I'm Out

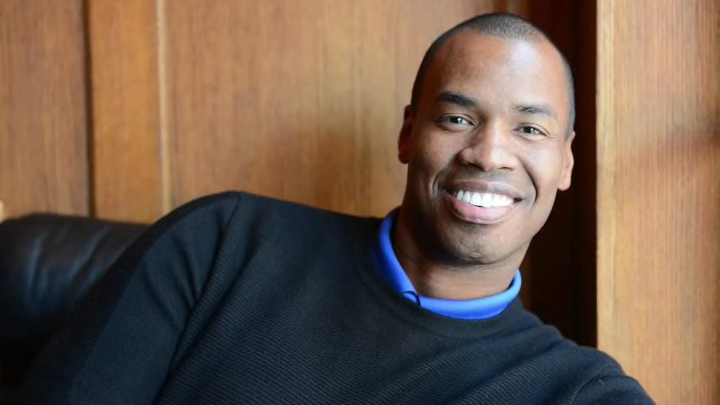

Today, I am retiring from the NBA after 13 seasons. Most people reading this probably don’t know me from SportsCenter. Most people know me as “the gay basketball player.” I have been an openly gay man for approximately three percent of my life. I have been a professional basketball player for almost half of it.

In order to understand why I am so lucky to be sitting here today as a person who is finally comfortable in his own skin, you need to understand how basketball saved me. I needed to live the past few years as an openly gay basketball player in order to be at peace retiring today. Why? It starts on a bus and ends on a plane.

*

“Hey Jason … Jason! How come we never see you with any women? Are you gay?”

The team bus was uncomfortably silent. Everybody from the front of the bus to the back heard the question. It wasn’t the first time something like this had happened. In sports, guys bust each other’s balls all the time. I had been asked that question a few different times by teammates in my previous years in the league, but this time was different. Whenever guys would go out on the town on road trips, I always had a built-in excuse—a trip to a local casino or a visit to a family friend or a college buddy in that city who I had to go see. Sometimes those friends were real. Sometimes I made them up and would sit alone in the hotel watching TV while the guys went out to enjoy the nightlife.

It was a lonely experience, even when I was around other people. It was always mentally draining, because I always had to be on, 24/7. Whenever I went out to dinner with teammates, I became especially skilled at steering any conversation away from the personal and back to the realm of sports or entertainment. After a while, guys just know you as the vet who loves to talk basketball. When you go to a new team, you have to create that character all over again.

“I think you’re gay, dude.”

Every other time, I could find a way to laugh it off. This time was different. I was 30 and unmarried. No kids. No crazy road stories. For years, I had dated women—never men, even secretly—but now I was starting to be more honest with myself about my sexuality. I felt like maybe the guards I had put up were starting to wear down. This time, the question stung like it never had before. There’s a very particular feeling in the pit of your stomach when the question comes up. I call it the blush. You feel angry, yet also embarrassed.

It felt like everybody on that bus was looking at me and could see right through me. Part of me was tired of running. Part of me wanted to scream out the truth and just get it over with, but I couldn’t. In a split second, that familiar survival instinct kicked in and I thought, Okay, I have to prove to these guys that I’m straight.

As ridiculous as it sounds, I asked myself, What would a straight guy do in this situation? So I pulled the fake-heated mean-mug face. Like, no way am I gay. Me? Are you serious? I started talking about a girl who had conveniently come to visit me that week. Of course, this girl was just a friend, but the guys didn’t know that. So I just kept talking, hoping I sounded believable. I felt like I was sinking in quicksand. It was so silent you could hear a pin drop.

Finally, somebody yelled out from the back of the bus, “Hey, what are you talking about? I saw him out with that girl the other night. Come on, man. You crazy. He’s straight.”

My teammate vouched for me.

Maybe he really saw me out with her, but I think he was just throwing me a lifeline. Whatever the case, the awkward silence broke. Guys started talking again. I slid back down into my seat. I had avoided the question one more time, but I knew I couldn’t keep up the act. It was exhausting.

On one hand, I felt pressure to be “The Perfect Son” for my family, which had always been incredibly loving and supportive of me. I wanted to keep up the hope for my parents that someday, when basketball was over, they would have the big traditional wedding and the grandkids from me and my wife. I was afraid of being rejected by my family and friends, much more so than being run out of the NBA.

On the other hand, by trying to keep everyone around me happy, I was becoming increasingly lonely. No matter your religion or what your political views are, I think there’s one thing we can all agree on. Most human beings are not meant to be alone. I know I’m not.

Later on that year, we faced the Orlando Magic in the playoffs, and I was given the unenviable task of guarding Dwight Howard. By that point, my battles in the post with Shaquille O’Neal over the years were starting to catch up with me. I used to play this game with Cliff Robinson where we’d come up with names for the moves Shaq used to punish you. “There’s the ol’ meat cleaver! Aw no, there’s the spine tingler!”

Shaq is responsible for a whole bunch of seven-foot-tall middle-aged men hobbling around America right now.

So my back was getting creaky, and Dwight was a 25-year-old beast. My job was the same as it had been my entire career: Make his life as miserable as possible. Bump him. Foul him. Stick a hand in his face and pull out every single wiley vet move under the sun to keep him from dominating the game.

Of course, he had his moments. He’s Dwight. He averaged 27 points a game. I averaged 1.8. But, when it mattered most, we kept him from hurting us. We won the series in six. Coach Van Gundy said it was the best defense he had seen on Dwight all year. But, I was essentially invisible. I barely talked to a single reporter during the whole series.

What a crappy, thankless job, right? To me, it was perfect. When I came into the NBA from Stanford, I had already decided what type of player I would be. I wanted to be the best player and teammate I could be, but not attract too much attention or make too much noise. I didn’t want people to start asking questions about my personal life.

I realize that might sound like a very convenient excuse for spending my career as a defensive grunt, but it’s just another example of the constant strategizing you do when you’re closeted. Every single moment, you’re paranoid that your words or actions could undo the whole charade.

With Twitter and Facebook, these mental gymnastics become all the more complicated. During that 2011 offseason, as the debate around “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” and DOMA was heating up on social media, I had to pull out every last ounce of self-control to keep myself from retweeting something in support of marriage equality. Watching people I admired come out in support of the issues that were so dear to my heart was helping me get closer and closer to revealing the truth. But I was still scared.

When the 2011 NBA lockout kept me away from my normal routine, I had way too much time on my hands to be by myself—my authentic self—and read about the fight for equal rights in the LGBTQ community. I would keep track of what was going on via OUTsports.com every day, making sure to clear my browser history and cover my tracks. With basketball distractions taken away, I finally had to confront the reality of my existence as a human being on this planet. What did I want my legacy to be? What did I want out of life?

I had days and days by myself during the lockout and the only one I was able to have a full unguarded conversation with was Shadow, my German Shepherd. Granted, it was a one-way conversation.

I’d had enough. I wanted to be free. A few months later, after 33 years of not telling a single soul, I came out of the closet. First to a friend in Los Angeles, then to my aunt Teri. She said she had always known, and she was fully supportive. With that initial burden lifted, I told my family and close friends next. Unlike Teri, my twin brother Jarron was stunned. To be honest, I was pretty surprised that I was able to fool him for three decades. This is the guy I spent more hours talking to than any other person in my life. For the first time, he saw the real me. He had absolutely no idea.

Within a few hours, after the surprise wore off, everything with Jarron was back to normal and today, we’re closer than ever. He is one of the best men I know.

Of course, life is not a Disney movie. Life is messy. There were some people in my family who made gay jokes and used inappropriate language while I was growing up. Coming out to some people was more challenging than others, but in the end, I was amazed by how much my sexuality didn’t matter.

That’s the secret that every single closeted person reading this—athlete or otherwise—should know. In the end, the people who genuinely love you will always love you and support you, no matter what. It’s the secret I wish I had known for 33 years.

When I decided to come out publicly with my letter in Sports Illustrated in April 2013, I was fully prepared to never play in the NBA again. Being an older free agent, I was dreading the “D” word. He’s a Distraction. Why bother? But I was also bracing myself to hear a lot worse, whether it was from opposing fans or from players. I had been in sports locker rooms since my high school days in the mid-’90s. I knew how guys talked. Athletes can be very … colorful with their language.

I had no idea what to expect.

*

“… Wait, who is this?”

I was coming out of a boot-camp workout in LA a few days after the Sports Illustrated article published when I got a call from a number I didn’t recognize. It was a 305 area code. I thought, who the hell is calling me from Miami?

“Hey, this is Tim Hardaway,” the voice said.

Tim was an old-school athlete who came up in the ’90s when homophobia was still commonplace, expected and accepted. When retired NBA player John Amaechi came out in 2007, Tim made some negative and unsupportive comments that made headlines. To Tim’s credit, he later apologized for his comments and has worked with several groups to educate himself on LGBTQ issues. Tim has since become an activist and straight ally for the LGBTQ community.

Still, when he called me, I was stunned.

He said, “I just want to tell you that I’m really proud of you, man. You have my support.”

Tim may never know just how much that meant to me. That was major. In that moment, I knew that it was possible for a person to change in their heart and mind. If Tim supported me, I knew there would be others that did as well.

Now that the burden of hiding was finally off of my shoulders, I was confident that if an NBA team came calling, I was capable of doing my job, maybe better than ever. I spent the rest of the summer torturing myself with workouts, running up and down the trails of Los Angeles in order to get in the best possible shape of my career. I lifted weights that would make a football player proud. You could see the veins in my biceps for the first time in over a decade.

I knew the easiest excuse for any NBA team to explain passing on me would be that I was out of shape. At 34, it’s not hard to get flabby. Despite interest from a couple of teams, the entire summer and fall came and went without an offer.

Then, in January, I was invited to Washington D.C. by the White House for the State of the Union address. I had the pleasure to join the First Lady in her viewing box during the speech. Afterward, there’s something called the receiving line, where all the invited guests of the First Lady wait in line to greet the President and take a picture with him. Usually this process is rather quick as you shake hands, say a few words, and move along for the next person. At least that’s how it works with normal people. Unfortunately, as my friends love to point out to me, I am the Black Larry David.

Awkwardness follows me.

So President Obama gets to me and without missing a beat he says, “Hey Jason, nice to see you. Have you been staying in shape?”

“Yes, Mr. President. I just ran five miles yesterday,” I said. “I’m ready.”

“That’s good,” he said, “Because you know, after the All-Star break is when all the free agents get picked up, so stay in shape.”

At this point, I should have smiled and said, “Thank you, Mr. President, I will.”

I did not do that.

“Oh yeah, Mr. President,” I said. “I’d show you my six pack, but I don’t think the Secret Service or your wife would want me to take my shirt off right now.”

I have rarely seen the President at a loss for words. He is always smooth. This time, it took him a second.

“Uh, well yeah, that’s a good idea,” he said. “You should probably keep your shirt on.”

He grinned, shook my hand and turned to the next person.

President Obama turned out to be absolutely right.

After the trade deadline in late February, I went to my brother’s house with my friends and family for board game night. We played Celebrity, a modified version of charades. It was so fitting because it was one of those nights that made me realize how lucky I was to finally be free and happy in front of the people I love.

The next morning, at 8 a.m., my phone blew up with text messages and voicemails. One of the first messages was from my old teammate, Jason Kidd, who was then the head coach of the Brooklyn Nets. Most of the money I made in the NBA I probably owe to J-Kidd. He was one of the smartest players I ever played with—one of those point guards who could make a big man look so much better than he really is, just by feeding him easy buckets.

For seven years, J-Kidd and I played together in New Jersey. Now, he and the entire organization were welcoming me back to the Nets on a 10-day contract.

After that, everything happened really fast. I’ve often been asked if I was nervous to face the team for the first time. Honestly, I barely had time to think about it. I was more worried about how I was supposed to pack for a road trip. There’s only so much you can fit in a few travel bags, and when you’re a seven-footer, you can’t just roll up to the mall and buy normal-size jeans. I remember packing thinking that my wardrobe rotation was going to be very limited if I end up staying with the team for the rest of the year.

Everybody wanted to know what it’s like to play in a game as an openly gay man in the NBA. From the moment I stepped onto the court to the moment the final buzzer sounded—it was the same as my previous 12 years.

I was locked in. Nothing was different. I did what I always do. Being gay certainly didn’t affect how I played. I tipped rebounds to teammates, tried to de-cleat opponents with my screens, and I did my best to make life miserable for the opposing big. When the ball tipped off, I realized something that I wish I could instill in every single coach, GM, and player reading this.

IT’S STILL JUST BASKETBALL.

The ironic thing about the dreaded D word is that I had never felt more comfortable playing basketball than I was as an openly gay man. You know what a real distraction is? Maintaining a lie 24 hours a day, seven days a week, for most of your career, for most of your life. The energy involved in hiding the stress, shame, and fear of being gay is a full-time job. With all that removed, I was like a new person.

In the locker room after the first few games, there were a lot more cameras in front of me than usual. (A big thank you to Gary Sussman and Aaron Harris in the Nets media department for acting like my guard dogs, yapping at any media members who stepped over the line.) After a couple weeks, the media coverage shifted off of me because there are only so many ways you can write a story about having a gay teammate. It went back to being about the team and how we were making a push for the playoffs.

In my first 10 games with the team, we won eight and lost two. So much for that distraction theory.

As all good teams do, we were able to come together and have fun, and poke fun at each other as usual. One day, Andray Blatche got fed up with my wardrobe and called me out.

“Bro, I swear if I see you wearing those black jeans one more time,” he laughed. “You gotta switch it up, man.”

I responded to him saying, “Is that a t-shirt? Or a blouse you’re wearing? Either way, Prince & The Revolution just called and they want their clothes back!”

Yep, it’s still just basketball. Still just two teammates cracking jokes on each other.

On the team plane after the third game, I was watching a movie when a future Hall of Famer tapped me on the arm.

I had known Kevin Garnett since high school. When I was 15, my brother and I played against him at a tournament in Las Vegas. As a young man I was good; but KG was on another level. He had 19 blocks against us, and he was talking trash even back then. It was one of those monumental moments in life when I was like, I needed that. I’m not as good as I thought I was.

That game is one of the reasons I ended up making it to the NBA. Because there were two ways I could’ve gone. I could’ve tucked my tail between my legs and taken up golf. Or I could’ve gone back to the gym with a vengeance.

I got back into the gym. Now, here we were, 20 years later, two old vets sitting across from one another on an NBA charter flight.

“Hey JC,” Kevin said. “I’m really glad you’re back playing, man. That you’re back playing in the league and you’re on our team. You know, this is going to be big for society.”

It is extremely meaningful to me that he would express those words of support. At that point, my head was spinning just trying to learn the plays. I wasn’t thinking about the historical significance of a gay player in the league. I just wanted to be one of the guys again. For Kevin to go out of his way to say he appreciated me as a teammate meant a lot to me as a basketball player.

There are so many people I have to thank for helping me on my journey. My family, friends, and fans empower me each and every day. My teammates, coaches, and the Brooklyn Nets organization gave me an opportunity. The entire NBA family, where the leadership of David Stern and Adam Silver created an environment that made me feel safe to step forward. My agent, Arn Tellem, who is like the cool uncle everyone wishes they had. All the fans in New York who would see me walking on the street and say, “Hey Collins, good luck tonight!” or “We are proud of you!” To all the people who came out before me and helped clear the path for others to follow. And the many countless individuals who have fought and sacrificed for human and civil rights, period. Thank you.

Many people have asked, “What’s next?” I’ll continue to encourage others to live an authentic life. My hope is that everyone achieves that day when you step forward and reveal your truth on your own terms. Your life will be exponentially better when you celebrate all that makes you unique. Additionally, I hope to inspire others to create a world of acceptance and inclusion; not only by their words, but by their actions.

What would you have done if you were on that team bus with me?

It’s easy to say you would’ve done what my teammate did, or something else to alleviate the situation. But when you’re in that moment, it’s a lot easier to pretend that you didn’t hear what was happening, or to throw on your headphones, or perhaps easier still—to laugh along with others.

This scenario plays out every single day on buses, school cafeterias, and office buildings across the world. Maybe 10 closeted athletes will come out and be free over the next year. Or maybe not. People ask me all the time, “Don’t you think we need more athletes to come out?”

Yes, of course I do; that would be great. However, if we really want to make the world a better place, we also need more people like the teammate who saw me drowning and threw me a lifeline. You can be that person who speaks up.

Thanks for all the love.