Restoration

After my surgery, back in my room, my wife Sara and I looked at each other.

“Alright, do you want to see it?”

We took the blankets off my leg — the part of it that was still there. I try to keep things simple, and not overanalyze. Half of my left leg was gone. I actually did okay with that part. But the craziest feeling was when I picked up my leg and there was no weight to it. Physically, that felt extremely weird.

It kind of freaked me out.

My accident was in December 2008. I was racing snocross in Ironwood, Michigan, and after a bad start had worked my way up to sixth. I needed to make a move. As I came through a rough downhill section I got off balance. My snowmobile started shifting side to side and I wasn’t able to hang on. When I hit the ground, my knee hyperextended 180 degrees, with my lower leg ending up on my chest. When the medical team reached me and opened my pants leg, blood gushed out. The accident severed the main nerve and artery supplying my lower leg, causing severe complications with my health including major circulation problems. From the moment of the accident through several surgeries at the hospital in Duluth, I used 42 units of blood. The reality was that the best way for me to go forward was to amputate at the mid-thigh.

In those first 24 hours after the surgery, the pain was excruciating and completely overwhelmed my body and mind. Over the following two months, it remained constant. “Phantom pain” is what they call it — basically, your nerves aren’t sure what signals to send to your brain, so they just send pain. Sometimes it was a pins-and-needles throbbing, other times it felt like lightning bolts shooting through my leg. Everything below my thigh was gone, but it felt like my foot was still there. We tried all kinds of different medications to get a handle on it, and it was really frustrating because nobody could give a straight answer on how long it would last. Some of the doctors said it would last forever. I was worried this was going to be my new life.

Then I got my first prosthesis. Putting weight on my leg and having feeling there, the nerve pain started to dissipate. I learned how to walk again, but figured I would have to sit back and get an everyday office job. I had been a professional snocross rider, racing motocross in the offseason, and assumed my competition days were over for sure.

That’s what I thought, at least.

In the spring of 2009, I learned that X Games was adding an adaptive Supercross race. There were one-legged and even paraplegic dirt bike riders still competing against each other. That motivated me. It gave me a new goal in life — to ride and race my dirt bike again. It’s what made me feel normal. But I had to figure out the right equipment to make that happen. I’d tried riding my snowmobile with an everyday prosthetic leg, and it didn’t work. Its knee was a basic hinge that just flopped around and didn’t give me any help whatsoever.

I needed a durable prosthetic with a full 135 degrees of motion, which is the natural range for a knee. It needed to provide resistance, so I could stand up and sit down, absorbing impact on jumps without having to make adjustments on the fly. Luckily, I had the perfect combination of experiences for the situation, starting with a background in metal fabrication. Growing up, I was always building, cutting, and welding. I was a shop guy, a problem solver. As a professional athlete, I understood how muscles and bone structure impacted certain movements.

My mind shifted into overdrive. Mechanically, one of my favorite things about racing snowmobiles was working on suspensions. Now I was building a suspension component for my leg. I knew I wanted to design the knee system around a FOX mountain bike shock with compressed air in it. Basically, that component would take the place of my quadriceps muscle.

Five months after my injury, I had a prototype built, and took it to the qualifier for the X Games. Almost everyone was riding in everyday prosthetic equipment. Not surprisingly, I got a lot of questions about my leg. A lot of the amputees said they thought it was cool, but I could see the wheels turning. It was big and bulky, and I knew a few thought it was a hunk of junk. Then they saw me ride with it, and there was a heck of a lot more interest. I did a second revision for Summer X Games, and ended up with a silver medal that was good as gold. Before my accident, I had competed in six Winter X Games events as a pro, and it was incredibly powerful for me emotionally to be back. (To date, I’ve won a total of four gold medals in Winter X Games Adaptive Snocross, plus two golds and a silver the summer, for X Games Adaptive Moto X.)

Still, I wasn’t a pro athlete anymore. I understood from the start I needed a Plan B, and since designing that prototype in 2009, my mind had been spinning with possibilities. At every competition, interest in my custom knee grew. I saw how it could help athletes like me, people who wanted to get active and get back to their passion after losing part of their leg.

I kept refining my knee. Soon it had a name, the Moto Knee. In late 2009, I developed the first iterations of the Versa Foot, which had a more natural and controlled flex than a typical prosthetic foot. In 2010, I started my company, Biodapt, to produce them. It was the beginning of a real business.

But there was another group ready to benefit that I hadn’t considered.

At Winter X in 2011, I was approached by a group called Adaptive Action Sports, based out of Colorado. They were a huge part of of getting adaptive sports into X Games. They told me about a snowboarder named Keith Deutsch. A retired U.S. Army sergeant, Keith lost his leg in 2003 when his vehicle was hit with a rocket propelled grenade while serving in Iraq. Later that spring, Keith and I met up to test the Moto Knee. He tried it on, and 100 yards off the chairlift, he was able to carve and ollie, jump and spin. Meeting him down at the bottom, Keith ran over, gave me a huge high-five, and told me he hadn’t boarded that well since he had two good legs.

It was an extremely powerful moment for me, to see somebody else benefit from something I’d developed. Keith became Biodapt’s first client. Today, about half the people wearing Moto Knees and Versa Foots are military veterans.

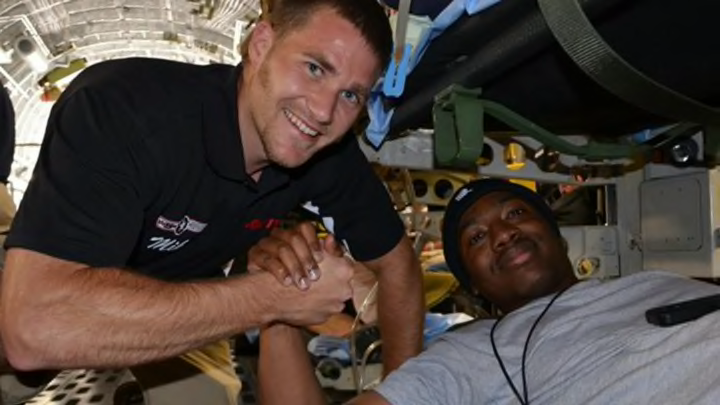

In 2011, I went on a 12-day tour to the Middle East with a group called America 300. It was me and Levi LaVallee, one of the world’s best freestyle and snocross riders. Our first stop, though, was actually in Germany at the hospital where wounded soldiers are staged right out of the battlefield, including some amputees that had just lost their legs. Some didn’t want to talk to anybody. But when we were able to get a conversation going, and I could share my story as a fellow amputee, there was a connection. I was able to tell them it could get better. It’s not the end of the road. It’ll suck for a while, and it will be hard.

But it’s not the end.

I’d later work with a vet who had lost both legs (at different levels, which makes things more complicated), and most of one arm in an explosion. He definitely had a challenge in front of him learning to snowboard, but getting down the hill wasn’t his toughest problem; It was figuring out how to maneuver on and off the chairlift, getting in and out of his bindings, and then standing up. Most people don’t think twice about simple movements, but when you don’t have both ankles, a knee, or part of an arm, it makes things extremely difficult.

Over a couple of years, I’ve watched as determination and patience allowed him to navigate these challenges. He’s able to ride most of the runs on the mountain. Yes, he takes his time and has to think carefully about finding the best routes that work for him, but it’s incredible to see the progression, and how much enjoyment he got from snowboarding. There have been times with him, and other vets like him, where I honestly thought they would get physically and mentally exhausted before they learned to ride. But most are true warriors who don’t give up until they accomplished their goal.

While my physical loss might be similar — we’re all amputees — I don’t want to compare my experience to theirs. I gave to my sport, they gave to their country. Still, I’ve learned that there are parallels in our experience. The hardest part for me, even seven years after my accident, is accepting that I can’t compete at the highest level anymore. My mind still knows exactly what it needs to do to get my machine to work at a top level, but my body can’t keep up with my mind. I still occasionally have those thoughts.

You’d think I’d be over it by now. I’m close … but not that close.

A lot of these guys loved being in the military. That was their job, one they chose. They wanted to be the best soldiers they could be, and many I’ve met would go back in a heartbeat if they physically could.

I was 27 years old when I lost my leg. Many of the servicemen I’ve worked with are even younger. Like many professional athletes, these are people with a strong drive and focus. They’re used to being active. Many are adrenaline junkies, like me. They want to continue doing things they enjoy and need equipment to help them move forward in life.

That’s where I can come in. I know what it felt like the first time I put on a prototype knee that let me feel like myself again. To be able to help others do the same is amazing. You see their faces light up. I’m going to get into the gym again. I’m going to snowboard. I’m going to lift weights, or do my CrossFit. Get on my motorcycle. Get on my horse.

That moment where they realize a whole new door has opened, it’s priceless.

We owe so much to our military men and women. They join for different reasons, but all make the choice to serve our country, and keep it strong and safe. I’ve learned a lot in the process, and wish more Americans understood the sacrifices they have made. I never expected to be in a position like this, to be able to improve the lives of men and women who are willing to volunteer for something bigger than themselves.

But I’m incredibly thankful that I can.

Mike Schultz is a seven-time X Games medallist and the founder of Biodapt. He has donated time and expertise to military assistance groups including Wounded Warrior Project, Vail Veterans Program, and American300. Now a member of the US Paralympic Team in snowboarding, he hopes to qualify for the 2018 Paralympic Games in boardercross.