arcade and played all day. When I got home, my mom knew I stole the $20, and I got a beatin’ so bad. I needed it. Because it really helped me to understand that there are certain things you just don’t do. Stealing is one of them. In Detroit, at least in my household, you might be poor, but you better be honest. You work for what you get. It was a painful $20 lesson. Space Invaders wasn’t worth the whuppin’.

1984

As I got into my teens, I was big and I was fast, but I actually didn’t play organized football until I got to high school. In middle school, we played football in the street right in front of the house. The streets weren’t paved great, so you might be playing against 11 defenders — but they were like five guys and six potholes. The rule was, it was touch on the cement, and tackle if you went into the grass. Well, sometimes it was tackle on the cement, too.

This might sound strange now, but the summer before I started high school, I had to make a decision: bowling or football? By that time, I was an all-city bowler. The problem was, Ohio State was the only school that offered bowling scholarships. And it was only a partial scholarship. Bowling wasn’t going to pay for my college degree, so I thought, Alright, let’s try this football thing.

Within a few years, I was the No. 1 fullback in the country and the No. 2 linebacker.

1988

One of the first recruiting letters I got was from Notre Dame, and I’m thinking, Notre Dame? Notre Dame in Europe?

I didn’t watch college football. At 17, my plan was to be an electrical engineer. My father ran the city of Detroit’s buildings and safety department. He didn’t have a college degree, but he rose to that position through hard work and discipline. He barely saw any of my high school games because he was always teaching night school on Fridays. My whole goal was to follow in his footsteps. So my decision came down to Notre Dame vs. Michigan because both schools had great engineering programs.

The turning point was when the little guy showed up.

1989

I’ll never forget when Lou Holtz pulled up to my house to visit with me. It was already dark. My parents and I were sitting on the porch. He was deep in the ’hood, now. This is before GPS and iPhones. His assistants were sitting in the car, and they were looking up at the porch a little sketchy like, Is this the right place? We good here?

But Lou got right out of the car, walked straight up to the porch, smiling from ear to ear. And in that high-pitched voice, he says, “Hiya doin’, Mr. Bettis! Hiya doin’, Mrs. Bettis!”

He quickly realized who was the boss in the house. He totally sold my mother. He was talking to her, he wasn’t talking to me.

Imagine that high-pitched voice, going a mile-a-minute:

“Mrs. Bettis, you’re gonna love this place! It’s so beautiful, oh my goodness, oh my goodness, da-da-da.”

By the time Lou left, my mom was like, “You’re going to Notre Dame.”

She was not discussing it any further. That was it.

1990

When my dad dropped me off at Notre Dame, I got out of the car with my bags and he gave me a hug and said something I’ll never forget: “I don’t have any money to give you. But I got a good name. Don’t screw it up.”

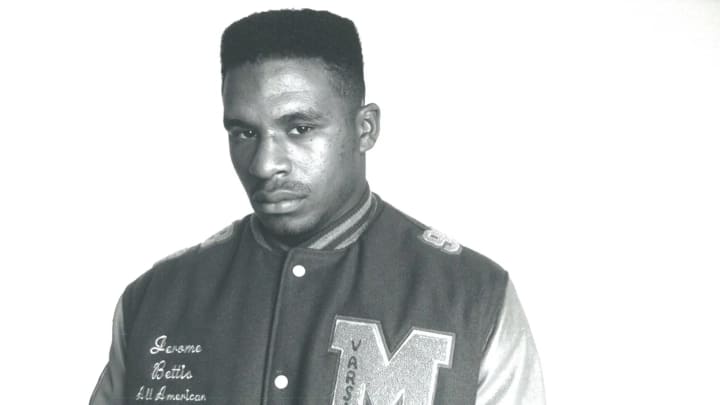

1992

If I could change one thing about college, I’d go back to our game against Stanford my junior year. I fumbled twice. That loss really hurt our chances to play in the national championship. Other than that, I had no regrets in my three years at Notre Dame. I busted my butt academically. My mom and dad drove to every game. The only game they ever missed was when we played Air Force out in Colorado. That’s the thing that made my whole journey so special. Football wasn’t just me. It was us. I took the field with my whole family behind me.

1993

At the end of my junior season, it was clear that I was ready to make the leap to the NFL. Coach Holtz had scheduled a meeting with me and my family. I’m not gonna lie — I was nervous. I’m thinking I’m going to have to convince him. We sat down, and coach said, “You’ve done everything that you can do here. It’s time for you to go.”

I’m like, Wow. O.K. Here we go.

I’ll always love Lou for the way he handled that. He put my family at ease.

Within a few months, I was putting on an L.A. Rams hat at the draft, and then I was moving across the country for training camp. That’s when the ride sped up real fast. And to be honest, it was going pretty smooth.

Until Houston. That’s when it got very real. That’s when I had my “welcome to the NFL” moment.

We were playing the Oilers at the Astrodome. We had the ball at the goal line. I went into the game. I’m like, Perfect. Let’s pound it in. Let’s go. When the coaches drew up the play, they said, “Alright, the linebacker in this gap here is going to be unblocked. But that’s O.K., because the play’s going over here.”

And that was some bullshit.

Ball is snapped. I make my cut, hit the hole, and boom. Right as I cross the goal line, guess who lights me up from the blind side? The unblocked guy. I scored the touchdown, but when I got up to celebrate, I had blood coming from my neck.

That’s when I learned that in the NFL “unblocked” means, “that’s your guy.”

Lesson learned. I started running over those guys.

1996

By the spring of ’96, it was becoming clear that I didn’t have a future with the Rams. What people might not realize is that my agent and I carefully orchestrated my move to Pittsburgh. The Rams gave us permission to seek a trade before the draft. Two teams needed a running back: the Oilers and the Steelers. Houston was picking at No. 14. Pittsburgh was picking at No. 29 because they had just lost the Super Bowl.

Luckily, my agent also represented a college running back by the name of Eddie George. So we started negotiations with both teams, and my agent said “Where do you wanna go?” Just like I did before college, I looked at it from every angle. The hard part was that both teams had a history of great backs. Houston had Earl Campbell. Pittsburgh had Franco Harris.

The key difference was that in Pittsburgh, the fans revered the running back like no other city. Running the ball was in their blood.

I told him, “Get me to Pittsburgh.”

Before the draft, I was traded to the Steelers, and the Oilers drafted — guess who?

Eddie George.

When I got to Pittsburgh, I was quickly introduced to the concept of Steeler Football by Bill Cowher. In a nutshell, Steeler Football means this. When a linebacker is in front of you, there are two options:

1. You can go around him.

2. You can go right through him.

Guess which one we’re gonna pick?

It was perfect for me. And we won a lot of games. But we just couldn’t seal the deal. Year after year, we

2001

Kordell Stewart doesn’t get enough credit, because he lead some great teams during that era. The problem was, we got tight in the big moments. We were better than some of the teams we lost to, including the Patriots. It took me until later in life, after my career was over, to not be bitter at the teams we lost to. To look at myself and say, “You know what? We failed each other.”

As a team, we simply weren’t close enough. We weren’t playing for each other. Then this quiet kid with real long hair came to town.

2003

Troy Polamalu sat right next to me in the locker room. If you met Troy on the street you’d think, This dude is pretty quiet. Nice guy. Is he a priest? But sitting next to him every day, I got to see how intelligent and thoughtful Troy was about football.

On the field, I didn’t recognize him. He was an animal. He was not the same guy. Literally, not the same person. When we got Troy, you could feel things changing. That was the first step. The second step was when we drafted Ben Roethlisberger.

2004

We finish the season 15–1. I’m thinking, This is it. This Roethlisberger kid is the real deal. We’re gonna do it. We get to the AFC Championship Game. Who’s waiting for us? The Patriots. Again. I remember it was 10° at kickoff. We come out flat and never recover. Ballgame.

After the game, I’m sitting on the sidelines, sick to my stomach. Ben Roethlisberger comes over to me and says, “Give me one more chance. I promise I’ll get you to the Super Bowl.”

The dude was a rookie. I’m like, O.K., man. Whatever.

That Monday, I asked Coach Cowher if I could address the team.

I told my teammates that I was done. I thanked them for everything they did for me. There wasn’t a dry eye in the room.

Hines Ward was crying so hard, and unfortunately there happened to be some TV cameras nearby. He was like, “Jerome deserves to be a champion.” He was just bawling. I watched it on TV later and I’m like, Oh man. This dude is the toughest guy in the NFL and now I got him crying on national TV.

Right after the Super Bowl, I got a call. Corey Dillon had broken a rib and was going to miss the Pro Bowl. I was the first alternate. To be honest, I didn’t want to go. My daughter had just been born prematurely, and she was still in the hospital. But I talked to my wife and she said, “Look, this would be a good opportunity to end your career on a positive note. You need this as closure.”

I got on a plane to Hawaii. What I didn’t realize was that the team that loses the AFC championship coaches the AFC Pro Bowl team. So I got to the hotel, and the whole Steelers coaching staff was there.

My entire life changed during a luau. They were having a big Steelers dinner the night before the game. The Rooneys were there. All our Pro Bowlers were there. All the coaches. I’ll never forget, our linebacker Clark Haggans came up to me and said, “Man, I tell you what, it’s gonna be a real shame.…”

He just trailed off.

I said, “What’s gonna be a shame?”

Clark said, “When we play in the Super Bowl in Detroit, and you’re not out there with us.”

The light bulb went on.

“The Super Bowl is in Detroit? Damn.…”

I pictured my teammates lifting the Lombardi Trophy in my hometown. But then I also thought about my daughter, my wife … I was just really torn.

After the Pro Bowl, I went home and my wife said the magic words that made it all happen. “It’s up to you, baby.”

I called Coach Cowher.

“Alright, let’s do this.”

2005

Only problem was, I was old. That was the problem. It wasn’t being out of shape. It was being old. My body was starting to break down, and I was banged up all season. It was a race against time. I knew I couldn’t do what I used to do.

We kind of limped into the playoffs as a wild card. But Ben was just phenomenal, and we got hot. After every playoff game, Ben would hand me the game ball and say, “One step closer.” That’s how tight we were. We were finally all doing it for each other.

Ben saved my ass by making that shoestring tackle in Indianapolis in the divisional round. We were on the Colts’ two-yard line with a minute left. Up three. All I had to do was punch it in, and we were going to the AFC championship.

I get the call in the huddle. I’m like, Touchdown. Let’s do it.

Ben hands me the ball, I turn sideways to fall into the endzone, and their linebacker hits his helmet on the ball perfectly. I’m falling backwards. I see the ball in the air. And I’m thinking the only thing you can think in that moment: Oh shit.

There’s nothing I can do but watch. By the time I get up and look down field, I see Ben tackling the guy.

I was sick. They still had a chance to tie the game. When Mike Vanderjagt missed it wide right, I was like, Wheeeeeeeeew.

Ben saved me. After the game, we didn’t even talk about it. He gave me another game ball. “One step closer.”

After that, there was no stopping us.

Super Bowl XL

My business manager took my cellphone and handed me a new one as soon as I got off the plane in Detroit. The only people who had my new number were my wife and my mother. My mom handled all the tickets. The rule was: If you hadn’t come see me play in Pittsburgh before, you weren’t getting a free ticket. Luckily, the mayor of Detroit set up some big TVs in a community center for my extended family and friends.

The thing I’ll always remember about that week was the dinner my mom and dad hosted for all my teammates. We had 50 guys packed into their house. It was a feast. Like 10 or 12 cornish hens got taken down. It was that same feeling I had as a kid: It’s crowded as hell in this house, but we got a lot of love in here.

Game Day

Before the game, we had decided we were going to run out as a team. No individuals. So we’re in the tunnel, and right as we’re about to be called out, Joey Porter says to me, “JB, you lead us out there. We’ll be right behind you.”

I have the blinders on. I see all these Terrible Towels whipping around. The announcer says, “Ladies and gentlemen, the American Football Conference champion … Pittsburgh Steelers!”

I run out, arms pumping, screaming like, Aaaaaaaaaaaahhhhhhhhhhhh!

… and Joey literally held the team back.

I turn around. Nobody’s there.

I don’t know what to do.

So I just keep screaming, Aaaaaaaaaaaaahhhhhhhhhhhh!

They got me. That set the tone. We were not going to be stopped. The game was a blur. What I remember most vividly is the moment the clock hit zero, and I realized I was a champion. The feeling was indescribable. It’s funny — Chris Doleman just asked me the other day, “Which ring is more important to you: the Hall of Fame ring, or the Super Bowl ring?”

I told him, “The Super Bowl ring, and it’s not even close.”

The Super Bowl ring is what you strive your whole career for, and the vast majority of players never get one. I chased it for 13 years. I came close to chasing it for just 12.

Thank you, Clark Haggans.

When you hug your mother as a Super Bowl champion, you realize that it’s not just the culmination of your journey. It’s the culmination of our journey.

The very next year, my father passed away. For him to be able to go along for that ride — a ride that ended where it had all begun for us — that was beyond my wildest dreams. It was the culmination of his hard work, too. His hustle, his sacrifice, his two jobs, all the night classes he taught so I could have the life he always wanted for me.

He gave me his name. I tried not to screw it up.

Photo credits, from top: Courtesy Jerome Bettis (20); Detroit Free Press/Zuma Images; SI/Getty Images; Notre Dame Athletics; AP Images; Zuma Press; Getty Images (3); AP Images; Courtesy Jerome Bettis