Wrecking Ball

I caught the bug pretty early.

It started out as nothing unusual. It was, “Mark plays all kinds of sports.” And that was true. Soccer, basketball, baseball, hockey — really, I played everything growing up in Kamloops, B.C., along with my three brothers.

I was just that kid who liked sports. I was never bigger or stronger than the guys I was playing with. In fact, I was usually one of the smaller guys. But I just — I don’t know. Maybe I got the sweatiest. I was addicted. I had the fever. Whatever you want to call it. I liked sports.

And I always wanted to be playing sports, all of the time. I was always warmed up and ready to play.

Throw the football after school? You bet.

Baseball Saturday in the park? I’m there.

Is that a Frisbee? I’d instantly make the universal “toss me the Frisbee” hand signal.

But when people asked what I wanted to be when I grew up, I usually told them a police officer or a fireman. And, actually, I probably would’ve gone that route if hockey didn’t work out. But, really, I already knew, even back then — even if I wasn’t talking about it.

I wanted to be a professional athlete.

I didn’t think about being the best player in the league. I certainly couldn’t even imagine making it into the Hall of Fame at any point — but I wanted a future in sports. It’s all I wanted.

When you’re a kid, even a teenager, and you tell any adult that you want to play in the pros, they’ll most likely just roll their eyes at you.

“I bet you’ll score a hundred home runs, kid!” And maybe they’d ruffle a hand through your hair before walking away.

So I didn’t go out of my way to tell people I wanted to be an athlete. But as I got older, the list of sports I loved shortened.

Mark plays soccer, baseball, and hockey.

Mark plays baseball and hockey.

Mark plays hockey.

Mark. Hockey.

Mark Hockey. Mark Recchi. See, it all makes perfect sense when you think about it.

Hockey took over my brain. When I wasn’t playing hockey or watching hockey, I was thinking about the next time I’d be playing hockey or watching hockey.

There was no trick to how I stayed in the game for so long. I didn’t have any superstition or secret breakfast that kept me in the game. Didn’t have a real pregame ritual like so many great players do. I’m not really even superstitious at all, about anything.

Like I said, I always liked to play sports. I was also pretty lucky.

And I just really, really love hockey.

Gilbert Perreault and Bryan Trottier were probably my favorite players growing up. When I first got to Pittsburgh I even had a locker next to Trots. I wouldn’t tell him he was my favorite player until like 10 years later.

“These are the big leagues,” I told myself. “No more favorite players.”

I didn’t want to look like some starry-eyed kid just happy to be on the team. But that’s what I was. For a couple of years I did my best to look the part.

I certainly wasn’t any kind of phenom in high school or anything like that. In juniors, I was always on good teams in Kamloops. We were always competing for some kind of district or national championship.

But a lot of scouting reports had me as an undersized, potentially risky forward. My game wasn’t flashy. I played inside the dots, in front of the net. I was decent at hitting guys.

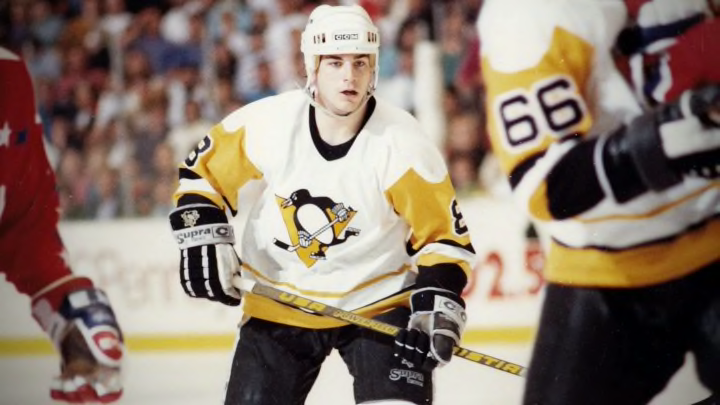

So the Penguins drafted me in the fourth round of the ’88–89 draft. After spending a year in the IHL, I was on the Penguins roster for good.

I didn’t even have time to take a look around and realize who I was playing with. Looking back, it’s hard to even believe. Trottier, Jagr, Francis, Lemieux. It was like being put onto an All-Star team before I had even played a single NHL game. It’s hard to concentrate when you’re around guys like that and you’re barely 20 years old.

Again, I told myself to just keep doing the same things that brought me to the NHL. I worked very hard every day to try and prove that I wasn’t taking the opportunity for granted.

Actually, I can’t say that it ever felt like “work.” I was doing it because it was hockey.

I scored 113 points in the regular season. We won a Stanley Cup. I was 23 years old and had achieved the ultimate goal of any professional athlete.

“This is it,” I thought. “How could it ever get better than this?”

That summer was more surreal than anything I had ever experienced. I went into the following season on top of the world. More than anything, I was just excited for the season to start so I could be playing again.

Then, all of a sudden, I was somewhere else. After winning the cup in 1991, I was traded from the Stanley Cup champion Penguins to the Philadelphia Flyers, a team that was known to be in rebuilding mode. Right in the middle of the season.

Pittsburgh won the cup again in 1992. Philly won 32 games the whole year.

I wasn’t angry or bitter when I was traded to Philly. Of course it’s sad seeing your friends win the big one without you, but I was young and healthy and just happy to be playing, so I knew that I’d get another chance.

… And then a year went by.

And another.

I wouldn’t even sniff the playoffs for five years after leaving Pittsburgh. Not until I was traded from Philly to Montreal. And then I went from Montreal back to Philly. Then from Philly, back to Pittsburgh.

Finally, 15 years later, in 2006, I’d win another cup. In Carolina.

15 years is a long career by any standard, in any sport. I went 15 years between Stanley Cups.

Didn’t feel like 15 years, to be honest with you.

Time flies when you’re having fun.

I never even got worn down after year 10 or 11, when I hadn’t won in so long. Every year, when a new season started, I was just thrilled to be on the ice again. A new season was a reset button. It didn’t matter where I was, or what the team’s record was the year before — another year meant another chance to go all the way. And another season of playing hockey.

How could it get any better than that?

I was playing in Boston when we lost to the Flyers in the 2010 Eastern semifinals, and before that season started I had already told the team that it would be my last year. I was comfortable with that decision at the time. Going into the playoffs, we were on top of our division, and everyone in the locker room was confident about our game. We felt like we had a real opportunity to win it all.

But we lost. We were up 3-0 in the first period of game 7. Then all of a sudden we were tied. Then, before we could blink, our season was over. Just like that.

I was crushed. My heart had been ripped out of my chest. I looked around the locker room after the game and saw some of the saddest faces I have ever seen in my life.

That’s just not how I wanted to end my career.

So I talked to other guys on the team. Spoke with Coach Julien after the season a few times, and even Peter Chiarelli, the general manager.

“I know you have one more,” they said. And I felt like I did. More important, I felt like I knew where I fit in with the younger guys in Boston, and knew how I’d be able to help the team, especially if we could make it back to the playoffs.

So I decided to come back.

At the end of the season I got to hold the cup over my head one more time, after a Game 7 win. In my home province.

I guess it could get better, huh. Go figure.

I moved around a lot in my career. I’m grateful to have spent 22 years playing in the NHL. Grateful for all seven of the different teams I played on. Grateful to have ended my last season with a third Stanley Cup in Boston. It was a more storybook ending than I could have possibly imagined for myself growing up.

I’m happy to have met so many great players, coaches, and trainers along the way — just too many people to name, but they all helped make my career special.

Everything was perfect. For 22 years I never felt like the league owed me anything. I was always just a kid who loved to go out and play hockey. Undersized, played inside the dots, decent at hitting people. I wanted to be a guy who always gave everything to help his team win.

To have won three Cups, and now to be so lucky as to be inducted into the Hall of Fame … I never would have imagined there’d be something that I’d remember more fondly than those achievements.

It’s crazy, to be a teenager again and hear myself saying that now, I don’t think I’d believe my words.

But I really do mean it when I say that more important than winning for me, was trying to be a mentor to the younger guys coming into the league.

More than anything, I hope people remember Mark Recchi as a “team guy,” through and through. Because it was such a pleasure for me to spend time with guys like Jordan Staal and Steven Stamkos — still kids when they came into the league. Seeing them come into their own when I was playing alongside them are memories I’ll enjoy as much as any of the championships.

Twenty-two years on the ice and I still have the fever. I still can’t get away from hockey. Of course, it’s different being on the other side of the bench, but coaching satisfies my craving enough that I’m not going to try and make a comeback as a player now at age 49.

Being back in Pittsburgh, where it all began, and being able to witness another young team find success — I can’t tell you how thankful I am to be able to spend so many years doing what I love more than anything in the world.

To everybody who has been a part of my career for 22 seasons. Every fan in Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Montreal, Carolina Tampa Bay, Atlanta, and Boston. Everyone in Kamloops. You are the ones who made my career. Your love of hockey is what gave me so much faith in hockey. You are the reason people love and give so much for this sport.

To have accomplished enough in a career to be accepted into the Hall of Fame —

I will never be able to thank you all enough.

Every day, when I wake up and drive to work, I always think the same thing:

How could it get any better than this?

The answer: It couldn’t.