The Life of “Dadado”

Para ler em Português, clique aqui.

When I think about the World Cup, the first thing that comes to my mind is paint.

Little tin cans of paint, in blues and greens and yellows.

The brightest colors you could imagine.

In Brazil, there’s this tradition every four years before the tournament starts. You go out and you paint the streets of your town. It’s sort of a competition to see who ends up with the most beautiful murals and pavements. So, for the 1982 World Cup, just like every other kid in my country, I went out and painted my street with the other children who lived beside me. Everyone in our town would take part, and then murals were everywhere … in all kinds of colors and designs — birds, the Brazilian flag, players on the national team.

After we were done painting, there was an old neighbor of ours, Mr. Renato, who’d have everyone over to watch the matches. I can’t remember much about him … other than he just seemed so big to me when I was that little. He was retired from the Air Force, or something like that, and he’d buy us all these french fries and soda. Now that was a big deal. We’d didn’t get to have that kind of food a lot. It’s something so small like that that just makes a memory special in your mind … fries and soda … sitting with your friends in front of the TV watching football, thinking maybe … one day … that could be you … a professional footballer.

I grew up in Bento Ribeiro, which is a northern suburb of Rio de Janeiro. It’s lower middle class. There’s no slums or anything like that, or piles of houses that you’re always seeing on TV. It was just … home. And there wasn’t a day where football wasn’t the topic on everyone’s mind

And honestly, by the time I was five years old, I already saw my life around football. I don’t know how to explain it, but I just connected with the sport right away. It was just there … inside me. It feels so easy to say that when you’re young. I want to be a footballer. But as a kid, you don’t really know what that means. You don’t really grasp the hugeness of that. Reality is not something you could comprehend when you’re little and just dreaming.

And I definitely didn’t know what that meant yet when I was just five years old … as I dipped my brush into a can of paint. I didn’t know where football was about to take me … as the blue dripped down my wrist and arms, as I stood there with my friends on our street. While a new portrait of Zico watched over us.

I didn’t know how fast it would all go. How quickly a dream would become … life.

For right then, I was still just one of the other little boys in our town known for playing football.

And I mean playing all the time.

Maybe, looking back, that’s what made me different from all the other kids in Brazil who wanted to be footballers. I wasn’t just dreaming of being the greatest, but actually, truly believing it. That I really could be … one of the best who ever played.

I laugh thinking about it, because I don’t know where it came from, or where that thinking started.

It was just … life … from the moment I first kicked a ball.

But, to be honest, I don’t even remember the first Flamengo match I went to with my father at Maracanã. It’s weird, but the only thing I can compare it to is that it’s sort of like walking, you know? Of course there was a time when you couldn’t or didn’t walk, but you don’t know life without it. And I just don’t know my life without football.

Even my first nickname came from a time I can’t remember.

Whenever I scored a goal against my two older brothers, they’d scream, “Dadadooooooo!”

When I was little, I had trouble pronouncing Ronaldo. It always came out sounding a little more like “Dadado”… so … Dadado it was.

When my brothers would go inside the house, I’d stay out with my ball, just kicking and kicking. Left foot, right foot, left foot. I loved playing out there in our yard. We didn’t have a very big house and I’d sleep on the couch most of the time. But the good thing was that the house sat on all of this land. And that’s all I needed: Space to play football. Being that it was in Brazil, our home was surrounded with all of these fruit trees … guavas … mangoes … jabuticabas. So I would dribble through the trees when my brothers left me.

While I was out there I’d be thinking to myself, I’m going to be the greatest football player ever.

I looked at every opportunity as a step toward becoming a professional football player. It was like a menace in my head. I couldn’t think of anything else — as much as my parents wanted me to focus on school. And after that first year playing futsal, all the other steps seemed to fall into place. Part of it was luck … a lot of it was dedication. I began training the next year with São Cristóvão football club. And by the time I was 13, clubs were already looking at me. So I went to Belo Horizonte to play for Cruzeiro. When I was 15, I got my first invite to train with the national team. When I was 16, I made my professional debut for Cruzeiro.

And the next year, in 1994, I went to my first World Cup with Brazil.

Like I said, it all happened so fast.

And as much as I wanted all of it, every moment still felt like a surprise, in a way. I didn’t know what a timeline for becoming a professional was supposed to be like. There’s no plan or handbook. Sometimes it felt like I went from one day playing at school and in our backyard, to practicing with Bebeto.

Then the World Cup came. How can I describe that 1994 World Cup? Or that team?

Let me put it this way. Harvard’s a pretty big deal in America, right? Well, playing with that team in that tournament was like going to the Ivy League of football. It was a first-class, front-row education on how to not just play football, but how to be a footballer. How to be a World Cup champion.

I didn’t play a minute in that tournament, but I watched and absorbed everything that I could. I took notes, collected all this information, knowing that someday I was going to be back.

That summer changed my life and my career.

Because that’s also when I first met Romário. He was obviously someone who I grew up watching as a striker, and between him and Zico, I just thought, That’s what a player looks like, on and off the field. When I got to camp that summer, Romário was always so attentive to the younger players … especially me. Maybe because we were both strikers, or he saw in me the same dedication and drive, I don’t know. But there’d be so many times after practice that we’d just talk. It was weird, but I felt like he saw the sport like I did: That it could be this evolution, a series of steps that you’d take until you could make the next one. And the next one. Until you were the best of the best.

And the next step, he told me, had to be Europe.

Romário had already joined Barcelona at that point and had played for PSV, who was talking to me about coming over. This may sound funny, but one of the things we spoke about was the weather. What was it like going from playing in Brazil to pitches in the Netherlands covered in snow?

The biggest adjustment though, would be the competition. He’d tell me about winning La Liga, or playing in a Champions League final. And then I knew as well … if I wanted to actually be the best, I needed to follow that path as well. So I signed with PSV.

George Weah.

Marco van Basten.

Paolo Maldini.

Those were the guys who I looked up to as a kid. The greatest ever. And now I was playing in Europe, too. I needed to stand out as well. So … I became bold, let’s say. I set targets and I went out to achieve them. And I made sure people knew what I was doing as well.

When I got to PSV, I said I’d score 30 goals in my first season.

Then I scored 30.

Then I said I’d be the best in the world.

Then I went to Barcelona and won the Ballon d’Or.

I had always had that confidence in myself as a kid. But announcing the goals, the awards? I was just doing what I had seen other guys doing when I was growing up. The bragging … the showmanship … it took me a couple of years — probably longer than it should have — to realize, This isn’t me. It wasn’t my personality to be the type of player who spoke like that. At the end of the day, I could just let my game do the talking.

My drive didn’t go away, of course. I kept giving myself those challenges. But I kept them to myself. Being the best didn’t need to be about headlines. Being the best was always just how I wanted to play the sport. Constantly pushing myself. Constantly finding my limit … and going past it.

What I was doing by saying these things was testing my own limits.

Except the one thing that I still did not do was to play in a World Cup.

In my mind, it was only a matter of time. And I had plenty of time.

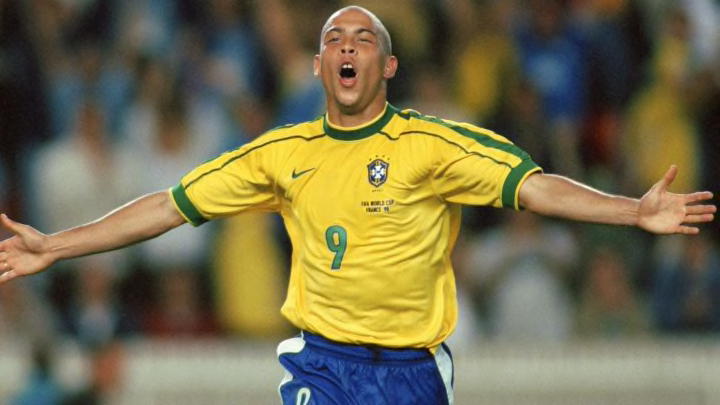

At World Cup ’98, I was 21 years old and football was just fun to me. I scored four goals on the way to the final against France. And then, on the day of the final, something happened that I cannot explain. I became very, very sick and I had a seizure in my bed. I do not remember much of it. But when the doctors did their tests and cleared me to play, I played. Of course, I did not play well and we lost the match 3–0.

It was a devastating time. But, in my mind, I was still young, and there would be many more World Cups. There would be many more opportunities.

Of course, this is not how life really works, is it?

The following year, I had a very bad knee injury. It was so bad that some people said I would never play football again. Some people said that I would never even be able to walk again.

And then my limits were truly tested.

I have to be honest and say that there are things in football that always bothered me. The traveling. The waiting. But those moments on the field … just … playing? I loved it so much. That emotion never lessened for me. At PSV, or Barcelona, or Inter — I always felt the same happiness as I did when I was little boy.

Life, for me, felt like it started and ended on a football pitch. So when my knee was destroyed, it was like my life had been taken away.

So I did whatever I could to make sure I’d get back. I traveled to the U.S. to meet with doctors and surgeons. I went around the world. It went on like this for three years of rehab and setbacks. I knew the 2002 World Cup was coming, but it wasn’t trophies or goals that motivated me. I just thought about that feeling — that feeling that I can only find on a football pitch with a ball at my feet.

Three years after my worst injury, and four years after losing the final in 1998, I had the ball at my feet in South Korea, playing in the World Cup for Brazil.

And right before the final against Germany, something amazing happened.

When we got in the changing room before the match, our manager, Luiz Felipe Scolari, had something to show us on the television. We kind of looked around at each other, not sure what was going to happen. A TV in the changing room was not a normal thing.

“Sit down,” Luiz told us. “There’s something I want you to see.”

He turned on the TV and hit play. It was a recording from Globo, a Brazilian channel. We hadn’t gotten to see the news from our country since we were playing in Japan, so it was the first time we’d seen or heard from the people back home.

But this wasn’t just a regular broadcast. In the show, they went to each of our hometowns, to show how the neighborhoods and states were celebrating. Eventually they got to Bento Ribeiro … and right there in front of me … I saw the streets I grew up playing on … I saw the walls I’d kick my ball against.

And I saw little kids standing by the colorful murals that they had painted for us, just like I used to do.

It was the last thing we saw before we went out onto the field.

So when it was still 0–0 at half time, there wasn’t a worry within our team. I will tell you the truth … there wasn’t a lot of conversation, or any big strategy being discussed in the changing room. We just knew what we needed to do. We just accepted it. We just knew we’d score the goals we needed. And we’d win.

There was just this … confidence.

We felt it throughout the tournament: Every game was ours. We didn’t have to say how great we could be. We all just felt it. That team was probably the best team I ever played with.

And for me, I don’t know, but the higher the pressure, the easier things become. I could see things. I was calm. I could just … breathe. I think that’s what makes a good striker: having all of this emotion, but knowing how to control it.

Then when you do score … it’s almost like an orgasm … but more.

So when I scored twice to put us ahead of Germany, I thought, This is it. Everything was right there … a World Cup trophy, minutes away from being ours … I had never felt anything like that on a pitch.

And then at the 90th minute, I was subbed off. It was the most incredible thing — what Luiz did for me — because I could see everything. I could take in the moment of what we had just done. As I walked off the pitch, I thought about the people who’d said I’d never be back. That I’d never play again. That I might never even be able to walk again.

This was 2002, and people were just getting cellphones. So when I looked around the stadium, I saw all these little white squares, like a disco. It took me a minute to realize what was happening. People had their flip phones pointed at me and they were taking pictures.

Back then, this was a new concept.

And then, when I got to the sideline, I saw Rodrigo Paiva, the press secretary for the national team. This man had been with me at every point in my recovery. He used to walk slowly beside me when all I could do was walk. I just lost it and started crying. All of this emotion, I had never felt anything like it before.

That moment … it was a gift.

Then, of course, we celebrated. I don’t think we slept that night. It was just one big party until we flew home to Brazil. And on the flight home, I sat with my son — who was two years old at the time — in my lap and I looked over at my father. We didn’t really say anything to one another. We never really had to … that was just our kind of relationship. But we both knew what that World Cup meant. What it meant for our family. What it meant for Brazil.

And what it meant for Bento Ribeiro.

The plane stopped in many different Brazilian cities on the way back. Those were some of the best days of my life. Seeing all the people in our country, and all the happiness. Seeing murals everywhere. But now … with our faces on them.

After winning that World Cup, though, I looked toward the next steps … the next targets … the next challenges in my career on the field. Except, it all became a lot harder after my injuries. I still think about where I would be if those knee injuries hadn’t happened — if I knew how to train properly.

For me, football was always about seeing how far I could push myself and I feel I did that for as long as I could. I had made it through another knee injury and I joined Corinthians. But when other health problems made it difficult to not only play, but also to breathe, and stand up, and walk … I knew I had to stop. If I couldn’t be the player that I wanted to be on the pitch, if I couldn’t have the same feeling, then I couldn’t be out there at all.

In 2011, I needed to make a decision.

I knew that I needed to say goodbye to football.

At least, to my time on the pitch.

But football — it’s like an addiction. For players. For fans. For everyone. It’s why it just grabs so many people all over the world. So I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about that since I’ve stopped playing. I think about what the sport gave to me.

I want to make sure that kids growing up now — wherever they may be — see football the same way I did. But cities and towns are changing. When I was growing up, there were football pitches everywhere. Now, there are buildings and other developments taking over a lot of those spaces, so you’re not seeing kids out on the streets as much playing or kicking around.

To me, a football pitch is the most perfect thing in the world. It can be in a stadium, or on a beach, or on just a big patch of grass with fruit trees. It doesn’t matter. When you are a kid, you can look out on a pitch and see your future.

One of the things that makes me happiest in life is when I hear guys like Messi, Neymar, Cristiano Ronaldo or Ibrahimović say what an influence I had on the game, on how they play, on their memories and dreams of growing up and wanting to be footballers. Think about this … I was just a boy in Brazil painting murals and dreaming of being like Zico. They were just boys in Brazil and Argentina and Portugal and Sweden dreaming of being like me. We were connected by this feeling, you know?

That is beautiful to me. That is football to me.

You know, I thought a lot about how to finish this. I am good at starting to tell stories, but I never want to finish them.

I will finish by saying this: I lived my dreams. How many people can say that about their lives? To have seen and lived in so much color.