I Have Some Things I’d Like to Say

I just want to start this piece by saying how much I love the Champions League.

And, really, don’t we all?

To me, it has always been the greatest tournament in the world. There is something about it, something beyond the trophy and the anthem, that goes back to my childhood.

I think I speak for a lot of people of my generation when I say that those Champions League nights in the early 2000s were so special, especially for kids like me who come from immigrant families.

I mean, I grew up in Gelsenkirchen with Turkish parents, and whenever a Turkish team played in Europe, my family would stop whatever they were doing. They would cheer on the team like their lives depended on it.

I’ll never forget when Galatasaray won the UEFA Cup in 2000. I was nine years old. My whole family are actually Galatasaray fans, except my mum, who is Fenerbahçe! Anyway, we were all watching the final together, and when we beat Arsenal on penalties, my uncle Ilhan, who is six years older than me, actually broke down in tears.

Hahaha! He was crying like a baby!!

That was one of my best childhood memories.

And that was the UEFA Cup, with all due respect.

So can you imagine what the Champions League meant? Can you imagine what it meant to me when I later got to play in it?

Can you imagine what it would mean to me to win it?

There is one game in my career that I still think a lot about. You might remember the Champions League final in 2013. Dortmund vs. Bayern. We were feeling so good. I’d had one of my best seasons ever, and I even scored in that game. It was going to be the cherry on the top for us ... but we lost 2–1.

It felt like a nightmare. Even after the game, I couldn’t understand it. How? Why?

When will I ever get a chance like that again?

To be honest, that final still haunts me. I want that trophy so badly.

But I also fear that if you want something too much, you will never get it.

Thoughts like these can actually keep me up at night. I know I’m supposed to put all these doubts and defeats behind me, but it’s not easy. Of course, I could just tell you that I’m a super confident guy who never has any insecurities. Maybe that would be the normal thing to do, right?

But if I said that, I wouldn’t be honest with you, or with myself.

The truth is, a lot of times I’ll just lie in bed thinking about stuff. My brain refuses to switch off. I’ll think about football, family and life in general. I probably overthink things. But this is the way I am, and I wouldn’t change it even if I could.

In fact, I would like to share some of these thoughts with you here. Because I feel like a lot of people think that we footballers live these perfect lives, like we’re in some kind of happiness bubble that is never disturbed. And that really isn’t the case at all.

I haven’t seen my parents or my brother in more than eight months now. And I haven’t seen the rest of my family in more than a year. My best friends are far away. Part of that is down to the pandemic of course, and I know a lot of people are in similar situations.

But to be completely honest, I have felt a sense of loneliness all my career. It has been like this ever since I left home when I was 18.

As a footballer, I think that feeling is unavoidable.

Obviously, I cannot complain. We are rich and famous, and we get to do what we love. I would never have wished for anything different.

But I still think back to the day I turned professional. It happened quite late for me, and for a long time I didn’t know if it was going to happen. And then my life changed forever.

It’s funny. When you are young, you think that your whole career is going to be a fairy tale.

But there are a lot of things that I wish I knew back then.

I was eight years old when I discovered how brutal this business can be.

I had just achieved the dream of every kid in Gelsenkirchen: I had a place at the Schalke 04 academy. I was so proud. Just wearing the badge felt amazing.

The way it worked was that you played there for a year, and then they would decide whether to keep you or not.

So I thought, Great, at least I’m safe for a year.

But then I began having issues with my ankle. I went to see a doctor, and he told me to stop playing for six months.

At school I had to wear this special sock for my ankle, which meant that I wore one tiny shoe and one massive one. I could hardly even walk, let alone play football.

When the season finished, Schalke let me go.

Or, to put it the way I felt: They grabbed me by the collar and threw me out the door.

It hit me hard. Much later on, I would come to understand it. But at that time it felt as if my dream was over and my career was finished.

Sorry kid, you’re outta here.

Past it at eight years old.

I went back home to play with my friends for a local team. I just wanted to have fun again.

Three years later, my parents got a call. Schalke wanted me back.

I said, “Tell them no. I’m not going.”

The pain was still too raw.

I think my parents kind of understood me — but not really. This was another crack at my dream, so why was I refusing to take it? But Schalke had been my first rejection, and it really hurt.

And anyway, my parents had never pushed me to go to Schalke. They just wanted me to do well at school. Like really wanted me to do well.

I still have nightmares about school.

I’m not joking. I can wake up in a cold sweat from thinking about old exam papers.

Let me explain something to you. My parents grew up in Turkey, and in Turkish culture, there is huge respect for your elders. Neither of my parents had finished school. My mum was a cook in a swimming-hall restaurant, and my father was a truck driver for a beer company. They had never had the education to get high-paying jobs.

So when my brother and I started school, they wanted to make sure we made the most of it. Which, at the start, I did.

But as I began to spend more time on football, my grades got worse. I had to really fight to get a degree. The fear of failing my exams hung over me like a dark cloud.

Can you imagine what my parents would have said if I failed? Can you imagine their disappointment??

That is why I still have nightmares about those exams.

Twelve years on, they still haunt me.

To be clear, my parents did a great job raising me and my brother, Ilker. But I was studying so much that I hardly had time for anything else. My life was just school and training. When my friends went out on a Friday night, I’d stay at home because I had a game the next day.

I missed out on a lot. I kind of feel like I sacrificed my youth.

And the crazy thing is that I didn’t even know if I was gonna turn professional. A lot of kids are like, “Oh, I’m gonna become a footballer.” But I never had that laser focus. I had exams to pass. And to me, football was still supposed to be fun.

The first time I seriously thought about turning pro, I was 17. I was with the Bochum first team on a preseason camp, which was the first time I had joined a professional team for an extended period. I played in two friendly games, and I scored in one and assisted in the other. I was like, Huh, I could do something here.

About six months later, the day arrived: I left home to sign a professional contract with Nürnberg.

And then came all those things that I had never really thought about.

The first thing you realise is that you have to leave your family and friends. Imagine this kid who has spent his whole life in the same city, close to his parents and brother and cousins, and now he has to travel 450 kilometres away to live on his own. He gets really lonely. Then he has to make the step up to senior football, which is just a completely different world from youth football. He gets injured after two weeks. Then he gets frustrated with the older players, because they are simply wrong about many things — but his Turkish upbringing has told him not to disrespect his elders, so he stays quiet.

That was me at Nürnberg. It was a total shock to the system.

Back then I actually remember being grateful that Schalke had rejected me. I had already faced this huge disappointment, so I was kind of prepared for another struggle. In the end, that’s what helped me break through at Nürnberg and have two successful seasons there.

The longer you go in life before suffering a setback, I think, the harder it is to handle.

Imagine this kid who has spent his whole life in the same city, close to his parents and brother and cousins, and now he has to travel 450 kilometres away to live on his own.

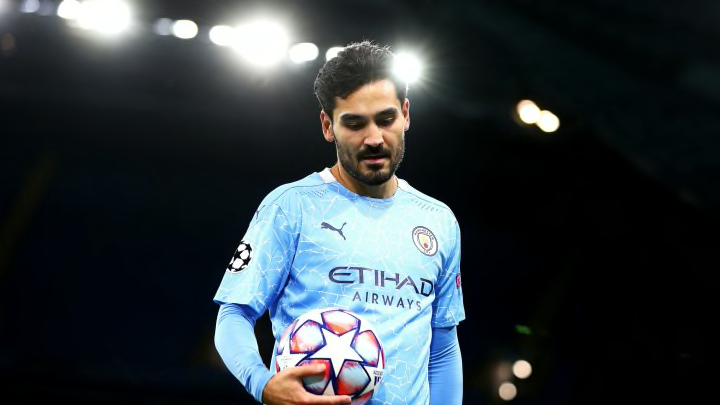

- Ilkay Gündoğan

When I arrived at Dortmund, I thought I was prepared for anything. I was wrong. I’ll never forget what happened. I was looking for an apartment in the city, and I overheard these people talking about me.

They would say, “Have you seen his name? Gündoğan. That’s Turkish. Do you really think he can afford it?”

I mean … what the f***.

Where do you even start with that?

Of course, once I told them that I was a footballer, their tone changed completely. Oh sir, please come in, have a look. Anything we can do to help, let us know.

And these people were immigrants themselves!!

It was just so sad.

The really bad thing about stuff like this is that it’s so hard to shake off. The insecurity stays with you. You feel that people are looking down on you, even though they might not be.

Honestly, I’ve had people telling me that they are surprised how good my German is. I’m like, “Well, I grew up in Germany. It would be a shame if I didn’t speak the language.”

The same thing has also happened the other way. My parents are Turkish. I consider myself Turkish, too.

But some Turkish people are like, “Oh, you’re Turkish??”

It’s a really bad feeling. I belong to both countries, but sometimes it feels like I’m sort of caught in between them.

They say I’m not fully German.

They say I’m not fully Turkish.

So what am I then?

The worst part was when I had to decide whether to play for Germany or Turkey. I was still in my late teens, so I didn’t know whether I would someday become a big player. I could never imagine the kind of reactions that my decision would lead to.

Especially in Turkey, they question how Turkish I really am. And that is just so annoying.

Just because I play for Germany, that does not make me not Turkish, you know?

But it seems like this is very difficult for some people to understand.

Thankfully the critics are mostly online. When I go to Turkey, the people I meet are always proud of what I have done, especially in my grandparents’ hometown. I also feel richer for understanding two such great cultures, and I think it helps me understand other people, no matter where they are from.

But the whole thing also shows you what fame can bring along.

When you play football, every decision you make is always magnified.

Funnily enough, my job at Dortmund was to replace another player with Turkish roots. You know Nuri Şahin? Well, Dortmund had just won the league, he had been the Bundesliga player of the year, and then he had gone to Real Madrid. I was his replacement.

No pressure, kid!

After three months, I was not even in the match-day squad.

We were about to play Wolfsburg, and I remember Jürgen Klopp took me aside after training and told me I hadn’t made the cut.

I didn’t say anything back. I just shook my head.

That was my way. I’m not this guy who thinks, I’m the best, I should always play. I always think that what I’m doing isn’t good enough, and that there are others who are better than me. So now that people had begun to question me, I did the same.

And then my teammates beat Wolfsburg 5–1 without me.

Was I even good enough to play for this club?

Thankfully, I was used to setbacks by now. I knew I just had to keep working.

A few months later, against Hannover, one of our players got injured after eight minutes, and Jürgen subbed me on. I didn’t even have time to warm up, but I played well enough to keep my place.

Then I scored the winner in the German Cup semifinal.

We won the final.

We won the Bundesliga.

I was playing every game.

If you really struggle to achieve something, it usually ends up being worth it.

But then you have to keep going, and that takes a lot of discipline. As a footballer, 99% of your life is planned. Every day you get a message on your phone telling you where to be and what to do. You can’t just wake up and decide to go for a coffee.

Any tiny error can put you in big trouble.

I know, because I once managed to make Jürgen Klopp angry.

Like, really angry.

It was in my second season at Dortmund. We were trailing in the Bundesliga, but we had a shot at the Champions League. The staff had this rule that if you felt bad before a training session, you had to report it to the team doctor. That way we would avoid injuries, and Jürgen would know that you might not be able to train.

So one morning I woke up and felt my hamstring a bit. Did I have a muscle problem, or was I just tired? I couldn’t tell.

I probably should have texted the doctor.

But I thought, It’s probably gonna be alright.

Like always, I came to the training ground an hour before the session started. And just to be sure, I asked the doctor to take a look at my hamstring.

He said, “The muscle feels a bit tight. Why didn’t you text us?”

I said, “Don’t worry, I can train. It’s not a problem.”

He said, “I have to let the boss know. We can’t take any risks.”

I waited a few minutes, and then Jürgen came in. He was not happy.

He said, “What’s going on?”

I said, “I just feel my hamstring a bit, but it’s O.K. I can train.”

He said, “Why didn’t you text us? You know about the rule.”

I said, “Yeah, but I’m fine, honestly.”

I was trying to find a way out of it, even though I knew I was wrong. Jürgen kept saying that we couldn’t take any risks. I kept saying that I could train.

And then he snapped. You know when he gets these intense eyes and grits his teeth? He gave me that look and shouted, “DO WHATEVER THE F*** YOU WANT TO DO!”

Then he slammed the door behind him.

And I was also angry at that point!! I’m usually very nice and calm, but the whole argument had me fired up. I was like, “Why is he reacting like this? What’s his problem?”

I told the doctor I would do the warmup and see how I felt.

“DO WHATEVER THE F*** YOU WANT TO DO!”

- Jürgen Klopp

About half an hour later, I put my boots on and walked onto the pitch. Jürgen came up next to me. I was expecting a lecture, but he put his arm around me.

He said, “My friend, do you know why I was so angry?”

I said nothing….

He said, “I just care about you. And I don’t want you to get injured.”

Then he gave me a big hug.

I was shocked. We had had this fight, and now he was talking to me the way a father might talk to his son. That showed me what kind of person he is: very emotional, of course, but also very open and honest.

Jürgen taught me a lesson that day: Always try to be honest. Both with others and yourself.

A few years later I had to put that into practice. By 2016 I had been at Dortmund for nearly five years, and I felt stuck. I needed a new challenge.

I could have waited out my contract, but that’s not who I am.

I knew that I had to change something.

And then in February, Pep Guardiola said he would leave Bayern Munich to take charge of Manchester City. And I just couldn’t help it. I thought, Imagine what it would be like to play for Pep.

I had loved his Barcelona team, which was for me the best club side ever. And every time I had played against Bayern, it had been so hard. You spend 90 minutes chasing the ball, and you don’t understand why. It’s like there’s a matrix there that you cannot see.

I had heard from a couple of people that Pep liked me as a player.

Also, this one time we had played against Bayern, I had been standing with some teammates in the tunnel just before the second half was about to start. Pep appeared, and as he walked past us, he nudged me.

I was just like, What the hell was that?

It was a casual thing, but why? To this day I’m not sure. Maybe I should ask him. But surely you would only do that if you liked someone a little bit, right?

Even when it became clear that City were going to sign me, I wanted to be assured about this. I remember going to meet Pep for the first time, just before I signed, and I had this question that I wanted to ask him.

I could have asked him about tactics, or about all the times we had faced each other. I could have asked him about the great plans he had for City.

But as we sat down, I just had this one question.

I think I just blurted it out.

I said, “Do you really want me?”

Like really really?

Of course I knew the answer. Why would he meet me in person if he didn’t want me?? But I just wanted to know. I needed to hear him say it.

Pep and I have been working together for five years now, and we have a very good understanding. Even when I ruptured my cruciate ligament in December 2016 and was out for eight months, he had no doubt that I would recover my best form.

I remember one time, I was hanging out with a friend of mine when we remembered that it was Pep’s birthday. So my friend suggested that we give him a present. Pep is actually my neighbour here in Manchester, so we bought a bottle of champagne, my friend wrote him a card in Spanish, and then he went to knock on his door. When he came back, he said that Pep had been very happy about it.

Anyway, I went back to the cinema room and kind of forgot about it. About half an hour later, there was a knock on the door. I was like, “Who the f*** is this?” I thought my friend had ordered pizza or something.

My friend opened the door, and it was Pep!

He said, “Where’s Gundo?” (He calls me Gundo.)

We were both really surprised, because Pep is such a private guy. We had seen him around in the elevator and stuff, but he had never been in my apartment. He had brought the champagne bottle and three glasses. He ended up staying for an hour or so, just to chill.

It reminded me that, even though we play football, this profession is also about humans, you know? And I think that, when I end my career, what I will remember the most are the people I shared it with.

I guess you could say the same thing about life.

No matter what happens with the Champions League, I will be very happy with my career. Just making it as a footballer is a dream in itself, really. I still remember the day it happened to me. I’m 18, and I’m sitting in the schoolyard with my friends during lunch break. I spot a car that is pulling up outside the school, and I think, I know that car from somewhere.

It belongs to my uncle Ilhan. But what the f*** is he doing here?

Then he walks up to me and says, “Pack your stuff.”

I say, “Why?”

He says, “You’re going to Nürnberg tomorrow. They have offered you a contract.”

And I can’t believe it. I’m so excited. I ask him if it’s really true, and it is, and no he’s not joking. We go inside to tell the headmaster that I’m leaving school.

This is really happening.

The next day we wake up at 5 a.m. to drive to Nuremberg. I say goodbye to my parents. I’m leaving home. I will be gone forever, but I don’t know that yet.

All I can think is, This is going to be amazing.

I’m just glad I turned out to be right.