The Ghosts of the NFL

November 22, 1992.

Jets vs Patriots.

There’s me, a defensive lineman for New York, still on the field after sustaining a serious concussion. Kyle Clifton, our middle linebacker, would call the play, and five seconds later, I would get down in my stance and have no idea what play he just called. Right before every snap, I’d have to look back at Kyle and quickly ask, “What’s the call?”

I was lost.

I couldn’t remember what was happening then, but it’s coming back to me now …

I grew up thinking that my only opportunity to make it out of my neighborhood was by taking one of the options Biggie Smalls laid out in “Things Done Changed.” You either got a wicked jump shot or you were slinging crack rock.

I had a jump shot.

After a successful college basketball career, I was in my fourth year in the NFL, and only my fifth year of playing organized football.

It was the second quarter, 3rd and long, and we were in our dime package. This meant I slid inside to defensive tackle with my man Dennis Byrd. Our defensive coordinator was Pete Carroll, who gave us the autonomy to call our own line stunts based on offensive formations. The Pats came out in doubles with the back lined up opposite me, which meant the line was sliding my way. We called a Twist, which took Dennis to his gap, eating up the guard, and I would come around him into a wide open B gap and get an easy sack … in theory.

Ball snaps, I take my plant step right, then loop back left around Dennis in the wide open B gap, except the guard is there. No problem. I figure, I’ll just swim over him and get to the quarterback. But as I’m swimming, this guard explodes on me and his helmet catches me right under the chin.

It’s Batman time for me. I’m blacked out.

The next thing I remember is sitting on the ground, going through what used to be considered the “concussion protocol.”

Where are you?

What’s the score?

What team are we playing?

On the sideline, I sat down and popped a couple of ammonia capsules. Meanwhile, the trainers and our team doctor, Elliot Pellman (a name now infamous in CTE circles), were figuring out “the severity of my injury.” I remember the trainer giving my D-Line coach the thumbs down on me, and Bill Hampton, the head equipment man, grabbing my helmet from me and taking the pads out of it.

All of the sudden, a coach shouts, “Goal Line!!!”

I was on the goal line team, so I snatched my helmet from Hamp, and ran onto the field. I had to go to work.

I was lined up on the tight end, and my assignment was to control the C gap and build a wall if the play came my way. The play did in fact come my way, and not only did a wall not get built, but I got hooked by the tackle, and was trying to fight my way through the block, to stay out of B gap. After the play, I went to the sideline, and the trainer asked if I was OK. I said yes, even though I had no idea why he was asking me.

I played in that game up until the fourth quarter, even though it was all a fog. Finally, Kyle told Pete to “get me out of there.” I watched the rest of the game and wondered what had happened to me.

Afterwards, I had an awful headache and asked for something. They gave me two Tylenols, but I dropped them on the floor and said “Tylenol 3s.” I mean, by that point I’d figured this football deal out. Your head hurting after a game? Go with the 3s.

On the plane ride back to New York, I read the stat sheet and realized I had no memory of the game I had just played in. It wasn’t until the following Thursday, that my recall started coming back and I had use of my short term memory. I had a slight headache still, but my Tylenols helped. I never thought about anything more serious being wrong, because who didn’t play hurt this late in the season? This is the NFL. You can play hurt, you just can’t play injured.

I consider myself an expert on the NFL’s past, having lived and fought through many practices and games. This was a league predicated on selling violence and big hits. I watched (sometimes horrified) at how players got bigger and faster, but largely remained ignorant of the long-term dangers of concussions. Simply put, the process usually went:

- Get your bell rung

- Sniff some smelling salts

- Get back in there

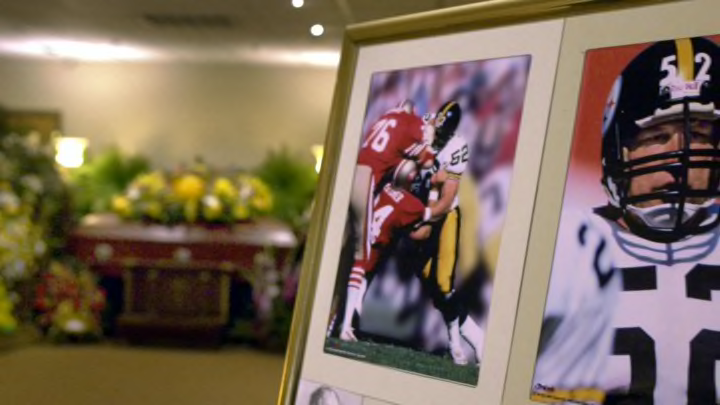

What emerged from the ghost of the NFL’s past was a Pittsburgh Steelers player named Mike Webster. It was his unusual struggles later in life and his sudden, tragic death at age 50, which started raising questions that needed answers. Then, almost out of nowhere, you have Dr. Bennet Omalu perform the autopsy that changed football. With his discovery of CTE, suddenly there was more insight into how and why we had lost so many former players too soon.

And, honestly, that’s the moment when we all started to wake up.

I truly do appreciate the game of football for the unique life lessons it can provide. But that being said, CTE is the NFL’s industrial disease. A recent study from Boston University found that 87 out of 91 former NFL players tested positive for CTE.

With Will Smith’s Concussion film coming out on Christmas Day, the NFL’s long-standing issues with head injuries have been tossed into the mainstream, and not just in football-related forums.

To the NFL’s credit, a lot has changed since the ignorant days of the past. It took some time – probably a little too much time – but things have gradually changed.

In 2010, the NFL at last made Dr. Ann McKee’s Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy at Boston University its preferred brain bank. This important step was crucial for developing more knowledge about concussions and the complications that were visible in the brains of deceased NFL players.

In 2013, the NFL created its now well-known “Concussion Protocols,” as well as the Head, Neck and Spine Committee. While the existence of these protocols was seemingly a positive first step, it’s very much a work in progress. A notable example of a failure to follow the protocols occurred earlier this season when St. Louis Rams quarterback Case Keenum continued to play after clearly sustaining a concussion.

While Keenum’s case was perhaps this season’s most obvious and publicized case of a concussed player staying in a game, this is something that has happened many times just this season.

Malcolm Jenkins of the Eagles admitted to playing with a concussion during a game this year.

Janoris Jenkins, another player on the Rams, was placed back in a game after getting “knocked out cold.”

And the Bears also said they did everything by the book after a particularly vicious hit on Jay Cutler, but many observers indicated otherwise.

Then there was the much maligned concussion lawsuit settlement that involved more than 5,000 former players and somehow inexplicably completely left out CTE. If Mike Webster, Dave Duerson and Junior Seau were alive today, they would get nothing out of the settlement.

***

In the 1950s, horse racing, baseball and boxing were the top three sports in America.

Man, how the times change.

These days it’s all about football. But unless the NFL makes a serious shift, it’s very difficult to believe that it will continue to be the most popular sports league in America. It simply won’t be. The NFL must change or the game that I love can’t survive.

To be clear, banning football from public schools is not the solution. We don’t need rash conclusions, rather science has to be at the center of the solution. The NFL was slow to accept the scientific research of Dr. Omalu, and many suffered as a result. Given this previous grave error, the league should be doing everything in its power to find a solution for CTE. But while strides have been made in some areas, there’s much to be done in others.

This is why I firmly believe that it’s far past time for the NFL to adopt a rational marijuana policy.

The attitudes surrounding marijuana are largely informed by the past. But looking towards the future, the league must embrace the potential medical benefits for its players.

There’s a compound in marijuana called cannabidiol (CBD), which has shown scientific potential to be an antioxidant and neuroprotectant for the brain. In layman’s terms, there’s a possibility that CBD can work as a sort of “helmet for the brain.”

How serious is this development? Well, the U.S. federal government has patented the technology, and is researching the potential for using cannabinoids as a treatment for CTE. To conduct said research, the government has licensed KannaLife Sciences, who I’m proud to work with directly. Dr. Omalu spent almost a year on KannaLife’s Scientific Advisory Board, where he was joined by many of the top neurologists in the country.

Among those world class scientists and supporters includes Dr. Safa Sadeghpour, one of Harvard’s top brain surgeons; Dr. Ron Tuma, one of the most credible cannabinoid-based researchers in the U.S.; and Dr. Bill Kinney, a proven innovator and scientific leader in the U.S. pharmaceutical industry.

There are a lot of very smart people who think that there’s a chance that medical marijuana might be the key to potentially preventing CTE. For this reason alone, the NFL should be doing all that it can to push this research to the forefront.

The NFL has to lead the science, and not just follow it, as Commissioner Roger Goodell likes to say.

As the ghost of my own future creeps closer every year, it’s very important to me to teach as many people as I possibly can the connection between football, concussions and the potential marijuana has to help. We’ve all been blind to the truth about how we could be protecting each other for a very long time. We’re past the days of taking a few Tylenol 3s and moving on.

The day before Thanksgiving this year, I was at my mom’s house making my world famous Hoppin’ John recipe, when I heard that CTE had been discovered in Frank Gifford.

The news made me stop in my tracks. If Frank Gifford had it, what hope is there for the rest of us? Most fans know Frank from his HOF broadcast career, and marriage to Kathie Lee Gifford. Most don’t remember that he was once out of football for 18 months after suffering a concussion following a crushing hit by Chuck Bednarik. Given how lucid and charming he was on air, it was easy to see how the public might forget that he’d suffered serious head trauma.

After I heard the news, I got on the phone with a former teammate, who said that we all probably have CTE to some degree. It’s difficult to disagree.

It was definitely upsetting news, but I’m very thankful to the Gifford family for making the findings public. They gave us a very beloved name and face to associate with this issue.

There was a lot of backlash on Tuesday, when a source told Outside the Lines that the NFL elected to renege on its agreement to help fund an ambitious study conducted by the National Institutes of Health in part because it was being lead by a neurologist who had previously been critical of them. The league denied the accusation, but it raises a larger point: Instead of hiding in the shadows, the NFL should be upfront and vocal about CTE. The chorus of people who want answers is growing louder, and we aren’t going away. I urge the league to set up a separate CTE fund to support former players and to get behind truly autonomous independent researchers who are working to find a solution to treat closed head injuries in all sports.

This Christmas, while Will Smith has us all talking about CTE around our living rooms, let’s also talk about how the U.S. government has licensed research into medical marijuana and CBD as a potential preventative measure for CTE. This is real science that can help people.

To all that watch football this holiday season, I urge you to stand by what’s right.

***

Marvin Washington is a retired 11-year NFL veteran, a Super Bowl XXXIII champion and retired players CTE/Concussion advocate. He is currently a spokesman and advisory board member for KannaLife Sciences. You can get involved with CTE awareness and research for a cure at www.treatCTE.org.