Letter to My Future Self

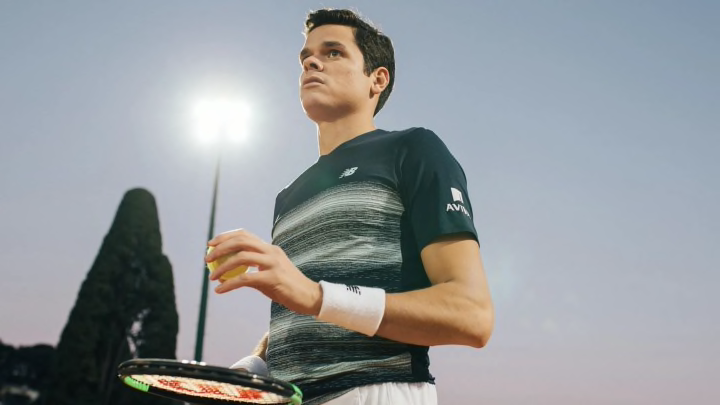

Dear Milos,

I’m sure you’ve forgotten about it by now, but there’s an old Andre Agassi story that I want to remind you of. Andre wasn’t even your favourite player growing up — you were a Sampras guy — but for some reason I’ve been thinking about it a lot lately.

It was early in Andre’s career, late ’80s I think, when he was a prodigy but not yet a superstar. He was still climbing the ladder — he’d just reached No. 3 in the world. He was also still rocking the blonde locks, though that’s beside the point.

A reporter was interviewing Andre after a match. He’d just won and he was walking off the court.

“How does it feel to be No. 3?” the reporter asked.

“I can’t stand mediocrity,” Andre said.

Mediocrity.

That’s what he was feeling. Not grateful. Not relieved — even after a childhood spent being hailed as tennis’s Next Big Thing.

Nope, none of that.

Andre was No. 3 in the world. And what he felt was … mediocre.

Andre was No. 3 in the world — a field that included legends of the sport like Pete and Ivan Lendl.

And it still wasn’t good enough. It wasn’t even close. For a player of Andre’s calibre, there was No. 1 … and there was everyone else. There was the top of the mountain, and then there were the guys who were trying to scale it. Andre knew his goal and he knew that every ranking spot in between where he was and where he wanted to be — whether it was No. 2 or No. 202 — was just that. In between. In the middle. Mediocre.

Crazy, right?

And that’s not even the craziest part.

The craziest part is that, at this point in my life, I can totally relate to what he was going through.

As I write this, I’m 26 years old, and I’m the No. 4 player in the ATP singles rankings. Sounds pretty good, right?

Imagine if I’d told you — back when you were 16 years old and working with a ball machine at a public tennis club in Ontario — that someday you were going to be ranked fourth. You’d have been over the moon. No. 4 — in the world?

More than 10 years ago, I was a kid who got up early before school to train at a club in Richmond Hill. I had signed a letter to attend Virginia on a tennis scholarship. I’d packed up my stuff and was all set to go.

But then … I didn’t. Do you remember why?

I wanted to be a Top 50 ATP player.

Yep, that’s right. Top 50. Sorry — what were you expecting? No. 1? You might be too old to remember this now, but it’s true. You know all of those old Sports Illustrated profiles you would read, where the athlete would say, “From the day I was born, my goal was to be the best in the world” — something like that? Yeah, well, that wasn’t you. You were just a normal kid, Milos. You were just a kid who played high school tennis in Canada, a country that had never produced a men’s finalist in a Grand Slam.

But then you found out, around 16 or 17, that tennis was something you might have a chance to become pretty damn good at. Good enough to go pro, in fact. And when you were picturing it … picturing going pro, as a teenager … picturing what a dream career would be … picturing the kind of career that would be worth giving up on UVA for … well, you pictured the highest ranking you could ever imagine.

Top 50.

That doesn’t mean you weren’t ambitious. You were extremely ambitious — ambitious enough to give up on a sweet deal, at one of the most prestigious universities in the U.S., and ambitious enough to bet everything on yourself by turning pro.

Top 50. That, to you, as 16-year-old Milos, would have been a satisfying life.

And now you’re 26 — and you’re No. 4 in the world.

Which begs the question, I guess: Milos … who are you? Are you an amazing success story, who flew past all of his wildest boyhood dreams by the time you were 21? Or are you what Andre Agassi described himself as, back when he was one place higher in the rankings than you are today? Are you mediocre?

The short answer, of course, is that it’s all a matter of perspective — perspective which hopefully you will gain more and more of, with each passing year.

The long answer … hang on, Milos: Are you too old to remember what FOMO is? You know, the “fear of missing out”?

I’m writing you from 2017 — from a society obsessed with FOMO. Checking out Instagram … scrolling through your friends’ pictures of that Coachella weekend you couldn’t make it to … looking over and seeing “Grand Slam Winner” next to a competitor’s name. We create all these ideas about what’s going on in our lives … about the experiences we are having, or the ones other people are having. And we hang on to these ideas and let them consume us, even when the reality isn’t necessarily that way. Everyone who has ever taken a look at a snapshot of someone else’s life and thought, That looks cool, has suffered from a case of FOMO. And for twentysomethings — just figuring out what they want their lives to be — FOMO can be especially persistent.

I am at a crossroads in my career, having fulfilled my original goals in tennis, while remaining short of the accomplishments of my idols … and I find myself learning to process versions of FOMO in two separate directions.

Sometimes I wonder if, by focusing on my goal, am I letting the world pass me by? Or is achieving my goal, through sheer persistence and drive, worth the sacrifices I have to make?

My biggest phobia at this point in my life is the possibility that someday I’ll look back and feel like I didn’t realize my full potential as a player. That I didn’t get to No. 1. That I didn’t win the multiple Slams.

That I missed out.

You know the ultimate answer to that question, but I don’t.

Not so long ago, I was the kid skipping out on a full ride — and a chance to learn at one of the best business schools in North America — for a crazy dream, a crack at the Top 50.

Every step up the ATP rankings, I learned something new.

I learned that, when I’m training, I respond better to isolation and discomfort.

Remember those two off-seasons in Barcelona in 2011 and 2012 — living by yourself in that 250-square-foot dorm room near the university? You found yourself wanting for nothing. You weren’t surrounded by other players, or coaches, or the constant chatter about rankings. It was just about you and your game and no one was there looking over your shoulder.

You loved Barcelona, even if the late-night culture didn’t fit your training schedule. You’d always be the first to arrive for dinner at a restaurant, which would open at 9 p.m. at the earliest. You’d eat alone, and then walk home, alone, just as everyone else was starting to out into the street to start their night.

You learned so much.

As you went up the ladder, you relied on your strengths. Your athleticism and your serve were your bread and butter. You travelled around the world to train with specific coaches at their academies. You hired John McEnroe to help you compete on Wimbledon’s grass surface, and it helped you get all the way to the 2016 Wimbledon final.

And now you’re No. 4.

You’re so close, but it feels so far — the steps are taller and the spotlight is so much brighter. And it’s making you that much more nervous. Suddenly, the road from No. 4 to No. 1 feels longer than any road you’ve ever taken. You’re struggling to learn how to relax without giving in to the fear of failure. Late last year you hired Richard Krajicek to bolster your attacking game in order to win against the players ranked higher than you.

All these years from now, I hope you haven’t forgotten how much you embraced the climb — from being unranked, to cracking the Top 50, to now.

Even if you never reached No. 1, I have faith that you continued to approach everything as meticulously as you do right now. No matter what you ended up doing after tennis, I hope you found something that channeled your passion and competitive spirit. There’s a quote from Steve Jobs, who I’ve been reading a lot about lately, that I hope you kept with you: “If today were the last day of my life,” he said, “would I want to do what I am about to do today? And whenever the answer has been no for too many days in a row, I know I need to change something.”

Remember how you dreamt of taking internships across all kinds of industries when you retired? I hope you explored that. I hope you went back to school, in an effort to try and refine all of those deep thoughts you were having all the time — if only so they were less messy. I hope you kept exploring: You grew up in a house where there wasn’t a ton of art and music, but in the last 18 months or so, those two fields have really started to inspire you. Spending time with Jeff Elrod in his studio in New York, and listening to John’s wife, the musician Patty Smyth, were two of the best things you did in the past year.

I’ll admit — it pains me to think about how I might feel if I don’t accomplish my goal. But my tennis career is what gave me the means to follow my deepest curiosities without fear of failure or financial ruin. It’s a blessing.

Right now, you are No. 4. I wonder how, in your old age, that makes you feel. I wonder what’s going to happen in the future. I wonder if I’ll climb the last three steps to No. 1. There’s a lot I can’t control. I guess that’s why I’m so meticulous about the things I can — my work ethic, my persistence, my energy.

I don’t know what is going to happen next. I just hope that when you read this, you can tell yourself, “I took every step that I thought was right, in the moment.”

If you can say that, you’ll be content, Milos.

If you did that — all respect to Andre — your life will have been far more than mediocre.

Best,

Milos Raonic

February 2017