From the Ground Up

It’s funny, I still feel like a rookie.

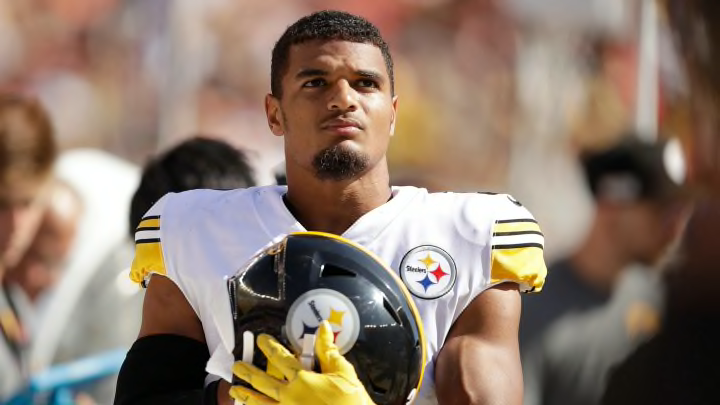

When I was traded to the Steelers last September, everything was so fresh. New team. New atmosphere. New culture. And I remember thinking what a great opportunity I had in front of me. So when I first arrived, I wasn’t concerned with getting to know my new city, or even finding a place to live. The team put me up in a hotel, and when I first checked in I was like, “Just give me the playbook.”

Then I went to work.

I stayed in that hotel for a month because I was on a mission to learn the playbook and put myself in a position to succeed. To carve a path for myself.

To make it my new home.

I’m not shy about saying that I want to be one of the greats to play this game, and Pittsburgh is an incredible place to do that. But I know very well that in this league — and in life — nothing is given. Everything is earned.

And even then, what you’ve earned can be taken from you at any moment. I learned that when I was in high school.

The storm hit during the night. I slept through it, for the most part, but the winds and the sound of the chaos outside kept waking me up. We don’t get a lot of hurricanes in New Jersey. I mean, it happens, but it’s not something that’s on our radar every summer like in Florida, Louisiana and those Gulf Coast states. I’m a Jersey boy, born and raised in Old Bridge, about 45 minutes south of New York City. And before that year, 2011, I can’t remember a hurricane ever making its way up to us.

But Hurricane Irene left its mark.

The morning after the storm, my dad and I went outside and saw the damage — or at least the start of it. Trees had been blown over, their roots pulled up out of the ground. People’s sheds had been torn apart or flipped over. Cars were all banged up and there was debris everywhere.

I remember thinking it was pretty bad … but that it could have been a lot worse. We got lucky.

Then I went around to the backyard to see what the damage was like back there and I saw water leaking through a crack in the fence. We had one of those tall, white plastic fences, and it had split in one spot and water was pouring through. I sloshed through the wet grass and pulled myself up onto the fence to look over and see what was on the other side.

I remember thinking it was pretty bad ... but that it could have been a lot worse. We got lucky.

The whole neighborhood was flooded. Cars and houses were under at least a few feet of water. We lived a couple of streets away from a small river, and it had overflowed, engulfing the entire block behind our house, and it was still rising.

Our street was next.

I ran inside and told everybody what I had seen, then my sister Destiny and I started getting as much stuff as we could out of the basement before it flooded. Trophies, photos, electronics — anything that was important to us or would be expensive to replace. My dad and I got the furniture — the heavy stuff — from the living room. We took everything we could up to the second floor because we didn’t know if the first floor would be safe from the flooding. We knew the water was coming. We just didn’t know how soon, or how much.

I was standing at the top of the basement stairs when the fence outside finally gave way and collapsed. I heard the boom when it came down, and then I heard the water rushing in. It was a loud rumble, like a packed stadium of fans all stomping their feet. As the basement filled with water, there was this big flash — a giant spark — and the power went out.

I couldn’t believe how fast the basement filled up. Destiny and I sprinted out of there, and just as the water rose to the first floor, the fire department showed up and told us we had to evacuate because the water was still coming and they didn’t know how bad it was going to get.

My parents, my three sisters and I spent a day or two at a shelter until the flooding finally subsided and we were allowed to go back to our house.

But when we got there it didn’t look nearly the same as when we had left it.

From the street, it looked like the right side of the house was sagging, like it was sinking into the ground. I remember walking up the front steps and seeing the orange piece of paper on the door saying that the property was unsafe to live in. It was surreal, like I was in a movie or something. I walked inside and my feet splashed on the floor. There were still big pools of water. It smelled nasty, like mold, and I could see the flood line where the water had risen to, maybe halfway up to my knees. I opened the basement door and all I could see was dirt. It was an old house, and the red-brick foundation had collapsed from the weight of all the water. The whole side of the basement had caved in and dirt had poured in. The loose dirt was the only thing holding up that whole side of the house.

Then I went to my bedroom. It was on the first floor and it was still flooded with a couple of inches of water. My clothes were floating on the floor. I pretty much lost everything.

The toughest part was watching my parents go through the house. You have to understand, this house was very important to them. My parents were really young when my sister and I were born, and they had bounced around from apartment to apartment for a long time — sometimes because they couldn’t afford it, other times because they’d been kicked out for stupid reasons by a crazy landlord. They’d made it a point to work two or three jobs at a time so they could save up and buy their own home — someplace permanent that they could call their own. That hard work paid off, and they bought this house.

Now, that little orange piece of paper on the door was telling them they couldn’t even live there anymore.

But still, we couldn’t help but feel lucky. A lot of people lost their homes that day.

Ours was at least salvageable.

My family and I moved into my grandmother’s house. The six of us packed into her tiny basement. I eventually went to stay at my football coach’s house for a while, and some nights I would sleep over at a teammate’s house. But I spent most nights at my grandmother’s. I was a freshman in high school at the time, and the school year — and the football season — had just started when the storm hit. So at 14 years old, I was balancing school, football, and helping my family rebuild our home.

We had no choice but to rebuild it ourselves. We had nowhere else to go. Our house wasn’t in a flood zone, so we didn’t have flood insurance. My parents took out loans to pay for the foundation work.

The rest, we pretty much did ourselves.

I was balancing school, football, and helping my family rebuild our home. We had no choice but to rebuild it ourselves. We had nowhere else to go.

I would go to school all day, then football practice, and then on nights and weekends, I would work on the house with my dad. When we didn’t go to the house, I would work on trucks with him. He was a diesel mechanic, and just before the storm hit, he had lost his job, so he was working side jobs to make money. He had me out in the street greasing up 18-wheelers. We changed out transmissions — these things were huge and heavy and I’d have to hold one up on a jack, aligning it just right so my dad could bolt it in. He had me under the hood, on the ground, under the truck — wherever he needed me.

It was dirty work, man, but I loved it. Working on a truck when you’re 14 years old really makes you feel like a man. And at that time, that’s what my parents needed me to be.

But they also wanted me to still be a kid.

While we were rebuilding our home, I was going to St. Peter’s Prep, a private school. We had to wear uniforms — a polo and khakis with dress shoes — which we had to pay for, but I had lost all mine in the flood. My parents were trying to rebuild a house and put food on the table and I didn’t want to ask them for money, so I would dig through the lost and found at school, trying to find clothes that would fit me. If I found something, I’d wait a day to see if anybody claimed it. If they didn’t, I’d snag it.

Money was so tight that some weeks that my parents couldn’t even afford my tuition. Somebody from the office would literally come and pull me out of class and tell me I couldn’t be there because my parents hadn’t paid.

I felt selfish — guilty that money that could be spent on our house and our family was going to my schooling. I even told my parents that I would quit football and get a job so I could help the family. But they told me no, they would handle it. For me, school and football would come first.

Rebuilding the house was not as fun as working on cars. But it had to be done. I was tearing walls down, hanging sheetrock, doing woodwork, laying tile — the whole shebang. It took us about a year to get the house back to the point where we could move back in, and then we basically lived in a construction zone until everything was finished. All in all, it took almost three years to finish the house. But we all chipped in.

Together, we rebuilt our home.

It’s easy to say now, but I’m thankful for that whole experience because it forced me to grow up. It tested me. It gave me perspective. It prepared me for what came next. I had always had a good work ethic just from watching my parents. They instilled that in me. But without the experience of having to balance school, football, and working with my dad on trucks and rebuilding our home, I don’t think I would have been as prepared for success at Alabama, where they demand a lot of you. I wouldn’t have been as ready for the pros, either.

And I wouldn’t be as ready as I am now to take advantage of this opportunity in Pittsburgh.

After about a month of living in the team hotel, I finally had to get out of there. Not that there was anything wrong with it, just that … it was a hotel, you know? It wasn’t homey. I had learned the playbook and was getting more comfortable on the field, but I needed to be comfortable off the field, too. I needed my own spot. So I got an apartment. Then, come spring, I told myself I would look for a house and get out and learn what my new city is all about.

Then COVID happened.

I quarantined with my family in South Florida. They had moved down there with me when I got drafted. And if you haven’t learned this already from reading this, family is very important to me. So quarantining with them this off-season was a great opportunity because we spent a lot of quality time just being with each other, going on bike rides, watching movies, acting silly, and annoying each other. And it was time I otherwise wouldn’t have had with them, because football can be all-consuming. So I’m very grateful that we got to spend that time together.

When I got to Pittsburgh, I was welcomed with open arms. They welcomed me into their family. They made me feel at home.

My family probably won’t move up to Pittsburgh with me. They’re loving life down in South Florida. But when I got to Pittsburgh, I was welcomed with open arms. They welcomed me into their family. They made me feel at home.

I haven’t had the chance to get out and really experience Pittsburgh yet. I’m still excited to do that. But I was able to get out and look around for a home. I had my parents on FaceTime while I was checking out some spots this summer. But if there’s one thing I learned from my first experience of buying a home down in Miami, it’s that there’s no need to rush. I’m going to take my time and find the place that’s right for me.

In the meantime, I’m just going to keep working. I had a good season last year, but I understand that greatness isn’t defined by one play, one game, or one season. It’s repetitive. It’s habitual. You have to be consistently great. That’s what I’m trying to do.

And if I can do that, then I guess I’ll have the best of both worlds: I’ll have my family at my home down in South Florida, and I’ll have my football family up here at my new home in Pittsburgh. And that’s something worth working for. Because to me, that’s what home is all about. Family. A house is a structure, and those structures make up a community. But it’s the people that make a house — and a city — home.