Big, Small Town: My Introduction to Dallas

Last summer, a couple of days after I signed with the Mavericks, I packed up my things and got on a one-way flight to Dallas. I had a new job and I was moving to a new city — a place I didn’t know very well. I’d heard Dallas described as a “big, small town” before, even before I moved. As a kid from an actual small town in Iowa, I was never sure what to make of the description.

When my plane touched down, my mind was going in a million different directions. I remember being overwhelmed by all the things — mostly trivial little things — that you tend to get preoccupied with when you’re making a major life change.

I landed to find a city in mourning.

You could feel that something was going on. The TVs in the airport were tuned to CNN and people were huddled around, watching mostly in silence.

Five killed.

Dallas on lockdown.

One of the worst attacks on police officers in the nation’s history.

It was the middle of July. A really humid day, the kind of heat that wraps around you right when you walk outside. In a car from the airport, I remember seeing all the DALLAS STRONG signs on storefronts and on front lawns. My driver told me that the city felt different, like everything was on hold until the memorial service.

I’ll be honest: For a moment, I felt like turning around. Not because I didn’t want to be there, but because I felt like an outsider, a total newcomer who was barging in on a community’s most sensitive hour.

The memorial service was the next day. I wanted to pay my respects, but I didn’t want to get in the way. I talked about it with a friend who lives in Dallas — and he didn’t wait more than a second to respond. He encouraged me to go.

Everyone in Dallas, he said, was either going to attend the memorial or stay home and watch it live on TV.

“In this town, we’re family,” he said.

Political leaders from across the country descended on Dallas for the memorial. Former president George W. Bush was there. So was President Obama, who gave an incredible speech.

“In the aftermath of the shooting,” he said, “we’ve seen Mayor Rawlings and Chief Brown, a white man and a black man with different backgrounds, working not just to restore order and support a shaken city, a shaken department, but working together to unify a city with strength and grace and wisdom.”

It was the kind of soaring speech that you hope for from a president in such times. One line from his speech has stuck with me. “We are not as divided as we seem.”

Ever since I was a kid — growing up in a small town in Iowa, going to Chapel Hill for college and then to the Bay Area — I’ve been interested in how communities come together to solve their differences. And I’ve always been drawn to politics and social change. My parents instilled in me not only the importance of having a work ethic on the basketball court, but also the importance of having a commitment to your community.

David Brown, the Dallas police chief, delivered some of the memorial’s most memorable remarks. I remember his black-framed glasses and his poise. I remember how he spoke slowly, confidently. It had only been a few days since his department — his community — had lost five fellow police officers. Chief Brown’s concluding remarks still stick with me:

“We’re your brothers and your sisters,” he said. “When you need us, you call. Because we will not only be loving you today, we’ll be loving you always, always, until the end of time. We’ll be loving you until you are me and I am you.”

I walked away from that experience saddened by the tragedy, but impressed by the warmth and solidarity of everyone I met. Since then I’ve been thinking a lot about what my role in this new city might look like.

A few months ago, I saw Chief Brown for the first time since the memorial service. This time, it was at a dinner table. (Chief Brown had since retired from the police force.)

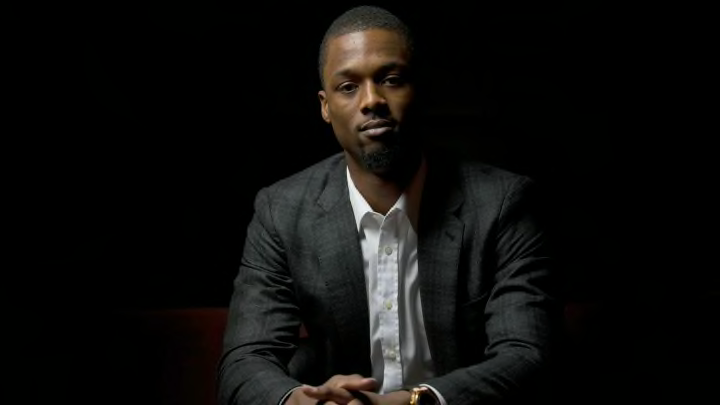

I had organized a dinner party at the home of a friend for a group of Dallas’s leaders. My hope was to have an open conversation with people who know the city — and to hear from them firsthand about ways I could get involved in the community.

Let me back up for a second to explain. When I moved to Dallas, I had two big goals. The first, of course, had to do with basketball. I came here to work hard and earn the respect of the fans. The second goal was more personal. I wanted to put down roots in Dallas. That was one of the upsides of signing a four-year deal.

Like I said, I’ve always been drawn to political and social conversations. Even though basketball takes up most of my time, I try to pursue intellectual interests whenever I can. Last year, when I was still playing for Golden State, I reached out to Representative Eric Swalwell, the congressman who represents the district in California that includes Oakland. On a road trip to play the Washington Wizards last spring, I was able to set up a meeting with him. After a tour of the Capitol, we talked about both “serious” subjects — like affirmative action and health care — and more lighthearted stuff. I asked about all the ins and outs of being a legislator … and he wanted to know things like, “What’s the Warriors locker room like?”

On the day of that dinner a couple of months ago, I still wasn’t quite sure who was actually going to show up.

As the food was being served, I found myself sitting two seats down from Emmitt Smith. Directly across from me was Chief Brown. Next to him was Mike Rawlings, the mayor of Dallas; then Ron Kirk, the first black mayor of the city, who served in the mid-to-late ’90s; then David Huntley, the Chief Compliance Officer at AT&T, one of the city’s biggest employers; then a local high school football coach; then me (the new guy); then Michael Finley, who’s now on Mavericks staff; then the founder of one of Dallas’s most successful entrepreneurial investment firms. Rounding out the table was a power couple: Taj Clayton, a nationally prominent lawyer, and Tonika Clayton, a managing partner at an educational venture capital firm in Dallas.

The conversation took off without much prompting — Chief Brown’s candor helped break the ice. He talked about the perceptions of Dallas police from two perspectives: as a kid who grew up in Oak Cliff, right outside of Dallas, and later as a police officer who, in his early 20s, patrolled some of the same streets he’d grown up on. He talked about the gap in trust between communities and the police. To Chief Brown, it was personal. Over the course of his career he has seen how community policing can bridge the trust gap — and also how racial profiling and police brutality can damage that trust.

Chief Brown also talked about how Dallas had shaped his childhood. When he was growing up, his mom worked at Texas Instruments, another big Dallas employer, and through that he got a scholarship to attend a prestigious grade school. The opportunity for an education was turning point for him.

Throughout the dinner, I only talked a little bit. Mostly, I listened.

Soon we moved on to new subjects — public education, health care, poverty and more. The dinner and the conversation went on for more than 90 minutes. I can truly say that I haven’t been involved in a discussion as honest and personal in a long time. There was no shortage of disagreement about the fundamental social and political issues facing Dallas. But one thing was crystal clear: Everyone there cared deeply about this city. The common thread was how to solve the seemingly intractable problems facing the city. How does Dallas begin to transcend its racial and economic divisions? How can the community create better opportunities for young people who are struggling? Which problems are best suited for government intervention and which are best suited for the private sector?

We were all sitting at a table together on a Monday night in January, acknowledging that the problems were big … and that doing nothing was unacceptable.

At one point, in the middle of a discussion about police profiling, Emmitt Smith chimed in.

“One of my first weeks in Dallas, I got in a car accident,” he began.

All eyes turned to him.

Now, I’ll try to retell his story as best I can, but just keep in mind that Emmitt told it way, way better in real life. The guy can straight-up hold a room.

It was 1990. He was a rookie on the Cowboys, still a newcomer in Dallas. One night he was driving through North Dallas and he pulled up to a red light next to a car full of teenagers. He had the stereo blasting, and the teenagers were bobbing their heads, admiring his car.

“300 SL coupé. Burgundy.”

He started to move through the intersection after the light changed, and then, out of nowhere, another car ran the light and collided with him. No one was injured, and both Emmitt and the other driver pulled over to the side of the road to assess the damage. A police cruiser showed up a few minutes later. The other driver was claiming Emmitt had run the red light.

Then the two officers came up to Emmitt’s car. As he told it, the first two things the officers asked him were: “What are you doing in this neighborhood?” and, “Whose car is this?”

“What’s that got to do with the price of tea in China?” Emmitt said, “I just got hit!”

Now, this was before Emmitt was Emmitt. He wasn’t a recognizable person in Dallas yet. This was the early ’90s — before the Super Bowl rings.

The mood of the officers felt hostile, Emmitt said. At the time he was wondering why the officers weren’t spending more of their energy talking to the person who had caused the accident. It seemed clear to him, based on the damage to each car, who was at fault.

And right then, the teenagers — the same ones who had been admiring his car earlier — pulled up.

“We saw it all!” They said, describing the accident the same way Emmitt had. “This guy had the green light!”

The officers ran his info and came back to his car. The vibe changed suddenly.

“You’re Emmitt Smith!” one officer said. “Why didn’t you say something?!”

The officers arranged for his car to be towed and even gave him a ride to a garage.

“So that was one of my first experiences in Dallas,” Emmitt concluded.

Emmitt’s story prompted everybody at the table to talk about police-community relations in Dallas, and how to address issues like profiling. It was pretty amazing hearing a debate on those subjects between an NFL legend, two mayors and a police chief.

As inspiring as the dinner was, I came away from it committed to making sure that it’s not the last time the group meets. Going forward, I want to interview different people in Dallas — across various industries and from various backgrounds — to learn more about the many faces of this community. I’ll publish some of those interviews here on The Players’ Tribune.

The dinner was a start. I’m hopeful that it can lead to real action, not just talk. I want to make sure what I do — what we do together — goes beyond conversation.

As the dinner was coming to an end, I thanked everyone, and before getting up, I asked for any parting advice.

Ron Kirk, the former Dallas mayor, didn’t mince words. Drawing on his experience as mayor, he talked about his experience with charitable foundations in his tenure — about how they pop up every year and then are gone the next. He spoke about the celebrities and athletes who ask how they can help, but then fail to follow through.

“Whatever you do,” he said, “Stick with it. Be present.”

I nodded in agreement.

I could see he wasn’t expecting an answer right away.