Scar Tissue

When I woke up that morning in Fort Myers, Florida, I was sitting all alone in my underwear.

No shoes. No shirt. No pants. Just underwear.

Also, I was somehow behind the wheel of a parked car that didn’t belong to me.

And there was broken glass everywhere.

What the hell is this?

I rubbed my face and scratched the back of my head, and then I looked to my left and noticed that the driver’s-side window had been smashed in.

What the fuck?

Beyond what I could see with my own two eyes in that moment, I had no clue what was going on. Or what had happened. All I could remember was taking a bunch of pills the night before, and then it’s just … me sitting there in my underwear in the parking lot of an apartment complex.

So almost everything that I tell you from here on is what the cops told me.

This was the spring of 2012, and I was with the Red Sox at the time. I had been living in an apartment down in Fort Myers while participating in extended spring training to rehab a back injury. And on that night, after taking those pills, and without even knowing it, I apparently went into the fridge, took everything out, and piled all my food on the counter — cold cuts, eggs, steak, ice cream, everything.

After that — or hell, maybe before, I don’t know — I stabbed the television with a knife, leaving a huge gash in the screen.

Why?

Good question!

Who the hell knows why? is the only answer I have for you.

Apparently I also took everything that was in the shower and on the bathroom counter and threw that stuff in the kitchen sink. The apartment ended up looking like a tornado had hit it.

And all that had taken place before the whole underwear thing even happened.

So anyway, there I am sitting half-naked in the driver’s seat, covered with broken glass, clutching the steering wheel of a car I didn’t recognize.

As things get less foggy, I notice a few paramedics and a couple of police officers standing around. It turns out that the guy whose car I’d busted into actually called the ambulance instead of the cops because he saw that I wasn’t a threat.

Dude probably thought I was dead.

And, man, those paramedics and cops … I can’t imagine what they must have been thinking about me. It must’ve been a pretty crazy thing to see — kind of weird and confusing at the same time. But eventually they get me into the back of an ambulance, and the whole time I’m sitting there I’m trying to piece together what had happened the night before.

I can’t remember a thing.

Even after they drive me to the hospital, while I’m being looked at by a doctor, after all that time had passed, I’m still super groggy from all the pills. I’m fading in and out.

Then at one point a trainer for the Red Sox walks in. So now I’m not only in a daze, but I’m also really nervous and stressed about the team finding out what happened. The hospital had done a drug screen, but I told the nurses that I would not allow it to be released to the Sox. So even though it was pretty clear to anyone who saw me that morning what had gone on, the team never had specific proof of what I had taken. Or how much.

They didn’t know.

And, honestly, neither did I.

When the drug test came back, it showed that I had mixed a bunch of Percocet with some Ambien that night.

Then I stabbed a TV and apparently went wild for a few hours without even knowing it.

To this day, because my representatives were able to keep the whole thing out of the news, only a few people who were on the scene at my old apartment complex or working in the hospital that morning even know about it. This is the first time I’ve ever talked about this. And thinking back on all the stuff I did that night, and how I didn’t remember doing any of it, I definitely find it all to be super scary.

But the crazy thing is that, in a lot of ways, it’s not even the scariest thing about what I’ve been through over the past decade. I mean, it’s up there. Top five, maybe. But I’ve lived through some stuff. I’ve got some stories.

And the story of how I ended up at a point in my life where I was half-naked and passed out in someone else’s car is one that actually began a year or so earlier, when I had just signed with the Red Sox as a free agent and threw an extremely unfortunate pitch after taking the hill one night in the Bronx.

I came over to Boston before the 2011 season, after serving as the White Sox closer for five years. And man, 2011, I mean … that was an absolutely insane year for me. Just totally, totally crazy.

I pitched pretty well early on in the season. Then I suffered a bicep strain that sent me to the DL, and I just kept trying to gut it out and keep pitching after that. So we’re in New York playing the Yankees one night in early June, and I’m out in the bullpen trying to get loose, but nothing’s working. It almost feels like every throw is the first toss on the very first morning of spring training. I can immediately tell something isn’t right, but I talk myself into thinking it will be fine.

My body clearly has different ideas.

I get the call from the bullpen to face Jorge Posada late in the game. He takes my first two pitches for balls before I get him to swing and miss on a heater. Then, on that fourth pitch, I throw him another four-seam fastball, and as soon as the ball leaves my hand I feel this really odd sensation. It’s hard to describe, but it’s almost like a spoon had been shoved into my back — like someone is trying to dig a hole in me, not with a knife, but with a spoon. And the pain extends to underneath my armpit.

I immediately come out of the game. I know something is wrong.

It’s almost like a spoon had been shoved into my back — like someone is trying to dig a hole in me, not with a knife, but with a spoon.

So I go down into the tunnel, and the team doctor for the Yankees meets me there. But no one really has any sense of exactly what is going on. The pain continued to linger after that, to the point where I even needed to wait a few days before I felt good enough to go in and get a full set of images done.

From there I went to see a bunch of doctors and experts to try to get some certainty. But none of them could determine what was wrong. We were doing scans, and getting all types of images, but nothing was pinpointing the issue. Everyone just kept telling me they weren’t sure what to make of it.

I was in pain, but no one could tell me why. And after a while it started to drive me nuts. It was playing with my mind.

I remember I kept trying to tell myself to be strong and hang in there. It was like, You’re a fucking closer, Bobby. Tough as nails. You can handle this. But everything about what was happening went against my nature.

As a pitcher, and especially as a closer, I’d always prided myself on being locked in and focused and handling my business. No challenge was too big, and when I came into a game every single fiber of my being — every movement, every thought … everything — was solely focused on getting the job done. I was in total control. Either I came through or I didn’t, but there was never any doubt as to who was in command.

With this injury, though, it was the opposite of that. I felt helpless — like I had absolutely no say in anything, and that nothing I did would help. It seemed like everything I tried, and every opinion I got, only resulted in more uncertainty. It was maddening.

That’s when I first started taking the pain pills.

It was actually Tim Wakefield who figured out what was up with my injury.

We were sitting in the trainer’s room one morning and he asked me if they’d done any spinal images, because he’d experienced something like what I was describing, and it had ended up being a problem with his back.

So I went and got a special MRI of my spinal cord, and that’s when I finally got some clarity. It turned out that I had these spurs on my spine that were sitting on nerves and calcifying tendons. I was told that the best way forward was to have surgery to clean everything up and to relieve the pressure on my nerves.

But, of course, it couldn’t just be that simple.

At that point it was like everything that could go wrong did. In the course of flying back and forth to see different doctors and trainers, I developed a blood clot that had moved up to my lung, a pulmonary embolism. Those things can kill you. We had to delay the back surgery. Then, a few weeks later, I came down with colitis and started having problems with my stomach, so I had to be hospitalized for that, too.

In that one season, 2011, it was: bicep tear, back injury, pulmonary embolism, colitis.

Then came the surgery.

In that one season, 2011, it was: bicep tear, back injury, pulmonary embolism, colitis. Then came the surgery.

All the preoperation doctor’s visits in Boston had me feeling at ease about how things would go.

I remember the surgeon telling me that what we were looking at wasn’t a terribly complicated procedure — that I had nothing to worry about, and that I’d be back on the field in no time. Everything seemed set up for success.

No big deal.

This was in December, and, going in, I felt like I’d be ready to pitch again by the end of spring training.

When operation day rolled around, everything seemed to proceed as planned. After I woke up from the anesthesia, I asked how things had gone, and the nurses all said things went great. So I didn’t think twice. It was just like, Perfect! Let’s go! On to next season.

But then, a few days after leaving the hospital, I’m at my hotel in downtown Boston and something seems off. I’d been told that there would only be a small incision in my back — three or four inches — and minimal muscle damage. But it felt like my whole back was bandaged. I kept looking at it in the mirror and taking pictures of the bandages with my phone to help me see what everything looked like. And what I saw didn’t make sense to me. It seemed weird that my entire back was gauzed up and covered in tape.

When our trainer stopped by to change the bandages, I asked him to take a few photos of the scar, and I remember seeing those images and being absolutely blown away.

This was no three- or four-inch scar. It was more than a foot long — like about 15 inches or so. And nothing about that incision seemed minor. There was no way you could look at a scar like that and think, No big deal.

But you can’t reverse a surgery, you know what I mean? You can’t delete a scar. All I could do was fly home and try to rest up.

So then I’m back home in Arizona a few days later, parked on the couch watching some TV while my children are out playing by the pool. I reach down to grab the remote and I suddenly feel a big cup of water being dumped down my back by one of the kids.

It’s cold, so I’m kind of shocked by it — you know how you tend to cringe and tense up when someone catches you off guard like that — and my shirt is soaked. I immediately turn my head to see who did it, and.…

There’s no one there.

The kids are all still out by the pool. I can see them out there playing.

I have no idea what’s happened, or what the fluid running down my back is, but I just feel all wet and gross back there. So I call my wife over and she unwraps the bandages and … just kind of gasps.

“Bobby … oh my God. You gotta see this.”

She snapped some pictures with her phone and then showed me that the bottom of my incision, about three-fourths of an inch of it, had burst open. That’s where the fluid was coming from. And it was just flowing out, too. It was constant — almost like a faucet that had been opened just a tiny, little bit. When we were able to get a look, we saw that it wasn’t blood. It was this weird clear liquid.

Neither of us knew what to do at that point. We couldn’t get ahold of the doctor who’d performed the surgery, so we just kept bandaging me up. But we needed to change the dressing on my incision a bunch of times because it just wouldn’t stop leaking fluid. I had to wake up three or four times that night to switch out the gauze, and the next morning I decided I needed to get looked at by a doctor.

I drove over to one of those little medical clinics they have everywhere now, and as soon as the doctor in that place saw me, he took immediate action. It was like, “I’m calling the hospital right now. Go home and pack some things, and then I need you to get to the emergency room….

“Mr. Jenks … you’re leaking spinal fluid.”

When I got back to the house, it was like a wave hit me. All of a sudden, my head felt like it was split wide open. Like someone had put a coconut in a vice and cracked it.

It felt like my head was going to blow up and separate from my body.

“Son,” the doctor said after I regained consciousness at the hospital, “you’re lucky to be alive.”

After I arrived at the emergency room they had to put me under anesthesia to get a set of images done of my spine, and literally the first thing I heard when I woke up was a doctor telling me that I had almost died.

I was still a little groggy from the gas, so I didn’t really know what he was talking about. But then he gave me a complete breakdown of everything that had happened, starting from the time when they put me under. It turned out that they’d had to perform an emergency surgery on my back to stop the spinal fluid from leaking. And when the doctor went in to perform that procedure, he was able to see the results of the operation that had been done the previous week back in Boston.

My surgeon back on the East Coast was supposed to decompress two levels of my spine, and my insurance company had been charged for both elements of the procedure. But now I was being told by this new doctor that only one level had been decompressed, and that the second part of the surgery was never fully completed. To make matters worse, he said that the surgeon in Boston, in using the tool that shaves bone spurs, had left a jagged point, a bony spike, in my body. And that was what had ended up puncturing the membrane around my spinal cord — something called the dural sac — in two different places. The doctor in Arizona told me that while he had been in there doing this new procedure, he’d found a spike that was actually still embedded in my dural sac — that a week earlier I’d been sewn up with this thing still inside me.

I was hearing about all this for the first time, so I was just completely surprised and blown away by it all, and then.…

The doctor kept going.

He told me that I’d developed an infection in my back that had traveled up through my body and nearly reached my brain stem. I was going to have to administer antibiotics to myself intravenously every day for three months.

It just kept getting worse and worse, and everything was compounded by the fact that we still weren’t able to get ahold of the doctor back in Boston. I was calling, I had my agent calling, the doctors in Arizona were calling, we were emailing — no one could get through.

Up to then, I was still confident about making a return to the game, but the more I heard, the more it seemed like we’d maybe gone past a point where I’d ever be the same as a pitcher. Because now a second surgery had taken place, and the incision had to be reopened, and additional scar tissue would surely build up. Not to mention the fact that this infection had been eating away at my back, causing more decay and degeneration in the areas where these surgeries happened.

When I asked the doctor if I was ever going to be able to pitch again, he was straight-up with me. He didn’t sugarcoat anything.

“I honestly don’t know if that’s gonna be possible, Bobby.”

In Februrary 2012, three months after the surgery to stop the spinal fluid from leaking and repair my back, I flew down to Florida for spring training with the Sox. I wasn’t going to be able to pitch at that point, but at the very least I could continue my recovery while surrounded by team doctors and trainers.

It was actually a really smart plan. And it would’ve probably worked out great if.…

I hadn’t already become addicted to painkillers.

I’d been taking the pills ever since I hurt my back the previous season. Percocet mainly. And when I started out, I was taking them for the right reason — to manage pain. But the longer I took them, the more my body built up a tolerance. I had to take more and more to get results. So I found this doctor, a guy at one of those pill mill places. I’d send him a check, and he’d ship me as many pills as I wanted.

In my head, I didn’t think I was an addict. I felt like I was still in control of everything. But before reporting to Fort Myers, I decided to check myself into a drug detox place for a week just to try and get off the pills and clear out all the toxins from my system. And….

It wasn’t pretty.

Cold sweats. Convulsions. I couldn’t sleep at night. I had the shakes. I honestly didn’t think I was going to make it through that week. But I stuck it out and by the time I reported to camp with the Red Sox, I was totally clean and feeling … I won’t say good, but definitely better than I had in awhile.

And I remember the first day I was down in Fort Myers went great. It was awesome.

On the second day.…

I called up that doctor at the pill mill.

In my head, I didn’t think I was an addict.

I still remember sitting there with the phone in my hand, about to dial, having this conversation with myself. It was like, O.K., if you’re gonna do this, it has to be different this time, Bobby. You can only take so many. Just a few at night. That’s it.

By the end of the week, I was taking 50 or 60 pills a day.

That spring … I don’t know. I was there but … I wasn’t really all there. You know what I mean? I was so deep into my addiction — and so depressed — that I stopped wanting to do anything in life other than sit around, down some pills, and just … drift off.

I’m showing up to the field. I’m doing my physical therapy. I’m putting in the face time. But … I don’t want to be there. I’d go right back to my hotel after my day of treatment was over, turn the lights off, pop a bunch of pills, and then lay there and veg out until I had to do it all over again the next day. That was my routine. I didn’t go anywhere. Didn’t do anything.

When I did need to go out for any reason, bad things happened.

One night, about a month or so into camp, I had to run out to the store, and I took some Percocet thinking I’d have time to get back before they kicked in.

I was wrong.

When the officers pulled me over, I was honest with them. They wanted me to do a sobriety test, and I came right out and told them I was messed up on pills.

“I’m going to fail it,” I said. “I’m intoxicated.”

On the way to the police station, they showed me a dash-cam video of how I’d been driving. It was terrifying. I was swerving in and out of lanes the entire time. I could’ve easily killed someone. I was just completely out of it. As soon as those pills hit, I was just totally gone.

I could’ve easily killed someone. I was just completely out of it. As soon as those pills hit, I was just totally gone.

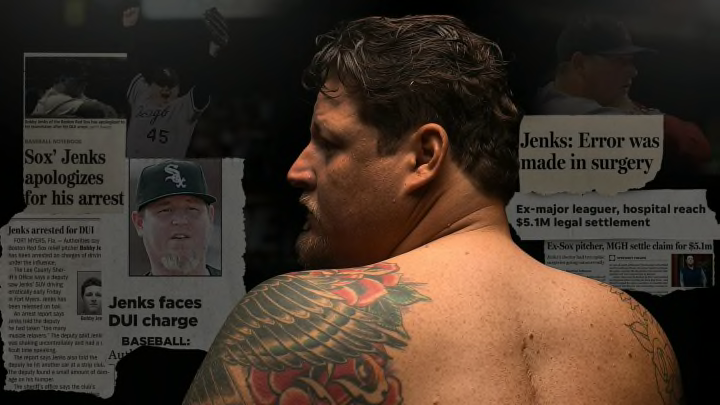

The next day, when the papers came out, the big news was that I had gotten busted for DUI. And I’m pretty sure most people just saw it for what it seemed to be: a baseball player who had downed one too many during the evening and then tried to drive himself home.

But that was so far from the big picture of what was going on with me.

A few weeks later is when that insane incident at my apartment complex happened. And after that mess went down I decided to go back home to Arizona to be with my family. It didn’t take long for shit to hit the fan.

It’s May 2012 at this point. I’m sitting in my bedroom by myself, and my agent walks in. He’s trying to coax me into the living room.

I immediately know something’s up.

He just keeps coming up with these weird reasons why I need to follow him into the living room. And after a few minutes I give in.

Before I even enter that room, I know what’s gonna happen.

In addition to my agent, it’s my wife at the time, my in-laws, and two addiction counselors. It’s a full-on intervention.

They tell me why they’re all there, and then they go through the full process of … We love you, and We’re worried about you. They each read me their own letters, telling me how special I am and how I am no longer myself, and begging for me to get help.

It was all honestly very heartwarming. And kind. It was one of the nicest things anyone has ever done for me.

But, you know what?

I still didn’t want to go to fucking rehab.

It wasn’t one of those deals where you see yourself reflected back to you by the people you love, and then you have this epiphany, and you go get help.

No.

I was a hard-ass about it. Big time. But I ended up giving in and doing 30 days of inpatient rehab.

It was all-consuming, too. It was one-on-one therapy, group discussions, information sessions. And as much as I fought going, I have to admit that I learned a ton about myself. I also was finally able to admit that I am an alcoholic and addict — that I was addicted to pain pills.

And when the 30 days were up, I felt like I still needed more help, so I decided to do an additional 30 days of treatment at another rehab facility. I was going through it, man.

And right around that time, my wife filed for divorce.

So now I’m dealing with a divorce while at the same time trying to get sober.

2012, man … rough year.

All the while, though, I still felt like I’d be able to make it back to the bigs. I took solace in that. I kept telling myself, If you can overcome everything that’s happened with these injuries and your addiction, you can do anything.

So I genuinely believed.

But the back pain never really fully went away.

After about another full year of dealing with it, and hoping it would disappear, I had some scans done, and they showed that due to all the damage and deterioration from the surgeries, my spine was in an extremely weak state. The specialist I was seeing told me that in order to try to fix it, he’d need to go back in and add some plates and screws to the regions that had been worked on the first two times.

It would mean the end of my career.

No maybes. This surgery would make it so that I’d never be able to pitch again.

So I had to decide whether to have surgery to try and live a normal pain-free life, or basically go through a ton of physical therapy and additional pain to try to get my back healthy enough to where I could take another shot at just trying to pitch again.

And as much as I’ve always loved baseball, it really wasn’t a close call.

I couldn’t live with the amount of pain that I was experiencing. And I was constantly worried that in trying to fight through that pain, I might slip back into my addiction again.

When I made the decision, I’d been sober for almost 11 months.

I had no desire to go back to where I’d been.

I couldn’t live with the amount of pain that I was experiencing. And I was constantly worried that in trying to fight through that pain, I might slip back into my addiction again.

The depression that came along with that final surgery in 2013 hit me hard.

And it stuck around, too. Like for years.

It wasn’t just that I had retired, that I wasn’t going to play anymore. Everyone retires. That’s part of life. You can’t play this game forever. We all know that the moment we sign our first professional contract.

But this wasn’t your typical retirement.

I didn’t decide to stop playing baseball. I had the game taken away from me because of a botched back surgery in Boston that was supposed to be no big deal — because a level of care and professional expertise that I trusted to be present … was not there.

It wasn’t until I filed a malpractice lawsuit, and did some digging, that I found out what exactly had gone so very wrong.

The more my attorneys and I dug into that initial surgery on my spine, the more things seemed out of whack. When we eventually put all the pieces together, what we discovered was jaw-dropping.

In short, there’s this thing now going on at some hospitals that’s referred to as concurrent surgeries, and it’s straight up evil. It’s basically one doctor overseeing two surgeries … at the same time.

Yes … you read that right. One doctor. Doing two surgeries. Simultaneously.

And get this: They don’t even tell you it’s happening, or ask you whether you’re O.K. with it. They just go ahead and do both surgeries at the same time without the two patients ever knowing.

This is really happening. Every day. In 2019. At legit, reputable hospitals.

Without anyone really noticing and almost no media attention.

The only reason I found out that I was involved in one of these concurrent surgeries was because I initiated a lawsuit and, in the course of litigation that lasted six years, was able to gain access to hospital records that revealed what went down. Otherwise, I would’ve never known what had actually happened to me.

But through the discovery process we eventually found out that the night before my scheduled surgery a patient had been admitted to the hospital after being paralyzed in an accident, and the hospital scheduled a surgery for this person, with my surgeon, at a time that overlapped with my procedure.

So now the doctor overseeing my spinal surgery is also doing that other surgery, too. While he was in the operating room with me, the other patient was in another room under anesthesia waiting to be operated on.

Our filings in the lawsuit, which recently settled out of court for $5.1 million, argued that because this doctor was leading two procedures at once, he was not able to provide either patient with the appropriate level of care. And, in my opinion, the reason why that bony spike was left in my body was because the doctor had rushed my surgery and wasn’t as careful as he should have been. He had to get over to that other patient, and, as a result, he screwed up my procedure.

That sort of thing, and much, much worse, is happening at hospitals all over the country because of how some surgeries are now being scheduled to overlap.

And it’s simply not right.

It wasn’t until I filed a malpractice lawsuit, and did some digging, that I found out what exactly had gone so very wrong.

The main reason why I wanted to tell my story — the full story, warts and all — is because I’m hoping to use my platform to start a movement in this country against concurrent surgeries. I don’t want more people to suffer as a result of a practice that is so obviously inappropriate and dangerous.

I’m convinced that part of the reason why these concurrent surgeries are happening is because hardly anyone knows this stuff is going on.

And, well … it’s time for that to change.

My hope is that I can be a big part of driving that change. And it all starts with me writing this article — with me telling my entire story, and coming clean about my struggles over the past decade or so.

I’d be lying if I said writing this thing has been easy. It hasn’t. It was painful and agonizing and, at times, completely embarrassing. I’m ashamed of many things I did in the past. So of course being open and honest about it was … rough. But if telling my story, and putting everything out there for the world to see, helps create momentum for a movement to stop concurrent surgeries, then doing this article will be one of the greatest achievements of my life.

I’m proud to say that I’m now seven years and three months sober. I’m living out in California with the woman who played the biggest part in me getting and staying clean, my second wife, Eleni. I’m taking things day by day, doing my best. And from here on out, I just want to try to help as many people as I can by fighting to end this insane practice of concurrent surgeries.

So, if after reading my story you find yourself as bothered by the existence of concurrent surgeries as I am, I urge you to take some action. You can start by sharing the importance of “informed consent” for anyone who may need a surgery. A direct discussion with the surgeon about this type of practice, and insisting that a concurrent surgery is not part of the plan, is something everyone can do at the individual level. In addition, there are currently efforts in Massachusetts to sign a bill into law prohibiting concurrent surgeries. While these efforts are still in the early stages, it’s a start. And ideally Massachusetts can provide an example for those in other states to follow. Maybe you can help lead that charge.

And know that I’ll be right there with you, because I have no desire to stay quiet about this stuff. You can definitely count on hearing a lot more from me about it in the future.

Now that my baseball playing days are over, I feel like I’ve found another passion that I can throw myself into and hopefully make a real difference.

And I’m ready for this battle.