The Scar

As a professional athlete, I rely on my body to listen to my mind like a Formula 1 driver expects his car to respond to his maneuvers. I take great pride in my fitness, strength and athletic ability. I know that I have a God-given gift.

One morning, five years ago, that special gift was taken away.

Following a routine NBA physical with the Boston Celtics, I was diagnosed with a dangerous enlargement of the valve to my aorta, the main blood vessel in the body. Most people only find out about this condition after the aorta ruptures, which is usually fatal. The Celtics doctor found the top aortic valve surgeon in America, Dr. Lars Svensson, who performed open-heart surgery on me in January 2012.

When I woke up after surgery, Dr. Svensson told me, “Look at yourself in the mirror, when you get a chance. You are going to see a different person” and that I needed to get used to that. For the first few days, I wouldn’t get up and look. I didn’t want to take off my gown and look at my chest. I just stayed in bed. By about the fourth or fifth day, I finally limped over to the bathroom, took off my gown and stood in front of the mirror.

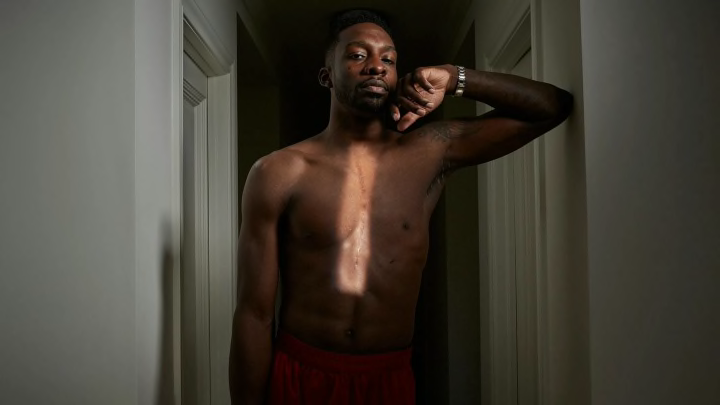

I was shirtless, just like I’d been a thousand other times during pickup games or practices. But, this time, I didn’t recognize the body I was looking at.

Instead of the smooth, muscled chest I was used to seeing, there was a long, jagged, pink line from the base of my neck to the top of my abdomen. It was a scar, running nine inches across my chest. That wasn’t all. Right above my abdomen, I saw three huge, sewn up holes from where tubes pumped fluids in and out during the surgery. (Years later those marks are still there. They look like bullet wounds.) And there were divots from the 16 rods that held open my rib cage — where Dr. Svensson and his team at the Cleveland Clinic opened my chest — that ran along the length of the scar. At the bottom of the scar, right above my abs, there was a section of skin that resembled the rectangular, springy end of a diving board, and you could see the stitches poking through the bottom of my chest.

In one day, everything I knew about my body had changed. And all the confidence I had felt about maintaining this body had been completely drained.

Standing in front of the mirror, I started crying. It was hitting me — this is forever.

About a week into recovery, I headed to a physical rehab in Waltham, MA that the Celtics had set me up with. A lot of people there were recovering from various kinds of heart operations themselves — but I was the only person there under 60 years old. I remember this one older man and one older woman who were always on the treadmills next to me. They would be walking for 10-20 minutes at a time, no problem. At that time, in the first weeks after my operation, I could walk for about five minutes on the treadmill, but then I’d be exhausted. My doctor promised me that each day I would get a little bit better, but it was easy to get depressed about my progress. Sixty-year olds were lapping me on the treadmill.

But every day, I would see the same man and the same woman next to me on the treadmill. And something specific about that man and woman’s attitude completely changed my perspective.

They never stopped smiling. Like, 24/7. Walking and smiling. That inspired me. You can do this, I thought. Keep pushing, Jeff.

My attitude got a lot better during that period. But I still couldn’t really process that fresh, raw scar — it was a constant reminder of how real this all was. I just wanted the scar to go away. I was dousing that thing in special scar cream, cocoa butter, whatever I could find that promised to accelerate the healing. You can ask my dad — I was obsessed with any product that could somehow make the scar go away. I didn’t want to face it at all. But after weeks of doing all that maintenance with very little impact on its appearance, I realized the scar wasn’t going anywhere. I didn’t have much of a choice: I decided to at least try to own the scar. And the best way to do that, in my mind, was to make it part of my routine. I’m gonna show this thing off, I thought. I’m gonna take my shirt off anytime I’m lifting or working out. That way, I’d be forcing myself to adapt.

After a month or so of rehab, I rejoined the Celtics. I wasn’t jumping into full practices yet, but I was working a lot with the strength coach, Bryan Doo. And every time I worked out, I’d make it a point to do it shirtless. Immediately, some guys on the teams were… well … surprised by my decision to pop that shirt off. Kevin Garnett caught me one time — “Dude, put your shirt on!” Same with Paul Pierce, Courtney Lee, even Bryan. I don’t care what they think, I’m keeping the damn shirt off, I thought. They were pretty shocked at first, because at that point the scar was still pretty nasty. But eventually I think they got what I was doing — they saw that I needed to motivate myself, and to remind myself what I was coming back from. After a while, everyone was normal about it. It even got to the point where my teammates thought I was being too cocky with it. I’m showing this thing off, baby.

Before, I hated my scar.

Now I needed it.

I needed to see the scar to remind myself of what I’d been through. And every reaction I got about it only served as another reminder. I couldn’t help but smile. If the scar was still there, it meant I was still alive.

Last year, I got signed to a new team, the Orlando Magic. Before a game one time, a new teammate was asking me about my surgery and what the recovery was like. Elfrid Payton overheard us and came over to join the conversation.

“Jeff,” Elfrid said. “You had HEART surgery?!”

I was like, Yeah man, five years ago! He was shocked. But then he had a whole bunch of questions about it, and I found myself genuinely enjoying telling Elfrid the whole story.

It’s been more than five years since January 2012 when I woke up in the hospital after my operation. There’s not a day that goes by where I don’t feel the scar on my body. It’s healed a lot, but it’s still the same size as it always was. When I run my hands along it, it still feels like the entirety of my chest. The texture of the scar, and its appearance — those things will never change much. It’s always going to be a part of me.

I might not pop my shirt off as much anymore. But everything changed when I decided to own that scar, not hide from it. It’s really amazing — the same thing that terrified me at first became the symbol for everything I’ve been through.

Now, when I look in the mirror, I see Iron Man.

Jeff Green has donated an autographed pair of Air Jordan XXXI shoes commemorating his open heart surgery to the Cleveland Clinic Foundation (CCF). The shoes are one of two pairs that were exclusively created for Jeff by Jordan Brand. To enter a raffle drawing to win these special shoes, with proceeds benefiting CCF, please visit Jeff's campaign or click on the donate button below.